For our new deputy leader, the name Waka Kotahi is the ultimate example of the woke silliness he’s rallying against. But words having multiple meanings is not some modern perversion, and waka is no exception.

As part of his ongoing crusade to rid New Zealand of wokery, conniving cultural cabals, elite virtue-signalling and bulldust of all kinds, our new deputy prime minister is planning to make public service departments use their English names instead of their te reo ones.

Winston Peters has been flogging this particular policy pony since at least March, and it was one of NZ First’s big wins in its coalition deal with National, which was finally signed on Friday. When he’s spoken about the policy, Peters cites the potential for confusion: people might not know what a government agency does if they don’t understand its name, he reckons.

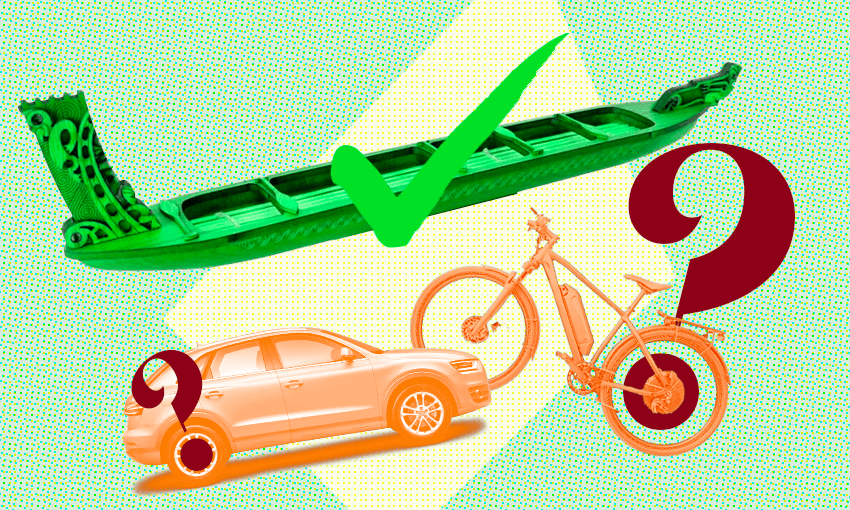

From the get go, there has been one agency name that particularly pisses off the NZ First leader. It’s not Te Whatu Ora, Oranga Tamariki, Ara Poutama or Whaikaha, though those no doubt irk him too. He’s reserved the bulk of his disdain for Waka Kotahi, AKA the NZ Transport Agency. Why? Because this organisation is focused on land transport, and you know what doesn’t travel on the land? A waka. A waka, as everybody knows, is a canoe. And a canoe, as everybody knows, is “a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using paddles”.

“How can you have a waka on the road?” Peters asked Heather Du Plessis-Allan incredulously on Newstalk ZB after the coalition deal was signed on Friday. Clearly not satisfied with her failure to answer this simple question, he tried a variation on reporters following the swearing-in ceremony on Monday. “Tell me this, how many boats have you ever seen going down a road?” he spluttered in what, ironically, was probably the least problematic comment of that particular stand-up. He then repeated, with extra exasperation: “How many boats have you seen going on a road anywhere in the world?”

In terms of getting an answer, Peters had more luck with his quest for knowledge back in March during an interview with Māni Dunlop on RNZ. “Why would you have a waka on the road?” he asked. “They belong to the sea.” Dunlop responded that waka was “an interpretation of a moving vehicle”. Peters pointed out that “the only vehicle they had at the time”, presumably meaning when te reo Māori came into being, “was on the water”. Dunlop said, with a sigh, “language adapts”.

But Peters – not unlike Invercargill mayor Nobby Clarke, who is out to rid the world of metaphors – is clearly a literal fellow, and he didn’t buy this woke virtue-signalling “language adapts” business.

Fair enough. Change is scary. And, while I acknowledge the problematic nature of a Pākehā upstart with a few night classes under her belt and a passion for online research explaining a Māori term to a Māori man, I thought I’d lay out a few things in case anyone else is as confused about it all as Peters. (After all, my Māori peers in the media might already have their hands full with this government’s many problematic policies pertaining to tangata whenua, so I figured I could take this one.) So here are all the reasons why having “waka” in the name of a transport agency actually makes a whole lot of sense.

Firstly, and most obviously, words can have more than one meaning. In addition to being a canoe, a waka can be a vessel or receptacle of some sort, for example a waka huia (a treasure box), or a waka atua (a person through whom a god is being channelled). It also means a vehicle of any kind. While the official word is motokā (from motorcar), it’s very common for people who speak te reo to refer to their cars as waka. I struggle to believe Peters doesn’t know this – surely if his mate Shane Jones, a fluent te reo speaker, said to him after a session at the Duke: “Winnie, hop in my waka, you’ve had one too many whiskies to drive yourself,” Peters would head to the carpark, not the shore?

It’s not just cars: anything that moves will likely be called a waka. Waka rererangi: plane. Waka pēpi: pram. Waka rōnaki: roller coaster. This, perhaps, would be cold comfort to Peters, who has already taken issue with the concept of a waka in the sky and would no doubt think the fact rollercoaster had been given a Māori word at all was woke bulldust of the highest order. (It’s worth noting that this is a convention used in many Pacific languages: in Niuean, a plane is vakalele and in Sāmoan, va’alele. Both translate literally to flying canoe.)

But as much as Peters would like to believe this language quirk is a modern perversion, I’d wager that Māori have been calling cars waka since the first vroom vrooms arrived on these shores. Hell, even Apiranga Ngata, Peter Buck, Māui Pomare and James Carroll – to whom Peters refers on a weirdly frequent basis in an attempt to explain why things in the past were better – probably called them that.

You want proof, Winston? Take the example listed right underneath the word “waka” in Te Aka, the Māori dictionary (italics added by me): “Ko ngā tiriti o tērā tāone kapi tonu i ngā tū āhua waka o te Pākehā, mai i te hōiho kawekawe mīti a te pūtia tae noa ki ngā tū āhua katoa o te taramukā”. The translation given, with italics again added by me, is, “The streets of that town are full of all sorts of vehicles of the Pākehā, from the horse carrying the butcher’s meat to all sorts of tramcars.” The source? Not some woke government document from the 21st century, but a 1909 edition of Māori language newspaper Te Pipiwharauroa.

To bring in another of Peters’ interests, vaccine mandates, let us turn to an example from the 1913 smallpox epidemic, when all sorts of restrictions were placed on Māori and Māori only. This notice in te reo, printed in multiple newspapers at the time, said Māori could only travel on a “public conveyance” if they’d been vaccinated. Various forms of public transport are listed, such as railway, steamer and tramcar, with the addition “era atu tu waka ranei e tuwhera ana ki te katoa” – or any other “waka” that’s open to everyone.

I can go earlier and weirder to prove that “waka” has been more than a canoe for a hell of a long time. How’s an 1883 reference to a hot air balloon, or waka i te puruna, from Māori language newspaper Korimako, for you?

Turns out words can have many meanings, or even just one meaning with many applications. Hopefully this little guide has demystified one of those words for you, dear reader, and for our deputy prime minister (for the next 1.5 years).