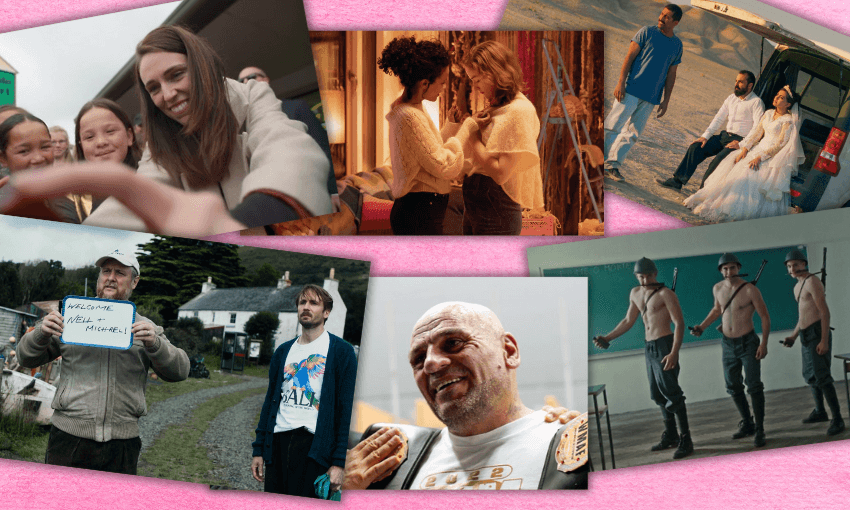

A Palme d’Or winner, the Jacinda Ardern documentary, cage fighting in Kaikohe and more – reviewed.

It Was Just an Accident

The Civic was buzzing on opening night of the New Zealand International Film Festival and few films could’ve justified the packed house like It Was Just an Accident. Hailed by festival director Paolo Bertolin as the first truly deserving Palme d’Or winner in years, the Iranian drama delivers a taut and affecting meditation on justice, memory, and the price of survival. When a group of former political prisoners encounter the man who once tortured them, the film becomes a quiet reckoning – not just with the past, but with the uncertain line between forgiveness and vengeance.

Director Jafar Panahi, long a master of subversive Iranian cinema, handles the material with precision and grace. The cinematography is luminous, but never distracts from the film’s emotional core, which is often laced with unexpected moments of humour – the kind that briefly disarms before plunging deeper. Though rooted in Iran’s political landscape, It Was Just an Accident speaks to universal dilemmas of power and reconciliation. It’s a film of rare weight and restraint – one that lingers long after the credits roll. / Liam Rātana

Prime Minister

I assume no other film festival film has started 30 minutes late because a protest outside and beefed up security meant a very slow entry into the Civic for 2,400 viewers. A documentary about Jacinda Ardern, even two years after she’s resigned as prime minister and left the country, will do that. Once it got started, my heart sank – an opening shot both “observational” but clearly orchestrated of Ardern dropping Neve to the school bus in Boston before strolling peacefully to Harvard. Would this be a long wellness ad for working at Harvard?

Thankfully, it quickly jumped back to 2017, with Ardern about to become Labour leader. There’s familiar footage of press conferences and newslines intersected with genuinely enthralling snippets of Ardern’s phone calls at the time with the Alexander Turnbull Oral History Project, which are not supposed to be released until after Ardern’s death. They’re incredibly candid – more candid even than Ardern was in her own book – and give the film that extra emotional weight.

It’s very hard to properly review a film that covers events most New Zealanders experienced, through one very powerful person’s perspective. But if I watched something like this about any other world leader, that had this much access and candour, I would love it. Clarke Gayford has a cinematography credit as the person who filmed a lot of the more intimate moments (Ardern drafting her resignation press release in bed; stressfully reading updates on the mosque shootings). If I left with one impression it’s that I can’t believe she didn’t break up with him through all of that. / Madeleine Chapman

Fiume o Morte!

The footnotes of history often make the best documentary subjects, and this is very much the case for this documentary by Igor Bezinović, who trains a lens on his hometown, Rijeka in Croatia, and the 18-month period when it was ruled by a proto-fascist Italian aristocrat, army general (and poet!) Gabriele D’Annunzio, and called Fiume.

Bezinović’s enlisting of the citizens to reenact historical events is a genius format; doing more than just humanising and placing the history in a present context, each brings their own memories, cultural identity and role in the community to the character. D’Annunzio, fuelled by hubris and cocaine, is played by numerous bald men, including a dustman and someone in a punk band.

Taking over the city was farcical (though not without very real pain and loss of life) and there’s a level of absurdism to the retelling – his loyal, strapping foot soldiers must know how to fight and jump over things but also dance and sing – and it all happens as modern life goes on around it.

It’s a darkly funny film – there were lots of laughs to be heard at The Academy – and though hyper specific to a region of complex cultures and identities, the broader story is one of the shifting identities of a city, how pasts and presents that often coexist in one place, what we decide to forget and how we chose to remember. See it if you can. / Emma Gleason

Kaikohe Blood and Fire

Yes this is about an MMA club in a small Far North town — a simple premise on paper — but what Simon Ogsten’s documentary really delivers is a gut-punch about the community men crave and where they go to find it. We see the members of Team Alpha find a sense of brotherhood and support alongside the physical rewards (and risks) of the sport, the outsized role the club plays in Kaikohe, we get a sense of where they came from and what hole this fills for them.

Ogsten captures the violence, of course, but also the desire for it. At the start of the film, one subject explains how he loves a war and wants a “wild, mongrel fight”, a shocking declaration for some viewers, but one that comes from a deep place and a long, expansive history of martial culture. What that looks like now, how we satisfy such desires and the place they’re given in society, puts the sport in context.

Contemporarily, violence is both frowned upon and rewarded, depending on where and who’s doing it. MMA is booming, in the big leagues and small towns like Kaikohe. After watching this I “got it”, that primal why and modern need, and it makes you think. / Emma Gleason

Dreams (Sex Love)

A bit of a risky choice from me, knowing nothing about the trilogy(!) of films from Norwegian director Dag Johan Haugerud. Dreams is the final release (after Sex and Love, also showing at the festival) and follows 17-year-old Johanne as she falls head over heels in love with one of her teachers. She writes evocatively of her feelings and interactions with the teacher and eventually shows her writing to her mother and poet grandmother, who debate the ethics of the situation as well as the quality of her writing.

Haugerud’s greatest achievement in Dreams is accurately, and without condescension, conveying the brutality of a first love and the sense that nothing else in the world is more important or more painful. We view Johanne’s relationship with her teacher first through her infatuated lens, then through her guardians’ protective lens, then through a subjective, analytical lens as her teacher responds.

As is often the case in life, there are no clear villains or heroes, just women of different generations trying to navigate a teenager’s powerful crush. Despite a heavy use of voiceover (which is not my preferred narrative technique) I found myself engrossed in Johanne’s emotional processing and maturation.

Near the start of the film, Johanne describes wanting to tell her teacher how she feels. She’s terrified that her teacher will either get mad or, even worse, “laugh condescendingly, like when a child says something adorable”. It’s a relatable and brutal feeling, made all the more ironic throughout the rest of the film as viewers around us laughed at her romantic despair over and over. May we all never forget the agony of a first love. / Madeleine Chapman

The Ballad of Wallis Island

I turned up to The Ballad of Wallis Island 15 minutes late and stressed to high heaven, scurrying into a seat in the back row as Tim Key was giving a sopping wet Tom Basden a tour of his big old house on what I knew from reading the blurb to be a remote Welsh island. Within literal seconds a smile had involuntarily spread across my face and not a minute had passed before I was full-on chuckling along with the rest of the Civic crowd, which I think tells you everything you really need to know about this film.

Story wise, Key plays Charles, a lonely widower and 2x Lotto winner who basically Parent Traps his favourite folk duo, McGwyer Mortimer (Basden and Carey Mulligan), into reuniting to play a one-off gig for him on the island, unwittingly forcing them to confront the pasts they’ve been simultaneously stuck in and running from. A huge part of this movie’s appeal lies in the chemistry: Key and Basden have been friends and comedic collaborators for years (Wallis Island started life as a short film they made together in 2007), and Mulligan slots into the dynamic seamlessly.

This is a warm, gently quirky comedy with a strong undercurrent of melancholy, in other words ideal film fest fodder – worth seeing with an audience you can laugh along with. / Calum Henderson