They may be poles apart ideologically, but for TOP and the New Conservatives, the election campaign featured some remarkably similar successes and failures for both.

On an ideological level, it doesn’t make sense to put The Opportunities Party (TOP) and the New Conservatives in the same category. But their electoral vote share around 1.5% isn’t the only thing they had in common this election.

Both pivoted heavily to online campaigning, in part because they struggled to gain traction in traditional media. Both spent much of the campaign talking about issues they believed weren’t getting enough attention. Both failed to get into the TVNZ minor party debate, despite polling not too far away from three parties that were granted access.

And both say that this election has laid a platform to come back stronger in 2023, even with the traditional struggles minor parties have in breaking through. While their actual vote share wasn’t as good as when the parties operated seemingly as vanity projects for millionaires (Colin Craig in 2014 and Gareth Morgan in 2017 respectively), 2020 provided a chance for the party organisations to mature into something more broad-based and driven by members.

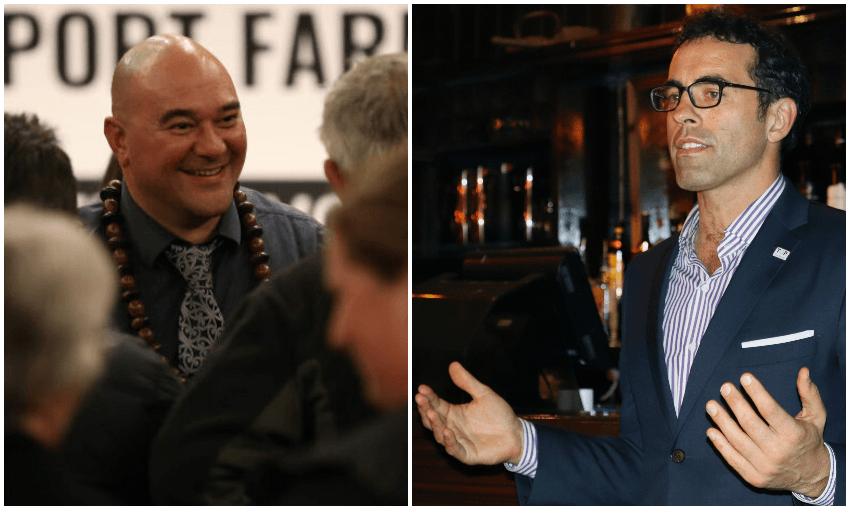

New Conservative deputy leader Elliot Ikilei has spent the year working full time on the campaign, and has a while left on his contract with the party. He said he misses the community work he did before politics, but an issue that came up during the campaign gives a steer on what he might end up doing next.

“It has to do with the yawning hole in our media and ideological spectrum,” he said, suggesting that in his view, the New Conservatives struggled to get a fair hearing in traditional media. “I’m trying to word it in a way that doesn’t sound like I’m just whinging, but I think what we saw was an excellent example of a population who were very intelligently motivated by fear and a partisan media.

“When you have wall-to-wall coverage of one party, and a fear of Covid being, I think, excellently played, I think it was a relationship of happenstance and opportunity. Newspapers have to make money, and political parties have to capitalise on any opportunity to gain more airtime. And I think what we saw was a convergence of that.”

Some criticised the New Conservatives for presenting a message that was simply too extreme for potential voters to get behind. Ikilei doesn’t see it like that. “The way that we were narrated, it would have been [too extreme],” said Ikilei, bringing up a previous controversy around how the party’s te reo in schools policy was presented, which he believed was misleading.

TOP also had difficulties getting their message out to voters. It ran very hard on housing issues and its universal basic income policy. But by the end of a campaign in which those issues barely featured, TOP was reduced to holding stunts to try and get cut-through, like crashing an open home for a supposedly affordable house in South Auckland.

TOP’s message was built around the contention that change was necessary and that its policies would allow the country to successfully implement and navigate those changes. But as party leader Geoff Simmons admits, that message misread the mood of the country after a year of upheaval from Covid.

“Obviously Covid prompted a pretty big rethink on our strategy, and even ‘Don’t leave change to chance’ [their election slogan] was a step back from ‘Vote different’ [the slogan they rebranded with in 2019]. A lot of the stuff we were coming out with in March was very bold and in your face, and we ended up softening that,” said Simmons.

“There was a debate to switch tack entirely and go down a line of ‘the voice of reason’, which in hindsight may have ended up being a better bet. The longer the election campaign went on, the crazier it got, so that might have been a useful distinguishing point. But this is the thing with having basically a volunteer organisation – you can’t pivot and get all your branding changed overnight as much as you might like to. We had to make the call in the midst of that Covid lockdown about what direction we were going to go in.”

In contrast, the messaging of the New Conservatives was relatively scattered. While the party had billboards all over the country, having about a dozen different slogans painted across them didn’t necessarily tell voters what the most important priorities for the party would be.

Ikilei said that if the party was better known, that strategy could’ve been more successful. “The question was do we run on the old three-hitter that most political parties do, three basic policies and get them out there; whereas we had quite a few. It depends. In hindsight, yes, but only with the retrospect that oxygen was starved to most parties.”

Both the New Conservatives and TOP made the most of digital campaigning, but at times, it almost looked like supporters of both had convinced themselves the reaction they were getting on social media was reflective of a wider swing, rather than being an echo chamber. Some prominent online supporters of New Conservatives were convinced the party was really polling above 5%, and it just wasn’t being reported.

For Simmons, the key point of online campaigning was that it brought people in to create a stronger ground game for 2023, and that momentum needs to be capitalised on. “Over the past two months, we’ve had so many people offering to volunteer, more people offering to volunteer than we’ve had the capacity to deal with, because everyone’s been trying to run a fucking election campaign. And bringing on new volunteers is a really time-heavy thing.” He said the most common types of volunteers approaching TOP were policy heads, and IT people, which lent itself well to digital campaigning, but they needed to make more of other approaches.

In terms of polling, the New Conservatives made painfully slow progress over the last two years, moving from regularly scoring under 1% to regularly being between 1%-2%. These margins don’t sound like much, but it’s not a long way up until cracking the 5% threshold looks viable. TOP, by contrast, looked dead and buried in the middle of the year, regularly polling at basically zero. What changed to start pushing them up?

“That’s when we started our campaign, basically,” said Simmons. “We held it out until six weeks out from the election – that’s what we decided to do. And that is one of the lessons to us in 2023, that we need to start a bit earlier than that. This time around, in between Covid and our resources, that was what we decided to do.” A pre-campaign advertising blast in March ended up being totally eclipsed by events.

The fact that both parties are talking openly about 2023 is interesting because parties that fail to win seats in elections often struggle to make it to the next one. TOP, in particular, had huge difficulties coming out of the turbulence of Gareth Morgan’s exit and the in-fighting that created. At the end of last year, Simmons was speculating about whether it would even be worthwhile sticking around to fight this election campaign unless polling improved rapidly at the start of 2020. “That was a pretty massive distraction, particularly at a time when we were already quite a bit behind,” said Simmons.

Ikilei said the New Conservatives were up for having another go in 2023. “Our structure is strong. The policies are super strong. The ability to actually expose things that are being hidden by the government, we’ve got that … People on the ground have been told fierce messages of determination – don’t you give up. We’ve been inundated with those sorts of messages.”

“What’s not good is actually outside of our current control. So what I think we might start looking at is how can we go to that core issue, and allow or support something that might be put in place to grow. And the big one, of course, is oxygen. When we get our stuff in front of people, they love it. Or a few absolutely hate it.”

At TOP, there’s likely to be change which could potentially include a change in its leadership which Simmons says he’s comfortable with. “I really want what’s best for the party. There’s not a lot of ego tied up in this issue for me.”

“Some people seem to think I’m indispensable to the party, but by the same token, there are a lot of people who say TOP’s not able to connect with voters, and still comes across as too wonky. And I’m like ‘that’s me, I’m a wonk’. That’s a pretty big question that we have to contemplate over the next couple of weeks.”

Is the party disheartened by its vote share going down from 2017? Simmons admits “2% would’ve been nice”, but he points out they had only a fraction of the budget it had in 2017. “TOP really has transitioned to a movement now. All of the candidates are chafing at the bit; for almost all of them it was their first run out and they all feel like they’ve learned so much and are keen to keep going.”

If both parties are able to hang on, there’s likely to be no shortage of issues to get stuck into. The problems TOP has been campaigning on, particularly the increasing unaffordability of housing, appear to have become more deeply entrenched over the current government’s last term. And for the New Conservatives, the parliament that’s been elected potentially leans much more socially liberal than the last one, which could open up more space for social conservatives to campaign.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for both will be about figuring out how to translate their passion into pragmatism. Their support bases are made up of people with deep convictions, and as the New Conservatives were fond of saying throughout the campaign, none of its candidates are professional politicians. But if either party wants to breakthrough next time around, it may have to learn how to be just that.