Shanti Mathias attends a new play about the impossibility of authentically representing Aotearoa’s diverse Asian communities.

Watching a play as intelligent and meta as The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom is an invitation to show your hand before you play your cards. So let’s start there: when my editor asked me to review the show, I assumed it was because I am currently the only Asian staff writer employed by The Spinoff. The Spinoff is based in Tāmaki Makaurau, a city where, at the 2018 census, 28% of the population identified as Asian.

I didn’t really want to write that last sentence. I suppose it’s because, like the character of the Showrunner in the play, I like my job, my colleagues, and the institution I work for. I feel grateful for the opportunity I have to write here – and compelled to perform that gratitude, so the opportunity isn’t taken away. But when the performance you’re reviewing is so clear about the impossible contradictions of being asked to represent a group of people as diverse as the Asian diaspora, it feels only fair to be clear about the structures of representation you yourself exist within. So here I am, one small piece of the Asian diaspora, reviewing The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom.

The show, written by Nahyeon Lee and playing at Q Theatre until November 27, is in three parts. In the first, the audience watches the supposed pilot of New Zealand’s first primetime Asian sitcom, a Friends-like set up: messy young people in love with unattainable people, canned laugh tracks, exaggerated facial expressions. But this is an Asian sitcom, which the characters work hard to remind the audience of: an Indian character exaggerates his parents’ accents, a Filipina character gets offered good Catholic boys to date by her mum, a Korean character has, reluctantly, become a doctor.

In this part of the show, there were some genuinely funny lines, smothered by the canned laughter. The audience watches the characters directly, the hollowness of the set obvious, an uneasy voyeurism created by the screens at the front of the stage. These screens film the action for the Showrunner, whose voice projects over the stage, giving orders and encouragement.

As I biked to the show I tried to write pieces of this review in my head. I was going to lead in with a personal anecdote – perhaps the story of when, as a five-year-old, I asked my mother why I wasn’t allowed Barbie dolls. “Because they make people think that the only way to be beautiful is to have blonde hair and long legs,” she said. “But mum,” I apparently replied. “I do want to have blonde hair and long legs.” (White people love hearing anecdotes like this, incidentally; they laugh awkwardly, give you sympathetic wide-eyed looks and tell you they’re listening, and feel very self aware.)

Or perhaps, given that I knew the show involved writing, I’d write a few sentences about the novels I wrote as a teenager, promising myself that the protagonists would be confused brown girls like me. Hundreds of thousands of words about a grumpy and indecisive teenage lighting designer; an inquisitive but reluctant journalist discovering a government plot to use magic as a weapon; a lonely climate negotiator trying to win a deal to keep her country wealthy.

In that version of the review, I was going to then explain how my hunger for representation as a teenager had resolved into a scepticism of representation politics. How headlines about Simu Liu being the first Asian Marvel superhero or Rishi Sunak being Britain’s first brown prime minister didn’t seem to really mean anything material for the diverse needs of their diverse communities; non-white people operating in systems of power designed to enrich the global elite was a veneer over the transformative structural change needed to create justice for all. How it feels unfair to say this, when so many white and non-white people within those systems – perhaps including myself – do genuinely feel like they’re trying to change things for the better.

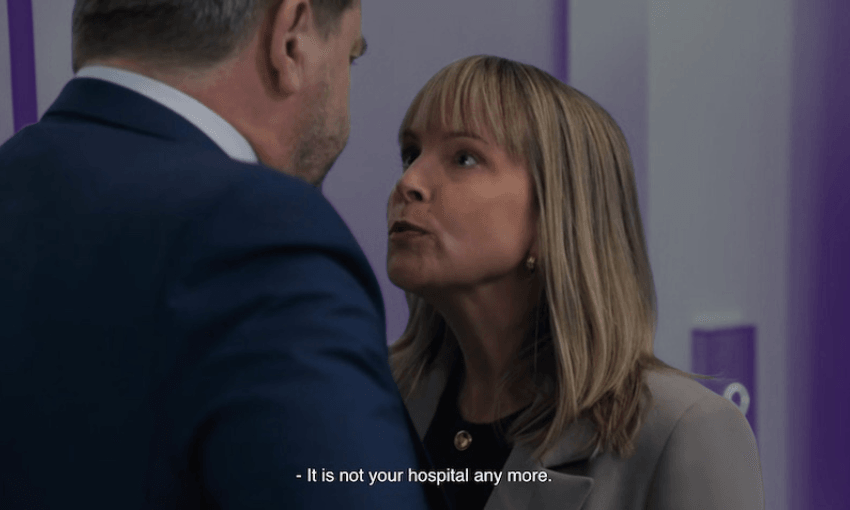

But I couldn’t write that review, because Lee has written a show that knows how preposterous it is for any show to represent everyone’s experiences. In the second act, a curtain is drawn over the stage, and the actors change costumes, all except The Showrunner (an incandescent Dawn Cheong) who is the point of consistency through the three parts of the play. Now the audience is watching a slightly awkward panel, the kind you might have seen at a writers festival. A social media influencer, an academic, a memoirist, and the Showrunner are invited by a moderator to “broadly” discuss their thoughts on representation. There’s a history here: the influencer has said on his Instagram stories that he didn’t like the first primetime Asian sitcom. The Showrunner is trying to justify the use of accents for humour and the attempt to broaden Asian experiences to be legible to a mainstream, implicitly white, audience. It devolves into a shouting match, the moderator compellingly stressed as she loses all control.

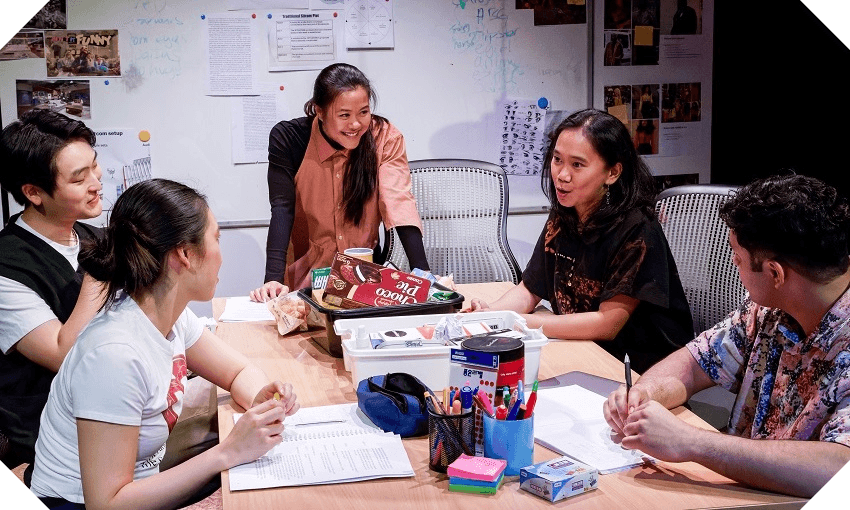

Then the action shifts to a writers room, the same actors now playing writers working on the script for another episode of the Asian sitcom. “I don’t want dour immigrant pain,” says one writer. “But these things do exist” rejoins another. The Showrunner is inviting them to bring their own experience to the writing process, but this reveals the tension in the “pan-Asian” writing room, who try to create a representation of a single immigrant experience that doesn’t exist. The questions all turn to centre on the Showrunner, trying to negotiate a path between authenticity and being palatable to white audiences. She’s very, very angry.

Despite the angst, the show is of course very funny. The titles of the Asian writer’s books on the panel (including “Banana: How I stopped loving to hate my identity”) were delightful, especially the note that they had “topped the Unity Books bestseller chart for five weeks running”. I particularly liked the writers listing Asian stereotypes to parody, from Dungeons and Dragons to kawaii girls to Asian goths, each suggestion scribbled furiously on a whiteboard by the Showrunner.

On a technical level, too, The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom works perfectly. The set is excellent – every part of the space used to its full effect. The sound and lighting design, from macabre green flashes of light to the tinny karaoke track of ‘I Want It That Way’ bracketing the final part of the initial sitcom, lends a sense of disquietude to the entire performance, pointing the audience to the explosive ending. Nothing seems quite right, because any authentic representation of an Asian experience will, and must, fall short.

If there’s any moment of hope in The First Prime-Time Asian sitcom, it’s certainly not at the end, where the Asianness of the set – anime titles on a shelf and Korean snacks on the writers table – is destroyed by the Showrunner’s Asian rage. Shifting coloured lights and an old-timey American song exhorts everyone to laugh while the Asian actors force themselves to dance through the futile task of authentically representing their communities.

Instead, it was a moment after the panel discussion that grabbed me, where the “enfant terrible” influencer is apprehended by Cheong’s Showrunner. She’s playing nice, she says, because she doesn’t want her first primetime Asian sitcom to also be the last one. She knows she can’t win, but she’s trying. He seems to listen. It’s the most human exchange in the show, perhaps because it takes place backstage of the panel. The characters aren’t playing to the supposed studio audience or the people watching the panel, just interacting with each other. There’s less to prove.

Wherever it can, the show points to how the creative work of Asian communities in Aotearoa exists in relation to the audiences who consume that work, which largely means white audiences. The Showrunner says that she has to make her Asian sitcom a cultural product that is easy for “middle New Zealand” to consume, even if her writers long to be unpalatable. Both within the show and in its publicity, much is made of how it is the first Korean play produced by a mainstage theatre company with an all-Asian cast in Aotearoa. But the cameras, screens, and the presence of the audience are a reminder that representation means exposing yourself, and your community, to the people who don’t share your experiences.

“Presence is political,” says the Showrunner, trying to convince herself. I, too, want to believe this. I can’t escape my brown skin but I write for the majority white audience of The Spinoff. I’m here, and I’m Indian – but is that presence enough? Or am I simply another well-meaning writer whose only understanding of my own Asianness is, as another character says, in proximity to whiteness? Do I lose something when I write stories for white people, or do they gain something? Or do I invite a new audience?

The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom doesn’t want to answer these questions, because it knows there are no perfect answers. Consequently, the production feels unresolved – and it’s meant to. This lets it represent perhaps the most authentic experience of Asianness in Aotearoa: questioning how to exist in systems that both limit your identity and offer new ways to shape and share that identity. I can’t speak for all Asians in Aotearoa, and I don’t want to. But for myself and the possibility of challenging the institutions I’m part of, the show was a surprising yet welcome reminder that compelling creative work can exist within the unresolved questions.

The First Prime-Time Asian Sitcom runs at Q Theatre in Auckland until 27 November.