Last week’s budget did include funding for the arts and culture sector – just not the arts and culture we’re used to seeing funded. And it’s long overdue, writes Sam Brooks.

There wasn’t a whole lot of arts and culture news in the 2023 budget last week. The government announced $1m in implementation costs for the artist resale royalty scheme, an $18m investment to build momentum of Matariki as a public holiday, and $2m for the Creative Careers programme, which teaches business skills to creatives.

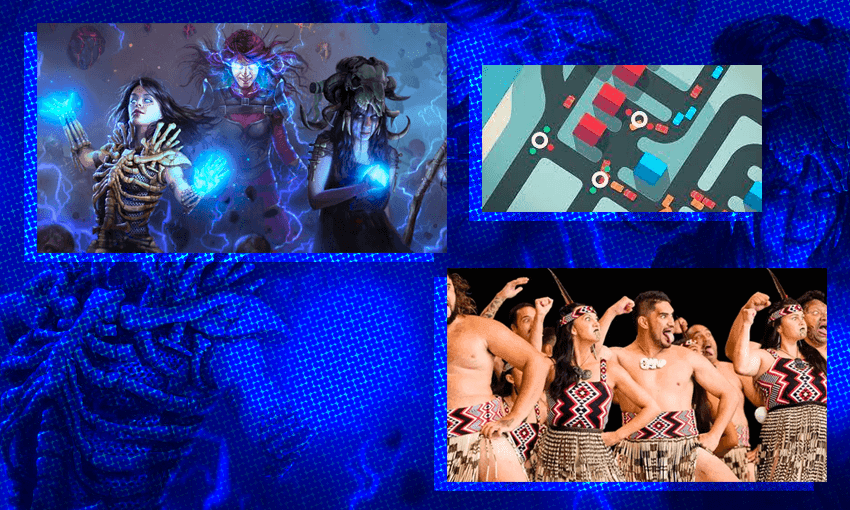

The big arts and culture winners, however, were Te Matatini and the gaming industry. Te Matatini, often described as “the Olympics of kapa haka”, has steadily increased in profile over its 51 years, with the festival held in Tāmaki Makaurau earlier this year drawing large audiences in person and on TV as well as generating a week’s worth of headlines, viral social media stories and international interest. The government set aside $34m for the organisation over the next two years to stimulate the growth of kapa haka, and enable it to expand its scope and role.

The budget also included a $160m investment over the next four years to introduce a tax rebate for the gaming sector. This follows calls from the industry for such a rebate, which is offered by countries like Australia and Canada, and means game development businesses (that meet the threshold of $250,000 in spend) can claim a 20% tax rebate, allowing each business to claim up to $3m.

At first glance, these might not seem like arts and culture investments. When arts and culture funding gets written about, it tends to be about the art forms that are historically assumed (from an outdated, western framework) to be worth calling art.

If you look at the arts organisations that get funding directly from the Ministry of Culture and Heritage, you see the likes of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra (roughly $15m annually) and the New Zealand Royal Ballet ($5m-6m annually). These investments are important, as is the recent $22m funding injection Creative New Zealand received to fund its general arts programmes and festivals around the country. Stuff’s coverage of the investments, for example, suggested that this budget “left artists in the dust”, without acknowledging that both Te Matatini and the gaming sector are built on the backs of artists and creatives.

In 2023, the public at large knows what art is, and what art is worth their time. It’s not just the ballet, it’s not just the orchestra, and it’s not just a painting in a gallery. It’s more than that. The nation, and the world, showed up in droves for Te Matatini this year. The world has had the work of New Zealand creatives in their pockets for decades thanks to gaming.

What these investments suggest is not just an increased government commitment to arts and culture, but an appreciation of what sectors contribute to the rich arts and culture of Aotearoa. But what does it mean to those receiving the funding?

Not only is it a massive increase for Te Matatini ($34m over two years compared to $2.9m), it’s timely. It recognises the festival at a crucial time for growth, capitalising on the immense reach it already has and supporting it to go bigger and wider. “It will contribute to our new vision Mana Motuhake ki te kainga: Matatū, Mataora, Matatini ki te ao,” he says. “That means that people in the rohe will decide who these funds will be distributed to which will include all the arts associated with kapa haka.” Seventy percent of the funding will go to supporting kapa haka in communities across the country outside of the biennial festival.

Ross is adamant that everyone who actively participates in kapa haka is an artist, and a creative, and this investment supports them. “That includes our kohanga reo, our primary and intermediate schools (Mana Kuratahi), secondary schools (Ngā Kapa Haka Tuarua o Aotearoa), our adults (pakeke) and kaumātua and kuia (Taikura Kapa Haka).”

Simply put, this investment funds the wider vision of Te Matatini: to support the growth of kapa haka nationally and globally.

According to Chelsea Rapp, the chairperson of the New Zealand Game Developers Association, the investment in the gaming industry is long overdue. “Without this incentive, New Zealand would have continued to create skilled graduates with creative ideas,” she says. “But the talent pool, investment and IP would have moved overseas.”

Rapp highlights not just the economic benefits of the gaming sector to the country, but the ubiquity of games as an artform. “Since the rise of the mobile phone, games have been everywhere that we are, and this will continue, with more of us spending time online and with advances in AI, the Metaverse and new media platforms.”

She believes this will present developers with an incredible opportunity to modernise the way that audiences view arts and culture “delivery”, highlighting the examples of games made here that showcase our culture to a global audience – Umurangi Generation, Guardian Maia, Toroa. “It’s important that New Zealanders own these narratives and be responsible for their guardianship, and that the government supports this, so that they are the ones to profit and not big US subsidiaries.”

Although the funding is welcome, it’s not perfect. The baseline for eligibility – that $250,000 threshold – excludes smaller developers, but Rapp believes this is by design. “It encourages studios to be ambitious,” she says. “The incentive is designed to help make NZ studios competitive in a global marketplace, and the baseline provides a space for studios to be aspirational.”

“This incentive is for the studios that want to build commercial success, create jobs, and ultimately contribute to New Zealand’s creative economy.”

The upper cap of $3m presents its own issues, potentially hindering the rate at which New Zealand can compete internationally. Rapp believes there will be pressure from investors to move to Australia because of their higher cap ($20m). “This cap tends to be unpopular politically but from an economic perspective it makes a lot of sense because it encourages studios to be ambitious.”

“This in turn attracts investors, publishers, and distributors to New Zealand, increasing the profitability and tax revenue of game studios nationwide.”

Again: the public knows what art is, and it shows up for it. What Budget 2023 has shown us is that the government is catching up to where the public is at, and spending public money accordingly.