And can you spread it before symptoms start? Epidemiology expert C Raina MacIntyre on what we know so far.

Cases of the Wuhan coronavirus have increased dramatically over the past week, prompting concerns about how contagious the virus is and how it spreads.

According to the World Health Organisation, 16-21% of people with the virus in China became severely ill and 2-3% of those infected have died.

A key factor that influences transmission is whether the virus can spread in the absence of symptoms – either during the incubation period (the days before people become visibly ill) or in people who never get sick.

On Sunday, Chinese officials said transmission had occurred during the incubation period.

So what does the evidence tell us so far?

Can you transmit it before you get symptoms?

Influenza is the classic example of a virus that can spread when people have no symptoms at all.

In contrast, people with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) only spread the virus when they had symptoms.

No published scientific data are available to support China’s claim transmission of the Wuhan coronavirus occurred during the incubation period.

However, one study published in the Lancet medical journal showed children may be shedding (or transmitting) the virus while asymptomatic. The researchers found one child in an infected family had no symptoms but a chest CT scan revealed he had pneumonia and his test for the virus came back positive.

This is different to transmission in the incubation period, as the child never got ill, but it suggests it’s possible for children and young people to be infectious without having any symptoms.

This is a concern because if someone gets sick, you want to be able to identify them and track their contacts. If someone transmits the virus but never gets sick, they may not be on the radar at all.

It also makes airport screening less useful because people who are infectious but don’t have symptoms would not be detected.

How infectious is it?

The Wuhan coronavirus epidemic began when people exposed to an unknown source at a seafood market in Wuhan began falling ill in early December.

Cases remained below 50 to 60 in total until around January 20, when numbers surged. There have now been more than 4,500 cases – mostly in China – and 106 deaths.

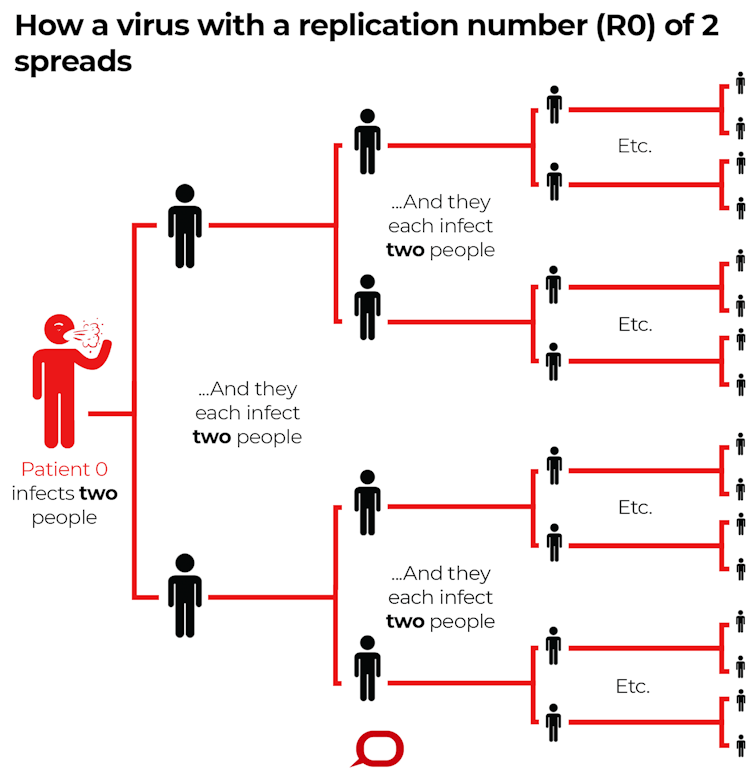

Researchers and public health officials determine how contagious a virus is by calculating a reproduction number, or R0. The R0 is the average number of other people that one infected person will infect, in a completely non-immune population.

Different experts have estimated the R0 of the Wuhan coronavirus is anywhere from 1.4 to over five, however the World Health Organisation believes the RO is between 1.4 and 2.5.

Here’s how a virus with a R0 of two spreads:

If the R0 was higher than 2-3, we should have seen more cases globally by mid January, given Wuhan is a travel and trade hub of 11 million people.

How is it transmitted?

Of the person-to-person modes of transmission, we fear respiratory transmission the most, because infections spread most rapidly this way.

Two kinds of respiratory transmission are through large droplets, which is thought to be short-range, and airborne transmission on much smaller particles over longer distances. Airborne transmission is the most difficult to control.

SARS was considered to be transmitted by contact and over short distances by droplets but can also be transmitted through smaller aerosols over long distances. In Hong Kong, infection was transmitted from one floor of a building to the next.

Initially, most cases of the Wuhan coronavirus were assumed to be from an animal source, localised to the seafood market in Wuhan.

We now know it can spread from person to person in some cases. The Chinese government announced it can be spread by touching and contact. We don’t know how much transmission is person to person, but we have some clues.

Coronaviruses are respiratory viruses, so they can be found in the nose, throat and lungs.

The amount of Wuhan coronavirus appears to be higher in the lungs than in the nose or throat. If the virus in the lungs is expelled, it could possibly be spread via fine, airborne particles, which are inhaled into the lungs of the recipient.

How did the virus spread so rapidly?

The continuing surge of cases in China since January 18 – despite the lockdowns, extended holidays, travel bans and banning of the wildlife trade – could be explained by several factors, or a combination of:

- increased travel for New Year, resulting in the spread of cases around China and globally. Travel is a major factor in the spread of infections

- asymptomatic transmissions through children and young people. Such transmissions would not be detected by contact tracing because health authorities can only identify contacts of people who are visibly ill

- increased detection, testing and reporting of cases. There has been increased capacity for this by doctors and nurses coming in from all over China to help with the response in Wuhan

- substantial person-to-person transmission

- continued environmental or animal exposure to a source of infection.

However, with an incubation period as short as one to two days, if the Wuhan coronavirus was highly contagious, we would expect to already have seen widespread transmission or outbreaks in other countries.

Rather, the increase in transmission is likely due to a combination of the factors above, to different degrees. The situation is changing daily, and we need to analyse the transmission data as it becomes available.![]()

C Raina MacIntyre is Professor of Global Biosecurity, NHMRC Principal Research Fellow, Head, Biosecurity Program, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.