Sickness, death and divorce – the Queens of the Stone Age frontman has seen it all in recent years. In his only New Zealand interview, he reveals how he survived.

The songs were written. The music was ready. By early 2021, Queens of the Stone Age had finished writing all the tracks for their eighth album. Toiling away in Homme’s now defunct Los Angeles studio Pink Duck, the five-piece desert-rock veterans had recorded an impressively fiery sonic blueprint. Raw, rowdy and real, everyone from guitarist Troy Van Leeuwen to drummer Jon Theodore realised it could be the best album Queens had made.

All they needed was their frontman to do what he does best and write lyrics that matched the intensity of the music they’d recorded. Then they could head out onto the road, do what they love to do and start touring again for the first time since 2017. “The guys were getting ready,” says Josh Homme. “They were on the razor’s edge.”

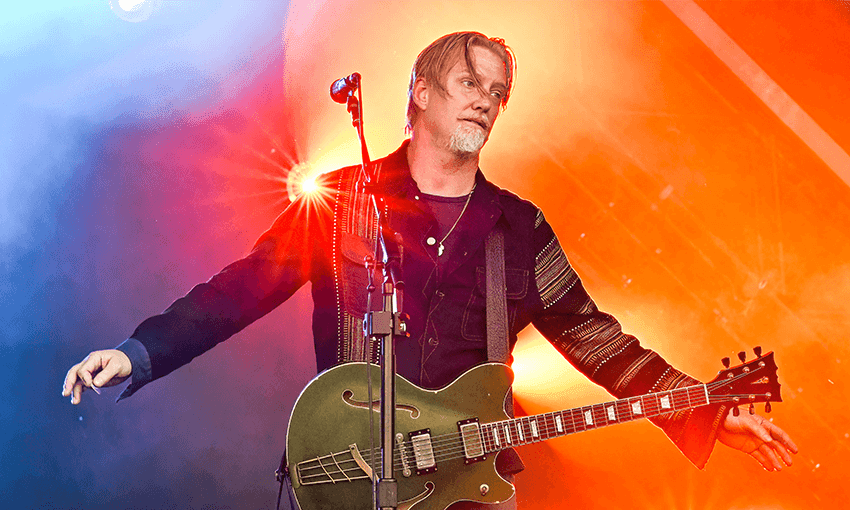

But those words just wouldn’t come to him. For the first time in his life, Homme, a statuesque front man with hip-swinging swagger, slicked-back locks and a classical baritone earning him the title of “The Ginger Elvis”, couldn’t put pen to paper. It felt too soon. “I don’t know if I was too terrified or just wasn’t through it all yet to start writing words,” he says.

He was stuck. The album went into limbo. “Maybe it was almost too personal. I thought I needed to get maybe get 10 or 20 paces back a little bit … There was too much going on.”

We’ve all trudged through some shit over the past few years, and Homme has had more than his fair share. Death, illness and divorce came knocking at his door. He answered in the only way he knew how: with silence. “I didn’t pick up the guitar for three-and-a-half years,” he says.

When coronavirus arrived, Homme was waiting. “When the world went into exile, I was already there,” he says. “I’d walk by my guitar and it would be like, ‘Hey’. I’d be like, ‘I can’t. Not right now. We’re friends, but not right now.’”

He didn’t play his guitar, and for the best part of two-and-a-half years, didn’t write a word either. His band’s songs sat there, frozen in time, waiting for him to be ready. Finally, in November, he felt like it was time to face what he was feeling. He got to work. “Fix your papers, throw out the trash, just chop wood and carry water,” is how he describes his attitude.

Doing the work meant the words came slowly at first, then all at once. When they started landing, they wouldn’t stop. “It’s a bit like a frozen waterfall,” he says. “You finally knock a piece away and the undercurrent all starts to flow and comes crashing down.”

The result is In Times New Roman, a record that vies with Songs For the Deaf and Era Vulgaris for the trophy of Best Queens of the Stone Age Album. To get there, Homme had to go through far more than he knew he was capable of. “Making this record felt like a very difficult blessing,” he says. “It’s been a long time … It was not easy to do.”

Before the new album’s release earlier this month, the last time anyone saw Josh Homme he was in tears. In Morgan Neville’s gruelling documentary Roadrunner, grieving friends of the globe-trotting food writer Anthony Bourdain give ultra-emotional interviews. Like everyone else, Homme’s captured at a time when he was dealing with the gulf left when Bourdain took his own life in a French hotel room in 2018. Harrowing is the only appropriate word to describe the film.

Has Homme seen it? “I couldn’t possibly,” he says. “Living through some of these things is enough.” It was one of many painful things he’s been dealing with. There’s been more death: new tattoos on his right arm mark the passing of the actor Rio Hackford, Foo Fighters drummer Taylor Hawkins and singer-songwriter Mark Lanegan, all close friends. There’s been the divorce from his wife Brody Dalle and his very public custody battle over their children to deal with. You can read the gossip columns to catch up on that one.

Then there’s cancer. Despite Revolver breaking the news that Homme had surgery last year to deal with an unspecified diagnosis, we’ve been instructed before the interview not to ask about his ordeal. “Josh is fine … it was a passing comment … he really doesn’t want to talk about it,” management warns. The only time he comes close to saying something about it is this: “I was a little bit unwell for a while. I had to focus on … you know … things about me, to heal.”

Like everything else that’s been going on in his life, it only adds to the concern fans have for Homme after after six years away. Is he OK? When he Zooms into view, he looks calm and relaxed. “I’m doing good,” he says from his Palm Desert home. The hum of family life – kids and barking dogs – can be heard in the background. The sun shines in through a window behind him so brightly he has to re-angle his camera to cut the glare. “I feel good.”

It’s no longer grey flecking his beard and goatee. Homme’s hair colour has gone from Gandalf the Grey to Gandalf the White, perhaps a reflection of what he’s been through. But there’s more to it than that. I’ve met Homme several times over the years. In 2010, we hung out back when Homme was touring with Dave Grohl and John Paul Jones in the rock supergroup Them Crooked Vultures. He was every inch the accommodating rock star, cracking jokes, ribbing Grohl, signing albums for fans, always the centre of attention.

This time, though, he’s different. Across our 30-minute conversation, he’s humble and heartfelt in one breath, then wistful and whimsical in the next. He hasn’t lost his knack for littering conversations with compelling visual metaphors – “The universe was made with friction, like the car crash of life,” he says about the creation process – but there’s an intensity to him that hasn’t been detectable before.

He admits he’s only doing a handful of interviews to promote In Times New Roman, and he’s only doing them because he feels like he’s created something important. Each record, he says, feels like “taking off one piece of armour and being a little bit more vulnerable”.

For this one, “I have no armour, I have only myself to give.” But he also says: “I think I’ve made something that says, where I’m at better than what I could say. I don’t want to ruin that sentiment by yammering on like a douche bag.”

On In Times New Roman, there is no yammering. It’s Queens’ most pointed, potent album yet. Musically, they nail that thing they do better than anyone, tricking you with one riff before delivering the real one. It’s visceral and alive, riffs stacking upon each other to create something more than the sum of its parts.

Over top of it all is Homme. His lyrics pine, howl and ache. “It’s become increasingly more about mining the vulnerable and terrifying sides of my life,” he says of his process. His words search for meaning, to find something, to land on an answer. “Use once and destroy / Single servings of pain / A dose of emotion sickness/ I just can’t shake / Then my fever broke,” he howls over the off-kilter riffs of Emotion Sickness.

What’s he looking for? Catharsis. “This is my religion, and my therapy, and my diary,” he tells me. It turned out he needed this album to help him make sense of what he was going through. “I needed the making of this to take it away,” he says. “That can be a really dangerous proposition because it puts a lot of pressure on what you’re doing.”

There are mistakes. It sounds like real-life humans are playing those instruments. Homme refused to correct things in the editing process: “Perfection is really boring,” he says. “If everything’s got rubber baby buggy bumpers on everything, it’s fucking safe. If it’s so safe, there’s no collision. I like the out-of-tuneness. I like the errors. I like the emotional rise. I want to exacerbate them. Then it starts getting good because it’s like, ‘Fuck, what’s happening?””

Queens have been regular New Zealand visitors, playing Big Day Outs, touring with the Smashing Pumpkins and Nine Inch Nails, and headlining their own tours. After everything he’s been through, is Homme ready to bring his new album, his mistakes, and his emotion sickness, to Aotearoa? Yes, they’ll be here, he confirms. He doesn’t say when, but admits: “When we don’t run the gamut of New Zealand it feels like we’ve made a mistake,” he says.