Covid-19 vaccination won’t be enough to save us from hard choices that will need to be made during our second or even third year of living with the coronavirus.

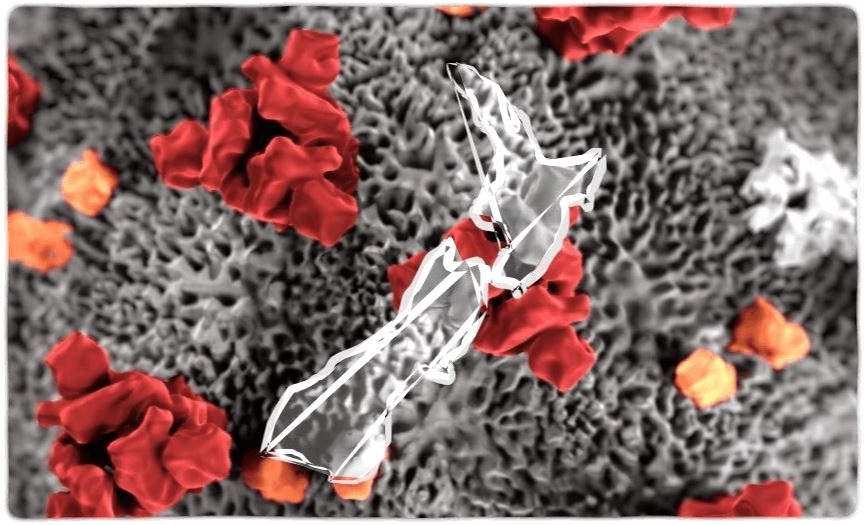

Keeping Covid-19 mostly out of New Zealand has been a Herculean feat, drawing praise from around the world. Over the next year, Aotearoa will face another daunting challenge: whether to willingly let the virus back in.

Sunday marks the anniversary of New Zealand’s first confirmed case of what was then a largely unknown coronavirus. In the year since, Covid-19 has killed more than two million people around the world, infected millions more and radically reshaped the global order for years to come.

As the virus turns one, there is cause for optimism. Vaccine developments have shattered expectations and one country, Israel, has already inoculated over half its population. While lockdowns continue among mature democracies and dictatorships around the world, infection and death rates are slowly receding.

As New Zealand approaches this unwelcome birthday, The Spinoff looked to the future and asked experts what the country might look like a year from Sunday, at Covid-19’s second anniversary. Their musings point to some of the debates the country will face over the coming year.

The year of the vaccine

The progress of the world’s vaccination programmes, along with the appearance of new mutations of Covid-19, will continue to dominate headlines in 2021. However, vaccines alone won’t bring about a swift end to the coronavirus, warns Covid-19 response minister Chris Hipkins.

“We’ll never wake up and find ourselves in a world like it was two years ago … there’s no big bang and the world goes back how it was,” he told The Spinoff this week. “Vaccines are going to make a big difference but exactly what kind of difference they make has yet to be determined.”

The vaccines have been proven overwhelmingly effective in preventing severe disease and hospitalisations, but one piece of outstanding research is to what degree the vaccines will stop people from transmitting the virus to others. It is likely the vaccines will stop onwards transmission quite reliably, as vaccines for other viruses do.

Hipkins’s best-case scenario sees, in early 2022, a world not radically different from where we are now. “A series of ongoing incremental changes”, he says, mean we worry less on a daily basis about a virus that is still very much around. Managed isolation and quarantine facilities are still operating at the country’s border, but they’re better at catching the coronavirus. There’s some international travel into the country, and maybe some of it’s Covid-free, but exactly how much is still unknown.

“Covid-19 isn’t about to suddenly disappear from the planet because vaccines are more broadly rolled out. It’ll still be out there and we’ll need to respond to it from time to time, but life will start to look more normal,” he said.

In recent weeks Hipkins has made a habit of under-promising and over-delivering. His prognosis for the next year seems to reflect that caution. For him personally, that means giving more of his energy back to some of his other ministerial portfolios instead of the near-daily 1pm stand-ups. Notably, Hipkins is still the minister of education. “I didn’t get into politics to be the minister for a virus,” he said.

His worst-case scenario is seeing little improvement in the year ahead.

According to data released last week by the health ministry, 69% of New Zealanders are willing to get a “well-tested and approved” Covid-19 vaccine. Health officials say they hope to convince about 10% more to get the jab, especially among Pasifika and Māori who have less confidence in the vaccine. Hipkins says he’ll aim for an even higher number.

It’s likely that by the end of February 2022, most – if not all – of the 80% of New Zealanders that health officials expect will want a jab will have had one. At that point, when four out of five people are vaccinated against Covid-19, the question will be what to do about restrictions at the border. Tourism operators and education providers will be clamouring for fortress New Zealand to open up and they could find sympathy from a population that’s largely immune to a virus that could remain with us forever.

Hipkins says caution might still be required next year. “When it comes to reopening to the world it’s likely to be a progressive set of changes, starting with the lowest risk countries first and vaccination may play a role in some of those decisions,” he said, warning against looking too much into a “crystal ball”.

While the minister is reluctant to talk about whether the government might begin to accept more risk later this year or in the next, the current policy is one of the world’s toughest, he said proudly. “Our tolerance for risk is the lowest in the world when it comes to MIQ. Other countries might be willing to tolerate a 5% risk at the border … We won’t.”

That could mean free travel to Australia and some parts of the Pacific, but don’t expect a grand reopening any time soon, especially to the US and UK. “We’re going to be dealing with Covid-19 for some time yet,” he said.

The time will come to open Aotearoa’s door

It’s easy to imagine a world in 2022 of green zones without Covid, red zones with spread, and vaccine certificates allowing the vaccinated to travel and enter higher-risk areas like gyms, even in populations where the virus is still present.

Following a travel slump from Covid-19, some countries might then set high immigration targets to make up for border closures. Students could start travelling overseas to universities and business leaders could be jumping on jets to sign deals again.

It’s easy to imagine that world of 2022, because it’s all happening right now. Israel has rolled out a vaccine certificate system, Canada has set aggressive new immigration targets for this year while Europeans and Americans are travelling for work and study.

Looking ahead, economist Rodney Jones is worried that New Zealand could get caught flatfooted as the world moves on from restrictions, despite some ongoing presence of Covid-19. It’s a challenge other countries that have adopted the elimination model will also face. Because after a year of sparing their populations the worst of a terrible virus, they’ll now have to face the difficult question of when to risk opening their borders and potentially infecting some of that 20% of people who likely won’t be vaccinated.

“I’m pretty optimistic. Pandemics end and I think we’re on a better path than seemed possible not so long ago, and that’s to do with the number and effectiveness of the vaccines,” said Jones. “The elephant in the room is the path to reengaging with the world.”

Jones, who has also done some Covid-19 modelling, wants to be clear he isn’t advocating ditching the elimination strategy just yet. It was the right move by the government, but at some point in the fast-approaching future, the strategy might become counterproductive as most New Zealanders become vaccinated.

“We need to change gears here. What worked in 2020 won’t work in 2021,” he said. At a certain point, it will no longer be realistic to want zero Covid in the country, he says. If we continue to accept zero risk, New Zealand will be back on its way “to the 1970s” – an isolated south Pacific economy that keeps to itself and doesn’t trade much.

“I’m actually fearful of a return to a 1970s New Zealand. That would mean we’d be slow on the vaccines and even once we’re vaccinated, we’re fearful of new cases, we keep our borders closed, we keep MIQ open, and we’re slow to open with Australia. We’d just be slow on all fronts,” he said. “The public would remain fearful, and that anxiety and fear that was a strength in 2020 becomes our weakness.”

The alternative is to start opening up once most people have the jab, said Jones. That means allowing tourists and foreign students back into the country, both of which constitute some of the largest parts of our economy.

“New Zealand businesses need to travel and re-engage with the world or they will stagnate. There’s too much economic confidence right now. What’s thriving in our economy are the closed parts; what will start to struggle are the open parts. We need to dial back the optimism a bit and start grappling with these issues,” he said.

The government’s defence of its successful Covid strategy is that a strong health response has meant a strong economic response. That could be turned upside down in a world where other economies are back to acting more normally, despite a slow trickle of new cases and deaths.

“I think we’re underestimating how fast things are moving offshore,” Jones said.

A quarantine-free flight from LA to Auckland?

Nick Wilson, a public health professor at the University of Otago, has been one of the most public and vocal critics of the government’s border management. Wilson has warned that systems need to be strengthened after failures at border facilities resulted in community cases. We’re up to 11 failures now, he said, even though the government might call them “events or incursions”.

Looking forward a year, Wilson charts a more conservative path than Jones. He expects that with 70% to 80% of the population taking up the vaccine we should have something like herd immunity protecting most New Zealanders from Covid-19.

“That will give the government confidence to open up with similar countries, including Australia if they keep up with elimination, and Pacific and Asian countries where elimination has been successful,” he said. That group of Asian countries could include Vietnam, China, Taiwan and possibly South Korea and Japan.

It would also provide a large enough stream for the tourism industry to start up again, although without the massive crowds it’s relied on in the past. That would align with a recent report from the environment commissioner, Simon Upton, who said the industry needs to move beyond mass tourism.

“It would mean you could travel with your vaccine certificate and on arrival, there might be a safety test but no quarantine. But for the other countries that are grappling with outbreaks, I expect we’ll keep a cautious approach and there will need to be some measure of quarantine for some time,” Wilson added.

Wilson’s lofty aspiration for 2022 is that the world adopts the goal of global eradication. It would mean the end of the Covid-19 virus and the surest way to a return to pre-Covid living. But he admits that’s unlikely to happen.

His biggest concern over the next year would be reopening the border to current hotspots, particularly the US. It’s likely the virus will keep circulating in North America for years to come. Americans have shown incredibly high levels of vaccine hesitancy so far, with half the country telling pollsters they aren’t interested in getting a jab, one-third of the US military declining one outright, and 60% of nursing-home workers in Ohio – who serve the highest risk group out there – just saying no.

“It would be silly to open up without quarantine to a place like the US. If we have 80% vaccine coverage, they’ll bring in disease and we’ll continue to have outbreaks in the unvaccinated population, it’ll be chaotic. It’ll be like the situation we had in the last few years with measles, but the death rate will be greater,” said Wilson.

That could mean the need for quarantine from the Americas and possibly Europe for years to come.

Border facilities in 2022 should look completely different, according to Wilson. While Hipkins wants some tweaks, Wilson says it should be moved to prefabricated homes built on farmland around military bases like Ohakea. Start small, maybe 500 homes, expanding the number as time goes on. State governments in Victoria and Queensland, for example, are already looking at purpose-built MIQ.

“Knocking down Melbourne three times from failures in hotel quarantine facilities has taught the Australians to look at this seriously. This is a very small investment that could be made to work, compared to the cost of a $100 million per week Auckland lockdown,” said Wilson.

Hipkins, however, says that isn’t going to happen. “On paper, it’s a nice idea, [but] the practical realities of it make it very challenging. First of all, if we were to create a 4,500-bed managed-isolation facility, that’s very expensive and it would take quite a lot of time. You’re talking about a couple of years for the building work,” he said. Then there’s the trouble of getting all the staff to move out of Auckland to isolated areas. Finally, all the risk would be focused on one facility – it’s better to spread it across a network, according to the minister.

Wilson responds by saying if the government wants to continue to keep returnees in hotels, it should keep them in facilities overseas in Singapore, Hawaii and Dubai and quarantine them there before they hop onto a plane to New Zealand. Because if managed isolation is going to last for several more years. it’s time for longer-term thinking.

How long term?

Public health expert Collin Tukuitonga gets the last word. He says that while he expects people in New Zealand will flock for jabs, especially Pasifika people, this isn’t going anywhere. A real risk is that reservoirs of Covid remain active in the world’s poorer regions.

“When Salk found the vaccine for polio in 1953, they predicted it would get rid of polio in the world. In 2021 we still have polio in India, in Nigeria and close to us, in Papua New Guinea. He gifted the world his vaccine and we still haven’t rid ourselves of polio. That’s my sense of Covid-19.”