It’s hard to make good art about the formless catastrophe that is climate change. Scenes from the Climate Era hits all the right notes.

Darkness, then a flash. The play Scenes from the Climate Era begins with a couple arguing about the ethics of having a baby when you know a more unstable world is coming. It’s the first of about 50 scenes – some taking the form of postcards or TikTok feeds – depicting dozens of different reactions to climate change. The script requires actors to shift emotional registers in a split second, from a series of people briefly describing the last flight they took and how they felt about it, to a therapist cheerfully pointing out that their client’s fear is completely reasonable.

Initially performed in 2023 in Sydney, this play by Australian writer David Finnigan eschews a standard narrative form for succinct, punchy scenes, sketching 500 different faces of climate change. Most scenes open with a brief description: the 1980s in a television studio, the 2030s in Antarctica, the 2050s in Sydney, 2021 in Glasgow. The script has been adapted for New Zealand by director Jason Te Kare and Tom Doig with input from Finnigan, and features lots of Aotearoa place names among international locations.

The show culminates in four scenes of unfolding crisis: Dawn Cheong as a prepper realising only community could have saved her from a fire; Arlo Green (Miles from Nowhere) as a climate activist demented by the hopelessness of UN climate talks; Sean Dioneda Rivera as a helpless son whose mother couldn’t be evacuated from an oncoming storm in Tairāwhiti because the buses weren’t wheelchair accessible; Amanda Tito as a parent in 2050s Sydney, after 10 days of 55-degree temperatures, whose baby is dying as they try to reach a place with air conditioning.

As the scenes flickered together, I allowed myself to feel some of the grief and urgency about the climate which I all too often joke about in lieu of truly dwelling in the emotion. My face was slippery with tears, my breaths uneven behind my mask.

In format and content, it resembles The Ministry for The Future, Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2020 climate novel portraying different ways the world takes action on climate change. Both feature dramatic scenes of deaths in heatwaves, portray geoengineering in Antarctica and the stratosphere, and partying among it all.

However, unlike Robinson’s climate tome, Scenes from the Climate Era bears no resemblance to a policy brief: instead, it’s more anthropological, or descriptive. If the question is “what does climate change look like?”, Climate Era’s answer is: it looks like this. The audience is automatically emotionally implicated – there’s a self-aware nudge early on, where a character apologises to their date for complaining “about that climate play”. (It turns out the date just wants to inform them that they’re a close contact for herpes).

Where does my superficial joking about climate despair come from? Maybe the sense that fear is a pretty boring emotion: it doesn’t go away. To adapt a refrain from Scenes from the Climate Era: I wake up every morning and check the news. There is always a headline that is touched by environmental devastation, even if it isn’t framed by it. News: multinational corporations asking for guarantees of ongoing climate subsidies from the government. Sports: athletes enduring an extreme “heat dome” at the Olympics. Business: a failed deal to convert trucks to being fueled by hydrogen. Or the obvious one: last week saw the hottest ever average global temperature recorded, followed promptly by the record being broken again. Despite this, we must remember that there is every reason to believe that this will be one of the coolest years of the rest of our lives.

As Amitav Ghosh has written about in his excellent short book The Great Derangement, standard narrative forms don’t work well when you’re writing about the climate crisis. We’re used to stories about individuals, with beginnings, middles and ends, and a measured amount of improbabilities. It doesn’t seem like a good story when several one-in-100 year floods happen all in a row. Instead, climate change takes many forms, implicates and affects so many people, and has no clear or resolved ending.

New kinds of storytelling might be necessary, and Scenes from the Climate Era responds to this challenge. It’s a climate era, not a “crisis”, for example, because we don’t know when it’s going to end; but it certainly won’t be in the short term, like “crisis” implies.

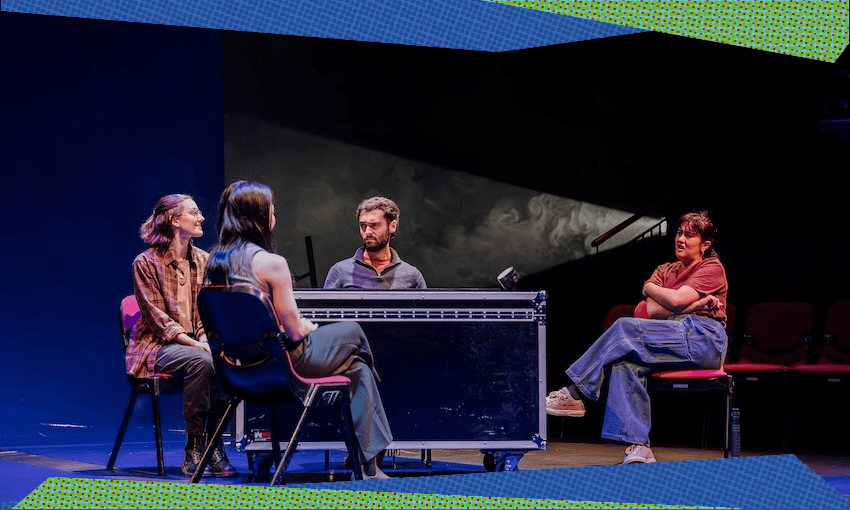

The scenes of this non-individual narrative unfold within a minimal set – there are a few chairs and blue shapes on the floor that look like a wave, or a rising bar chart of our emissions – which speaks volumes about the actors’ versatility. Accents shift in seconds, and suddenly, without even a costume change, a new character appears. The production also owes a lot to excellent lighting design, switching scenes quickly from a rave to a courtroom box to, most gorgeously, flowing pools of eels made of hands threading around upright torches.

Despite the despair, Scenes from the Climate Era is willing to be very fun, and very funny. At one point, a scientist ( Tito) performs a monologue about caring for an endling, the last individual of a species. It’s hard to stay too focused on the bleakness, though, because Sean Rivera is spotlit beside them, posed as a frog, occasionally croaking. Tito and Rivera were also the standouts of the other funniest scene in the performance, as focus group attendees discussing a new renewable energy development in Northland. Tito says nearly nothing, with their elongated body language on a stiff chair the picture of disaffection, while Rivera has the best “grandpa voice” I’ve ever heard, muttering about windmills slicing birds to ribbons.

There’s lots to worry about, but the whole theatre was laughing at Arlo Green playing a tech-bro type who inventing a new kind of ecosystem to replace coral reefs.

Where Scenes from the Climate Era succeeds most, it’s with this symphony of different emotional registers. Cheong, a scientist told to “be hopeful” about the devastating reality of increasing temperatures, brings bemused, frustrated fury to the stage as effectively as she did in The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom, also from Silo Theatre. Nī Dekkers-Reihana is exhilarated and nihilistic as a partying fighter pilot trying to cool the sun, then insouciant and cheerful as a young person off for a swim in a climate-changed future, where Piha’s Lion Rock has long been known as an island.

Often, my climate distress is a species that longs for plans and commitments. I eat less dairy and no meat, change to a more sustainable Kiwisaver (for what future?), keep fixing my bike. Scenes from the Climate Era is certainly interested in climate action, as the “my last flight” sequence shows. In the explosive second scene, Dekkers-Reihana describes to audience members how to use the small lentil we were given in an envelope upon entry to deflate an SUV’s tyres. A theorem: if climate change is everywhere, then take heart; wherever you go, there is work to do.

Can climate art mean something even if it doesn’t lead to direct action? The show must hope so: leaving the performance, having laughed and cried, the low-grade fear less abstract for the show’s articulation, I passed a theatre attendant with a basket, taking the lentils back.

Scenes from the Climate Era is playing at Q until 24 August. Buy tickets here.