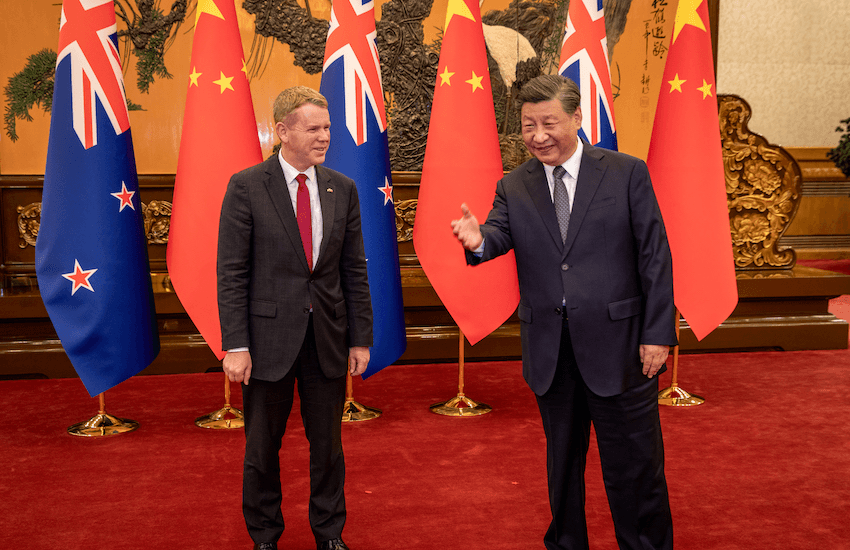

The prime minister met Xi Jinping for the first time in Beijing on Tuesday. Madeleine Chapman was in the room.

Before the meeting can begin, Barbados must be cleared from the room. The blue and yellow flags, at least five of them and each four metres tall, are carried out of the east hall meeting room in the Great Hall of the People by suited men and women, minutes before Chris Hipkins is scheduled to arrive. The New Zealand flags have either already been taken in or have been brought in through one of the other four entrances. Hipkins is at the grand state building to meet with Chinese president Xi Jinping, but he’s evidently not the only prime minister on Xi’s schedule. The prime ministers of Barbados, Vietnam and Mongolia are all in town, meaning there’s a room somewhere filled with the giant flags of four nations, ready to be deployed.

A man wearing a bowtie and white gloves exits the east hall with a tray of dishes from Xi’s meeting with Barbados prime minister Mia Amor Mottley. The tea cups are empty but the dessert, which looks like a crumbly nightmare to eat in front of one of the world’s most powerful people, is untouched. Dozens of Chinese officials mill about wearing near-identical dark suits and ties, all wearing masks despite there being no Covid restrictions in China since February. Everything is quiet and feels like being in church.

Like everything in Beijing, the Great Hall of the People is, well, great. Built in 1959 as one of 10 “great constructions”, the hall is 356 metres long and 206 metres wide, with marble floors throughout. Situated on the western end of Tiananmen Square, it’s hard not to think about the 1989 massacre and how much (or how little) has changed since then.

Hipkins, who arrives about 20 seconds after the last Barbados flag has been safely placed behind a giant velvet curtain, is unlikely to discuss Tiananmen. Nor, as we would later learn, is he likely to discuss, at any length, the current human rights issues concerning China – the persecution of the Uyghur people in Xianjing, the ongoing support of Russia in the war in Ukraine, the increasing militarisation of the Pacific.

It’s all a strange affair, really. The slogan being muttered by media throughout the week is “hurry up to wait”. After weeks of harried speculating about the crucial meeting between Hipkins and Xi, it all culminates in… a six-second handshake with oddly splayed hands from both parties, four minutes of polite introductory remarks, then 36 minutes of talks that no one will ever really know the contents of.

Even without knowing the full remarks, every little detail means something. Hipkins’ meeting was confirmed weeks in advance, which is a positive. Anthony Blinken, the US secretary of state, had his meeting with Xi this month confirmed mere hours before it happened. And the seating matters. To meet Blinken, Xi adopted an unusual U-shaped seating arrangement, with Xi at the top, and US and Chinese officials down each side. Besides being quite funny, the seating was successful in showing who Xi believed to be in control. For someone who possesses such extraordinary and singular control, he rarely feels the need to make it so obvious. It’s more subtle, like his refusal to lean forward (a fairly natural bodily response) when shaking hands.

Before Hipkins enters the room, Xi is told exactly when to position himself in front of the Chinese and New Zealand flags so as not to be waiting more than a few seconds. Hipkins rounds the corner, positively grinning, and extends his hand. Xi takes it, smiles and lets Hipkins lean in to close the distance without standing uncomfortably close. Both leaders’ hands are splayed in a way that doesn’t look natural for a handshake (Hipkins later insists this is just how he shakes hands). It lasts six seconds and a few pleasantries are exchanged through a translator before the two part ways.

The Sino-NZ relationship reaches back further than the 50 years since formal diplomatic links were established, and New Zealand is looked on fondly as an early adopter of Chinese connections. To go way back, there have been Chinese New Zealanders for nearly as long as there have been Pākehā New Zealanders. Chinese have migrated since the 1860s, looking originally for gold and eventually a home.

Xi nods to the history of the relationship, and its position in a global diplomatic context, in his opening remarks while flanked by seven senior officials (all men). “I am aware that the international community, especially countries in our region have been following your visit very closely,” he says. “We should work together to kickstart a new 50 years of our bilateral relations and promote steady and sustained progress in our comprehensive strategic partnership.”

That’s what he’s saying but it sounds a lot like don’t listen to those guys, you’re my friend and that’s what matters. He’s speaking from a gigantic table, almost 10 metres away from Hipkins’ gigantic table, in a room the size of a hockey field, but it sounds friendly.

He actually says as much explicitly: “China always views New Zealand as a friend and a partner.” It’s a recycling of his remarks to Jacinda Ardern in 2022 but who’s counting. Hipkins smiles, though after the meeting he’ll hesitate to call China “a friend and a partner”, obfuscating and avoiding questions from media until eventually reciprocating what is clearly a mere pleasantry.

To many commentators, Ardern oversaw the cooling of the Sino-New Zealand relationship. That included the blocking of Chinese telecommunications company Huawei’s involvement in the introduction of 5G to Aotearoa, citing “national security risks”. Not a small call to make given Huawei’s ubiquity in New Zealand for the years preceding the decision. But Ardern was also seen as less effusive in courting our largest trading partner. Admittedly, there were other, more pressing events happening for most of her two terms. In 2019, a scheduled week-long visit was reduced to one day in the aftermath of the Christchurch terror attacks. The following year, both countries shut down and China wouldn’t reopen until February this year, mere days after Ardern announced her resignation as prime minister.

In 2022, the pair had a brief (though longer than expected) talk at the Apec summit in Bangkok, which Ardern said was “constructive” and included her directly speaking to their “differences”. Hipkins’ go-to descriptor for his own meeting with Xi is “warm and constructive”, and Xi does genuinely look warmer when speaking with Hipkins than he did with Ardern. Perhaps because Hipkins has no intention of getting into any tough conversations about human rights issues.

This week, Hipkins has tried wherever possible to stick to an emphasis on trade. His core message: New Zealand is (still) open for business. “There’s not much more bread and butter than trade for a country like New Zealand,” he said in preparation for the trip. That mantra is present in the meeting with his Chinese counterpart. Warm bread and constructive butter.

In an election year during which Hipkins is fixed upon avoiding distractions, and following an Australian media report this week that suggested foreign minister Nanaia Mahuta was subject to an “epic haranguing” across the course of an hour by her Chinese counterpart when visiting Beijing in March – reports which both Hipkins and Mahuta have stopped short of denying – Hipkins will be even more determined to stick to his bread and butter script. And one way to keep the bread and butter flowing is to not talk about things your largest trading partner doesn’t want to talk about.

While few would genuinely believe Hipkins could sway Xi on geopolitical matters, there’s an expectation – or at least a desire – among New Zealanders for leaders to be staunch on moral matters. For Hipkins to voice concerns around issues such as the contest for influence in the Pacific, or the atrocities in Xinjiang or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. To be a loud voice in a room few are allowed access to. Like signing a petition with the world’s largest pen.

But Hipkins focuses on the matter of trade and business, though not the trading of culture, as “in terms of the Māori to China relationship, that’s not something we spoke about particularly”. He sits in front of his tea and dessert, presented to only he and Xi, with their respective officials receiving only water, smiling and nodding. And behind closed doors, he only “references” the human rights matters, rather than discusses them. Xi’s reception? “All of the messages that I was conveying were well-received – or received.”

That’s typically all that can be expected of a meeting with a global superpower. Forty minutes later (the meeting runs over by 10 minutes), Hipkins leaves, taking the long walk out of the Great Hall and into the sweltering heat having not turned a friend into a foe. In fact, he even got what appeared to be a genuine smile from Xi. As he exits, the “formidable building” that is the Great Hall of the People towers over him, an unsubtle reminder of the size and power difference between the two nations.

Inside the marble walls, the five giant New Zealand flags will be quietly removed from the east hall, making way for the next friend and partner.