Does the way science gets passed down through generations make it harder for girls to get into? And what can help change that? Alex Braae reports from the first day of the 9th International Conference on Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology.

Science has long been a bit of a boy’s club. That’s not a figure of speech either – as science knowledge gets transmitted, it has almost always been boys who have been the main beneficiaries.

The barriers to women being part of the scientific world have been both systemic and cultural, but they start early in life. Once upon a time, boys in the school system were formally funnelled into woodworking and metalworking, hard activities that required the learning of hard scientific or engineering knowledge. Girls did home economics, where they learnt the skills needed for a life as a wife and mother. Those days of formal separation are over now, but some cultural biases linger, as they’re passed on generation to generation.

Often that manifests itself in what happens in the home, over and above what happens in the school system. Traditionally, fathers would help their sons out with their science homework, or get them to help out with practical mechanical projects, and instil within them a love of scientific learning. There’s nothing wrong with that of course – it’s good for parents to be involved with the education of their kids. But does it really just have to be fathers and sons? And what are the mothers and daughters up to while that’s going on?

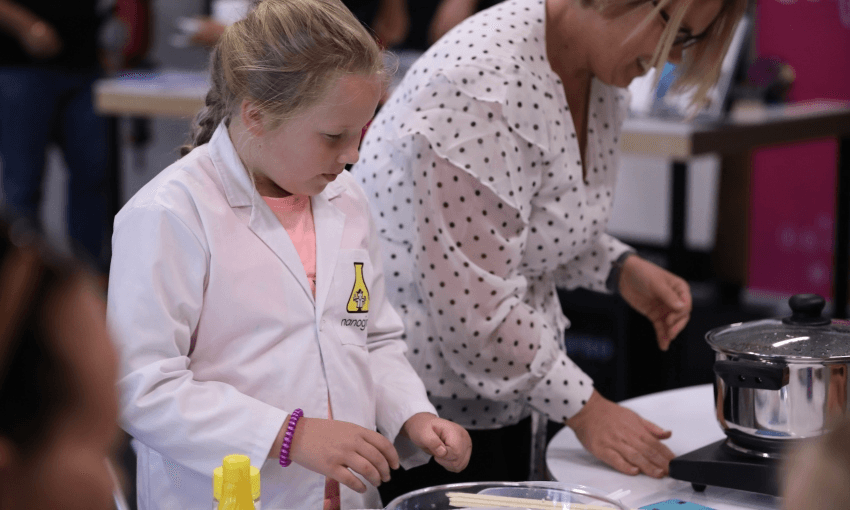

Some of them have been upending that, by heading along to a series of workshops being run at Te Papa, in Wellington. The workshops are hosted by Dr Michelle Dickinson, perhaps more well known to the world as the science communication superhero Nanogirl. They’re among the events aimed at the public being put on for the Macdiarmid Institute’s AMN9 conference, and are in some ways a clever subversion of the old Home Economics classes. There’s a cookbook for mothers and daughters to work from, but it’s a cookbook full of science experiments.

Dr Dickinson says one of the major problems she’s seen with mothers is that they weren’t confident about science during their own childhoods, and have never had the change to learn that confidence as adults. “We do home economics, and we do science, we say one is academic and the other is a vocation. And at no point do we say they’re actually based on the same things.” She says her Kitchen Science cookbook has empowered a lot of parents – but especially a lot of mothers – to start doing science experiments with their kids.

The kids have a whale of the time in the workshops too. One of the experiments involves a spoon with a piece of string wrapped around it, which is then dinged by another spoon – the experiment demonstrates how sound waves travel and are conducted. The girls wrap the end of the string around their fingers, and stick them in their ears, so that the sound of metal on metal sounds deep and resonant, like a gong. One girls face lights up in absolute delight, and Dr Dickinson notices. “I love that face,” she says. “That’s the face of science.”

Associate Professor Nicola Gaston, a University of Auckland physicist who is a co-director of the MacDiarmid Institute, says public events are a crucial part of why the organisation bothers to organise big international conferences in the first place. “Because we’re bringing exciting international researchers to New Zealand, there’s always a sense that we want to share what they’re doing with New Zealanders.” Having events aimed specifically at kids is a bit newer, but something that is happening more, because “it supports people to think of science as being for them.”

Dr Gaston says that events that bring mothers and daughters together aren’t about excluding boys. “It’s just to be really straightforward about the fact that kids often see science as something that is male dominated, and therefore for boys. It’s not the kids fault, what they think sometimes. But having kid focused events helps change that, at an earlier stage.”

But she says the challenge of overcoming those biases will take a long time, and it’s still very early to say if explicit efforts like this are having an effect. Dr Gaston says unconscious biases still matter enormously in how people see the world, and while there are more women in science than there used to be, changing those attitudes isn’t automatic. “Culture perpetuates itself, by default. You can look at some of the studies that have been done on unconscious bias, and they look dramatic and scary, and they’re reflecting back the attitudes of our grandparents. But then you look at the participants in these studies, and they tend to be college students. And kids perhaps reflect back most naively their perceptions of society.”

Dr Dickinson says she sees these unconscious biases being passed on all the time, and that’s one of the reasons why she does what she does. “A lot of parents transfer their fears to their kids. Maths is a great example – parents say I wasn’t good at maths at school, so it’s okay that you’re not.” And she says that can often be gendered, with mothers making that excuse for their daughters. “We wanted to prevent that generational fear, which we were seeing lots of.”

Some parents, of course, don’t want the old gender norms to be part of their kids’ lives. Katie Evans is one of the mothers who brought their daughters along to the Science Kitchen event. She did home economics at school, and sometimes wonders what could have happened if other things had been encouraged. Her daughter wants to be an astrophysicist (she’s 8 years old, and turned up in a lab-coat) and so the family have always backed that passion. Her daughter’s aptitude and interest in science was noticed by her school, and she was given the opportunity to go up to the next syndicate, because there was a really science focused teacher there. “A teacher did recognise that keenness for science in her, and so gave her that opportunity. Everyone was really grateful for that.” But she says it’s a concern that for a lot of kids, their interest won’t be noticed in an education system that has to try and get everyone through.

So is the goal of these workshops to create a whole new generation of women who are scientists? Not necessarily, says Dr Dickinson. Rather, the best outcome would be a population full of people who are confident in knowing how science works, and how it can be used. Even if it doesn’t result in more people having careers in science, it would still make the world a better place. She cites the snake oil she sees some people who don’t understand science get sucked into buying, as an example. “We’re bombarded by celebrities selling us potions and lotions, with names of things that are made up, and I just want people to be able to evaluate things, because they’re not intimidated by the long words, and know how things work. Or if they don’t they can figure out how to find that information.”

“I want them to be able to make scientific decisions,” she says. “I want to make choices for me and my children that are based on evidence – a scientifically literate society. And who knows where the next great invention will come from, if we have a scientific and engineering mindset?” Those great breakthroughs become much more likely when half the population doesn’t feel excluded from birth.

This content was created in paid partnership with the MacDiarmid Institute. Learn more about our partnerships here.