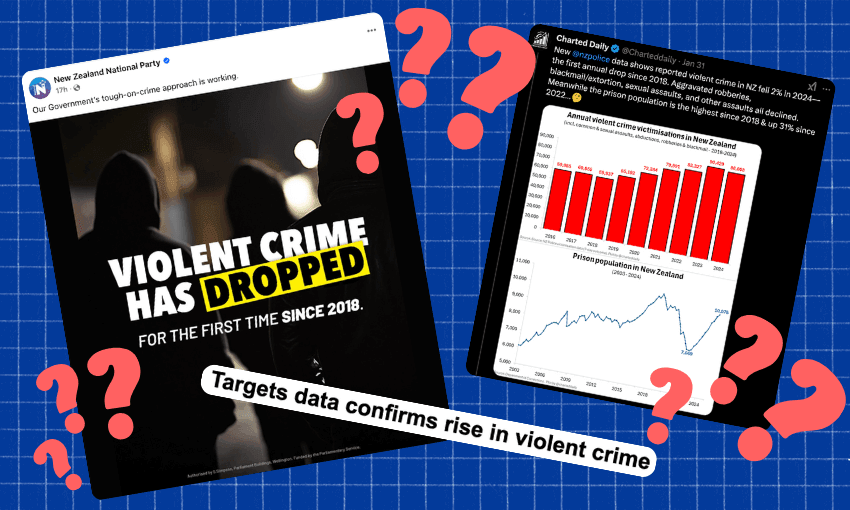

The government had some positive law and order news to share this week. The source for the claim? A tweet. But by the measure it’s using to track progress towards its own violent crime reduction target, it’s a different story.

On Tuesday afternoon, a shady-looking trio of hooded figures appeared in a post on the National Party’s social media accounts, the image overlaid with bold text proclaiming, “Violent crime has dropped for the first time since 2018.” There was no further context, but a press release from police minister Mark Mitchell and justice minister Paul Goldsmith had the details. “Police data shows that violent crime has fallen for the first time since 2018, indicating that the government’s tough-on-crime and victims-first approach is working,” it read.

“After year-on-year increases in violent crime since 2018, it is encouraging to see a reversal of this rise with a 2% drop in the numbers for 2024,” said Mitchell in the release. “It is especially encouraging when you consider that violent crime increased by 51% between 2018 and 2023.”

A 51% increase in violent crime in five years is an alarming stat, but as The Spinoff has detailed in the past, the NZ Police “victimisations” data the coalition government regularly uses to illustrate the previous government’s alleged “soft-on-crime” failures – and, now, its own “tough-on-crime” successes – comes with some caveats. It records all instances of reported crime for which there is a direct victim, even if no charges are laid – and an increase or decrease in potential crime being reported to police doesn’t necessarily mean an increase or decrease in actual crime. A Herald analysis from 2023 noted factors that may have contributed to a rise in police crime data, including better reporting mechanisms, such as the introduction of the 105 non-emergency phone line in 2019, and legislative changes, such as new offences added to the Family Violence Act in 2018.

The ministers’ press release is based on a January 31 tweet by X user @charteddaily, a fact that is mentioned at the very bottom of the press release:

It’s a curious footnote, given NZ Police has a data team who can crunch any numbers the minister wants at any time, and @charteddaily has used the same categories of publicly available police data that both Mitchell and Goldsmith have repeatedly used to reference an increase in violent crime in the past. The tweet compares a decline in these stats with Corrections data showing a rise in the prison population, a point also highlighted in the press release (and a comparison a team of professional data analysts may be reluctant to make). “This drop coincides with New Zealand’s prison population hitting its highest level since 2018, and a raft of other police statistics showing crime overall reducing, with total victimisations down 2%, and assaults and serious assaults both down 1%,” said Mitchell in the release.

The metric considered to paint a more accurate picture of crime rates is the Ministry of Justice’s annual New Zealand Crime and Victims Survey. This is what the government uses to set its reduced violent crime target (20,000 fewer victims of assault, sexual assault and burglary by 2029) and measure progress towards it. An annual, nationally representative survey of around 8,000 people that has been running since 2018, the NZCVS has a major advantage over police data in that it “captures crimes that are often unreported, such as sexual assaults and family violence”, as the violent crime target fact sheet itself noted when the target was set in April 2024. NZCVS results have suggested that only around a quarter of instances of crime are actually reported to police. It has also indicated that there has been no significant change in the annual number of victims of assault, sexual assault and burglary – violent crime as per the government’s official target to measure it – since the survey began.

That is, however, until the NZCVS began releasing quarterly data in order to fit in with the government’s quarterly target progress reports. It’s less reliable than the annual data due to complex reasons involving weighting and other survey minutiae, but the first such release, in September last year, dropped a bombshell: for the first time in the survey’s history, violent crime had increased significantly, rising from 185,000 victims for the year to October 2023 to 215,000 victims for the year to June 2024 (there is overlap in the time periods due to the way the survey is conducted and the new quarterly reporting requirement).

The NZCVS does get a mention in the ministers’ press release, towards the end. “The latest New Zealand Crime and Victims Survey also shows how effective our work to restore law and order has been,” Goldsmith said. “There were 24,000 fewer victims over the year ending October 2024, compared to June 2024.” The October 2024 data – which is the gold-standard annual data rather than the quarterly simulacrum – is set to be officially released next month, but Goldsmith has evidently had a sneak preview, and the number must be down (or up, depending on where you’re starting from) to 191,000.

“These results are extremely promising,” said Goldsmith, “but we expect the data to remain volatile before a longer-term trend emerges. There’s still more work to do.”

What the justice minister doesn’t mention is that while “24,000 fewer victims” may sound great, it’s still 26,000 above the government’s target of 165,000 – and still 6,000 higher than their starting point from less than a year ago. By that measure – which, remember, the government is using to track its own progress – violent crime has risen, not dropped.