A new Auckland Museum exhibition promoting some of Robin Morrison’s photographic mahi coincides with a renaissance of analogue photography among rangatahi.

The clothing when Jake Morrison was a teenager and young man in the 80s and 90s is fashionable with rangatahi again. Not only is “vintage” 80s and 90s clothing popular once more, so is film photography. Although most people nowadays have a high-quality digital camera in their phone, single-purpose disposable cameras, film point-and-shoots and DSLRs are roaring back to relevancy. Film itself has been in hot demand. New Zealand has experienced film shortages over the last couple of years brought about by Covid-era supply chain issues.

While some young people still take dozens of selfies and make use of ring lights and photo apps, others are embracing the beautiful imperfections of traditional photography. Experimenting with different films, unique lighting and new subject matter makes manual photography an exciting – albeit expensive – endeavour. You never quite know what the result will be, and waiting for a roll to get developed feels a bit like the lead-up to your birthday or Christmas as a kid.

However, for those rangatahi who have championed the rebirth of film photography, finding sources of local inspiration can be challenging. After all, digital photography is the dominant medium used to document life now. Many young people would have only seen the film photography of Ans Westra, for example, until the tributes after her passing. However, for those seeking guidance in the bygone ways, the Auckland Museum is showcasing another potential source of inspiration.

Selected works of Robin Morrison – Jake’s dad – are currently being exhibited at the museum. Morrison senior is one of New Zealand’s most acclaimed and beloved photojournalists and documentary photographers. But he remains largely unknown to rangatahi, even though many have seen his mahi already. Of particular note are Morrison’s photographs of the historic protests at Takaparawhau (Bastion Point) and the Springbok Tour. The images he took at both are immortalised in the minds of New Zealanders of all ages.

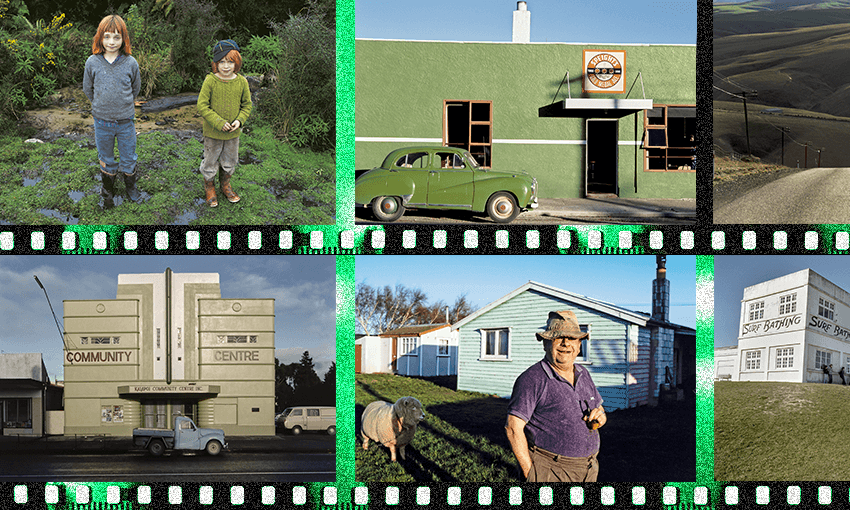

The exhibition, Robin Morrison: Road Trip, is now free to view for locals at Auckland Museum. Coinciding with the show is a reprint of the book The South Island of New Zealand From the Road, with an updated introduction and new photographs. The show itself features almost 50 of Morrison’s most “striking, unpretentious images” from a 1979 family holiday around Te Waipounamu blown up to the size of one metre on light-boxes. Seeing Morrison’s work presented in this manner is a very confronting way to see just how much New Zealand has changed since 1979, but it inspired me to pick up my dusty but trusty film DSLR, which is older than my mum, for the first time in a while.

Auckland Museum’s Samantha McKegg describes Morrison’s work as “humorous, humble yet super revealing photos of New Zealanders and the space we live in.” Jake Morrison thinks the exhibition is “an opportunity to re-appreciate dad’s work,” particularly for the younger generation of New Zealanders to whom his dad isn’t a household name. Jake was eight years old when his dad took these photos on their family road trip. “I hope that seeing what New Zealand used to be like is something young people get value out of.”

Morrison was known for photographing forgotten New Zealanders who he saw as being on the “fringe”, according to the museum’s pictorial curator Shaun Higgins. Those on the fringe included rural people, who are a big focus of this show. Blowing up Morrison’s work onto the huge lightboxes helps his beautiful compositions to really pop and enables the striking colours of the kodachrome film to glow radiantly.

Robin Morrison was a master of his craft, whose life ended far too early – a few months before his 49th birthday. But with a new generation falling in love with film photography, hopefully the Robin Morrison: Road Trip exhibition will inspire a newfound appreciation for his work. No doubt that after seeing the exhibition, film fanatics will be motivated to go capture life in New Zealand just like Morrison did. His son Jake is “stoked”, and “delighted that a new generation will be able to see dad’s work.”