Alex Casey reviews The Rule of Jenny Pen, a new local nightmare set within the four walls of a rest home.

Mortality and danger seep in from the very first scene of The Rule of Jenny Pen. As Judge Stefan Mortensen ONZM (Geoffrey Rush) squashes fly innards into his judge’s bench in the middle of a sentencing, we get the first of many warnings to anyone or anything who dares enter the film’s orbit: this is not going to be a painless ride, and not everyone is going to make it out alive.

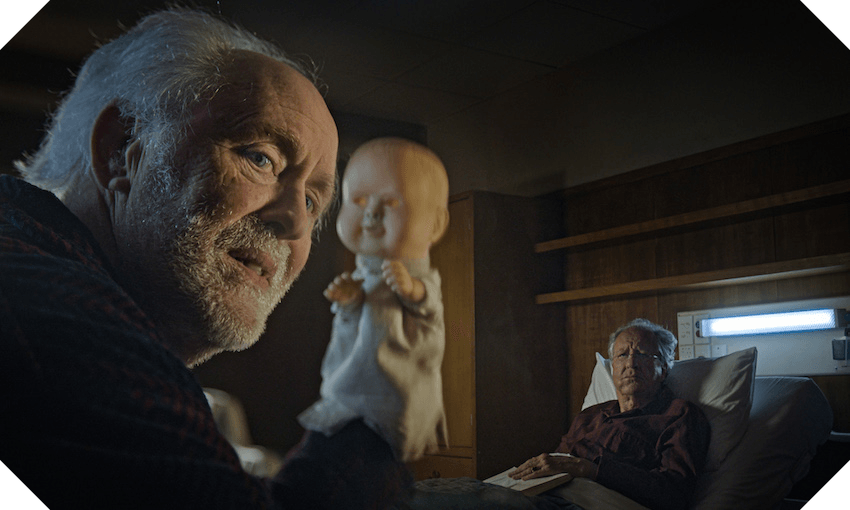

Nobody learns that better than Mortensen who, after suffering a debilitating stroke, finds himself out of the judge’s robes and into a shared room in an aged care facility. Directed by James Ashcroft and based on a short story by Owen Marshall, what transpires next is a cruel, claustrophobic and deeply disturbing ride, as Mortensen soon becomes the target of resident tormentor Dave Crealy (John Lithgow) and his creepy puppet called Jenny Pen.

Don’t let the marketing fool you – this is no run-of-the-mill Annabelle or Chucky joint about a dolly with a mean streak, but a relentless rumination on mortality, legacy and power. As Crealy creeps about the hallways taunting Mortensen and his roommate Tony Garfield (George Henare) in increasingly sadistic ways, the film asks a question far scarier than anything Slappy the Living Dummy could conjure: what if you encounter pure evil, but nobody believes you?

Once a pillar of society who professed “where there are no lions, hyenas rule”, Rush’s Mortensen is declawed and left at the mercy of Lithgow’s hyena, Crealy. Rush is exceptional as the cantankerous old curmudgeon thrown into a desperate situation, increasingly immobile but for the panic in his eyes. Joined by Garfield, a beloved former All Black, the pair represent some of the most respected positions held in New Zealand society, which makes it all the scarier when their autonomy is ripped away.

While Jenny Pen might be the cover girl, Lithgow is the monstrous heart of the film. He barely even speaks at first, icy blue eyes staring from afar with the disquieting presence of Michael Myers standing among in the linens in Halloween, or Lecter lingering in his cell. That stillness soon gives way to a terrifying physicality, whether it is him unleashing physical violence come nightfall or doing a chillingly spry jig in the middle of the day in the residents lounge.

(It’s also worth shouting out Lithgow’s New Zealand accent, one frequently so on-point that he even accurately pronounces the way an old racist white guy would mispronounce “meow-ri”.)

Also helping the creeping sense of dread are Ashcroft’s excruciating close-ups, slow zooms and disorienting camera angles. In Jenny Pen, action can play out in the reflection of a warped security mirror, or across a bustling room and through a window. Every choice makes audience feel more isolated and confused, sometimes obscuring a shot to just the tops of heads or the bottoms of legs, as if we will never get the full picture of what’s really happening.

It’s effective, if a little frustrating at times, and speaks to a few other murky aspects of the film. There are suggestions of some kind of supernatural presence, but these are never fully explored. As things unravel, we get hints about Crealy’s villain origin story, but not quite the full story. An early Final Destination-style sequence within the rest home sets the spectacle and shock bar admirably high, and I’m not sure the film ever quite reaches it again.

But perhaps a bit of ambiguity is the point here – Ashcroft told me himself he loves to dwell in the grey areas. The story gets a little muddled and repetitive towards the end, but so does Mortensen’s mental state, as conversations with specialists start to skip like CDs and his sense of time and place gets more and more distorted. The yawning long hallways, straight from The Shining, and flashing red smoke alarm lights certainly don’t make things anymore comfortable for anyone.

Just like Ashcroft’s first film Coming Home in the Dark, Jenny Pen goes all in on its bold and brutal vision without any of the wink-wink splatter-comedy schtick that New Zealand horror films often lean on for safety. Also like Coming Home, it cackles in the face of categorisation – this isn’t really a horror film at all, but thriller doesn’t feel right either. When menace looms in everything from an unattended bath, to a gate left ajar, it feels like a whole new kind of nightmare altogether.

The Rule of Jenny Pen is in cinemas nationwide from today.