Sydney Theatre Company’s production of The Picture of Dorian Gray comes to Auckland Arts Festival on a wave of sell-out seasons and critical acclaim. Sam Brooks reviews.

On the face of it, a production of The Picture of Dorian Gray might not seem like an enticing one. You might not have read the book, and just be dimly aware of the vague concept: a vain man in Victorian England does not age, while a portrait of him in his attic does. You might be a huge fan, but have been burned by the many film and TV adaptations that do no justice to Oscar Wilde’s prose, let alone the transgressive, queer spirit of the novel. Thankfully, the version of The Picture of Dorian Gray coming to Auckland Arts Festival, courtesy of Sydney Theatre Company, is just about the best adaptation of the beloved novel that you could hope to see.

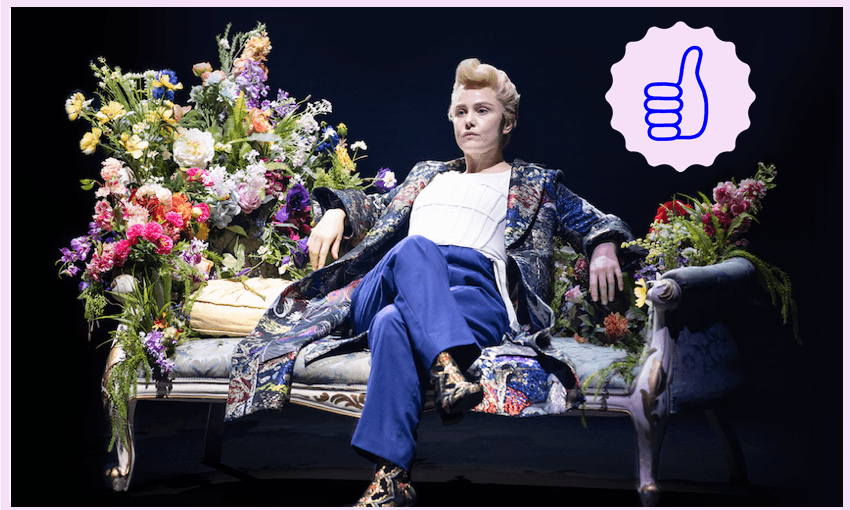

Sydney Theatre Company’s adaptation of the novel, courtesy of artistic director Kip Williams, is anything but austere. It revamps the novel as an energetic taut solo show with all roles played by the extraordinary Eryn Jean Norvill in a performance best described as Olympian. The production itself throws everything it can at the wall, and pretty much all of it sticks: Norvill is captured by a mixture of live and recorded video feed, which often overlap with each other and the physical performance onstage; projection is used to show the actor having a dinner party with several versions of herself; even miniature puppetry is employed to chaotic effect. It’s the kind of genre-bending joy that Wilde would have delighted in.

One of the best things about an arts festival, beyond getting to experience art that simply doesn’t exist in this country outside of that context, is getting to see a show that has run its paces and is as great as it’s ever going to be. There are always a few shows that are tried, tested and have gotten to the truth they’ve set out to accomplish. The Picture of Dorian Gray is one of those shows, coming off sell-out seasons and universal acclaim in Sydney. When it hits Auckland Arts Festival, it will be in its prime; all the kinks well and truly worked out, ready to be seen again and again.

Norwill gives the impression that she’s sprinting through the show – constantly in movement, constantly in flux between characters and cameras – but the reality is that she’s running a well-paced marathon. There’s no rush, no haste, just confident, brisk movement towards a confirmed destination. I’m used to seeing an actor in a solo show play multiple characters, throwing on vocal patterns and facial tics like bits of costume, but Eryn Jean Norvill does something truly extraordinary here. Think Jacob Rajan levels of extraordinary.

Throughout the show’s near two-hour runtime Norvill plays 26 characters, including sensitive artist Basil, hedonist playboy Lord Henry, lovelorn Sibyl Vane, and, of course, the titular Dorian Gray. Her characters can be defined bluntly, by a prop (Basil holds a paintbrush, Lord Henry a cigarette), or by something as subtle as the way she tilts her head and looks towards a certain camera. The skill needed to do this is gargantuan, to maintain perfect comic timing against yourself, but the depth of feeling and specificity she gives even the slightest of the 26 characters is what lingers. Her Dorian Gray isn’t a villain, but an aching pit of self-created need, wasting the youth and beauty he’s been inexplicably blessed with.

There’s a chance for a show like The Picture of Dorian Gray, where the technical elements are so interwoven into the performance, to come off as remote. Even as every screen brings the audience in closer to Norvill’s exquisite performance (which happens to be an asset in spaces that are as large as the ones this show is playing in), there’s a distancing effect. There’s a person acting their heart out in front of us, and we’re watching them through a screen instead. Of course, that remoteness is part of the point. The Picture of Dorian Gray is perhaps the greatest work of art about obsession with youth and beauty to ever exist, and that’s not warm and cuddly territory. That doesn’t make it a dour time – the show is witty as all hell, even gaggy at times – but it takes a while to settle in and realise that something that is achingly human is also, unfortunately, relatably human. I mean, what are selfies but our own reverse pictures of Dorian Gray?

It is easy to be won over by the spectacle of The Picture of Dorian Gray, there’s a lot of it. If you haven’t seen a big scale show since Covid-19, and even before, this might be the first time you’ll see one that incorporates live camera work at scale, and definitely the first time you’ll see it done this well. There’s nothing that matches up with spectacle, especially when it’s done with such assured brilliance. What you’re left with at the end, though, isn’t the spectacle. It’s the depth and breadth of Norwell’s performance, it’s the quiet moments when you can hear a pin drop in an audience of thousands, and the moments when a text reaches across a century, with the aid of a few screens, and hits you right in the chest. Unlike Dorian Gray, you probably still have a heart there.

The reviewer saw The Picture of Dorian Grey at the Roslyn Packer Theatre in Sydney. It plays at the Kiri Te Kanawa Centre as part of the Auckland Arts Festival from March 18 until March 25.