Music historian Gareth Shute watches When Bob Came, a documentary series which examines the cultural and societal impact of Bob Marley’s 1979 visit to Aotearoa.

Reggae is the biggest genre of local music in Aotearoa, both in terms of streaming numbers and live audiences at festivals. Many have traced this back to the concert that Bob Marley played at Western Springs in 1979. The six-part TVNZ series When Bob Came not only makes this case, but also takes a broader look at how his visit inspired other cultural and political movements in Aotearoa, while making Marley one of the most iconic and best-selling artists in our country’s history.

Fortunately, there’s a wealth of footage from Marley’s visit mostly due to the work of journalist Dylan Taite. Marley originally turned down all media requests, but as the first episode explains, Taite was aware that the singer and his band liked to play football – so he followed their movements with his own pair of boots in tow and managed to become a pick-up player when they decided to have a kick around.

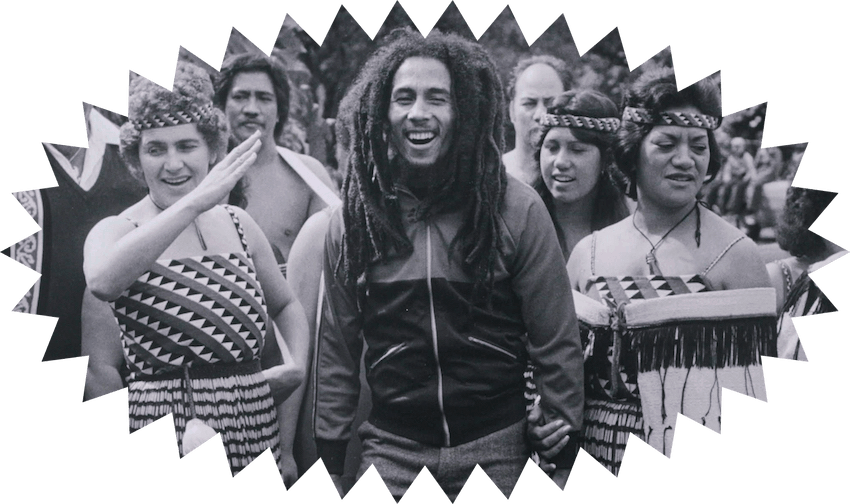

This connection led to a sit-down interview, which was one of few with Marley that is still accessible (his estate keeps tight restrictions on most others in existence). This may explain why excerpts from it have appeared everywhere from 2012’s Marley documentary to the outro of a Beastie Boys song (‘B-Boy Bouillabaisse: Dropping Names’). Taite’s piece also includes songs from the concert and a pōwhiri held to welcome Marley, which clearly blew him away.

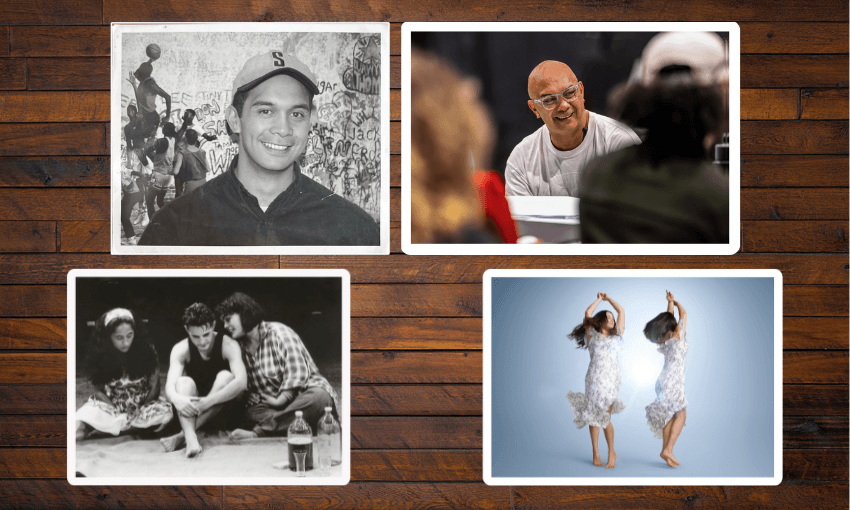

When Bob Came is able to recontextualise Taite’s footage by giving more of the back story of what else was going on in Aotearoa at the time (supplemented by other great archival footage) and then following the impact Marley’s visit had afterward. The show is presented by actor James Rolleston, whose engagement in the subject provides a lot more energy than would’ve been achieved with a dry documentary voice-over.

There are also interviews with a wide range of cultural icons, protest leaders and musicians. Some are from the local reggae scene, such as Tony Fonoti from Herbs and Tigi Ness, but many others come from outside it, such as Anika Moa, Melodownz, and SPYCC from SWIDT (though their biggest hit, ‘KELZ GARAGE’, is a reggae tune). Each has their own passionate explanation for the importance of Marley’s message of peace and standing up for one’s rights, including rasta musician Israel Starr’s claim that Marley was second only in influence to Jesus Christ.

The series begins with the concert itself and and the superlatives start flowing: those who were there were blown away; those who weren’t desperately wish they could’ve been there. In the second episode, the real purpose of the documentary becomes clear. Marley’s visit will be used as a prism through which to examine some of the changes in local culture in the years since his visit.

The most obvious place to start is the massive popularity of local reggae music. Members of our country’s first breakthrough reggae act, Herbs, were at the concert, so there’s a direct line that can be drawn. Yet, it’s a strain to fit the entire 40+ year history of local reggae into a single 23 minute episode, especially while also trying to continuously tie each iteration back to Marley’s influence. It ends up being playwright/filmmaker Oscar Kightley who best explains why reggae became more popular among Māori and Pasifika people:

“In country and western, it’s easy to sing about a broken heart … reggae lends itself to singing about broken systems.”

Next the series moves onto the rise of Māori and Pasifika protest movements from the 70s through to the present. Here the connection to Marley’s influence becomes slightly more tenuous, though there are points of contact. Che Fu recalls listening to Bob Marley’s music at the Takaparawhau (Bastion Point) occupation and his father Tigi Ness says that he found strength in Marley’s message while he was in prison for his part in the Springbok Tour protests.

It does seem crucial that Marley actually came here in person, while other overseas figures who inspired the local protest movement – like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X – never had the chance.

The series is on firmer ground when it looks at the Rasta religion and the history of marijuana in this country. Marley was a spirited advocate of both and there is plenty of material from the original Taite interview to tie into these themes. That said, When Bob Came leaves some threads left unpulled. For example, film director Tearepa Kahi talks on many interesting subjects, but never explains why he based his movie Mt Zion around a band trying to play support at the Bob Marley concert in 1979.

Yet these are just niggles about an overall absorbing series, which nicely captures how Marley arrived at the perfect time to feed his positive energy into struggles that were already going on in Aotearoa.

As Tearepa Kahi explains: “What Bob did, what Ngā Tamatoa did, what Whina has done for us is to keep the fires burning. Sometimes through generations the fires dim a little because we don’t have that collective voice or we lose sight of it because we’re all in survival mode. A lot of what we do today is in response to a sense of loss. That’s why art is so important, that is why story is so important, that is why music is so important – to keep those fires burning. Bob was definitely a part of that.”