Don’t underestimate the significance of TVNZ’s new documentary series about Kai Kara-France, a fighter acclaimed on the world stage but still criminally underrated at home, writes Don Rowe.

In 2015, when I first profiled Kai Kara-France for the now-defunct Mana magazine, he told me he’d never wanted to sign with anyone but the UFC, mixed martial arts’ biggest stage. “I knew the day I started training when I was 15,” he said. “I’m definitely on the radar now.”

Seven years later, in July of last year, he was in Austin, Texas, fighting for a UFC belt against Mexican Brandon Moreno, the top flyweight (57kg/115lb) in the world. It was a journey that had taken Kara-France across the globe, fighting everywhere from a cruise ship anchored off the coast of Thailand to the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Three rounds into the fight, Kara-France was gaining momentum. Moreno was bleeding heavily from a cut beneath his eye and looked to be shying away from the Kiwi’s powerful strikes. After so many setbacks, so much adversity, Kara-France had one hand on the belt. And then, so quickly you could have missed it, Moreno fired a kick to the liver, dropping Kara-France and finishing the fight with punches on the ground. That’s where Caged, TVNZ’s new documentary series about Kai Kara-France begins.

The partnership itself is worth noting. It was only a few short years ago that combat sports in New Zealand were tolerated at best, but mostly spoken about with derision and disgust. Despite grassroots gyms producing international superstars, local fighters were lucky to get a mention in even the most regional of newspapers. The idea of MMA chat at the watercooler was about as likely as discussing the latest cockfight – which is what plenty of pundits liked to equate the sport with. That our state broadcaster would follow a fighter like Kai Kara-France, acclaimed on the world stage but still criminally underrated at home, is significant in itself.

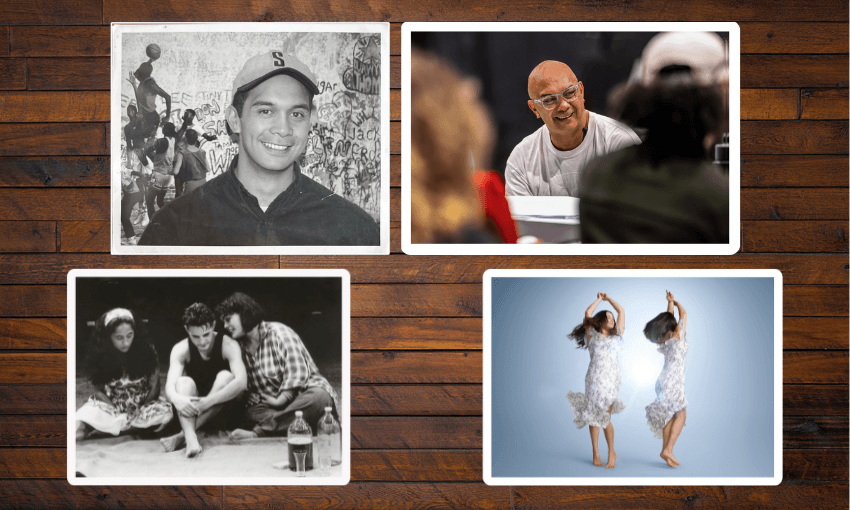

The scenes following Kara-France’s defeat give a brief glimpse into just what exactly has fuelled the shift in public sentiment towards MMA in Aotearoa. Backstage, Kara-France is consoled by teammates Israel Adesanya – our first true breakthrough athlete in the sport – and coaching doyen Eugene Bareman. Their recent success has catapulted MMA into the mainstream, undeniable proof of concept of the talent burgeoning here at home. But also there is Kara-France’s wife Chardae, his dad, and the teammates that Bareman credits with making his rise possible at all. Telling their stories, too, is where Caged shines.

Because MMA in this country has been built on the back of countless anonymous weekend warriors, filling YMCA halls, RSAs and pubs to support the local scene, month after month, with zero government support. As teammate John Vake says, when fighters like Kara-France started it was never about business, because there was no business. Caged shows the sacrifices not only of the fighters but their supporters too. Even at the highest level, training camps are all-consuming and the impact on other people in a fighter’s life are not often explored. As Chardae Kara-France says, “it’s a selfish sport”.

The UFC machine is famous itself for promoting the brand above the fighters, tightening their stranglehold on MMA, a grip that has seen the organisation face an ongoing antitrust lawsuit. Their marketing style guide is easy to summarise: nu-metal, flashing lights, self-serious proclamations about historical significance and, of course, Joe Rogan screaming.

But the company remains far and away the highest level of the sport, something like the NFL to American Football, or the PGA to golf. Making it to the UFC is the pinnacle of achievement for mixed martial artists, and while getting in the door is a lifetime achievement for most fighters, reaching the heights of a title shot is reserved for the truly elite like Kara-France. And while the UFC is rightly criticised for the pittance it pays to most athletes – around 20% of revenue is distributed to fighters in a given year – those at the top can make an impressive living. Kara-France’s success in the UFC has allowed him to buy his first home, start a family and branch out into his own clothing line, cognisant of the limited shelf-life of fighters in a sport where superstars routinely go broke.

Caged reflects the maturing of the martial arts scene in New Zealand, the changing public attitude around the sport, and Kai Kara-France himself. There is surprisingly little fight footage, but it takes you behind the curtain and sheds a light on the incredible locals involved in the highest levels of the sport. There’s still enough argy-bargy for the hardcores, and as a jaded and ageing MMA tragic, what I’ve seen only made me want to watch so much more.