Body Mass Index (BMI) is particularly flawed as an indicator of health in children and ethnic minorities. So why do we still use it?

In a new comment piece published in the New Zealand Medical Journal, registered dietician Lucy Carey argues that the use of the Body Mass Index in assessing children’s health is both a flawed measure and potentially harmful.

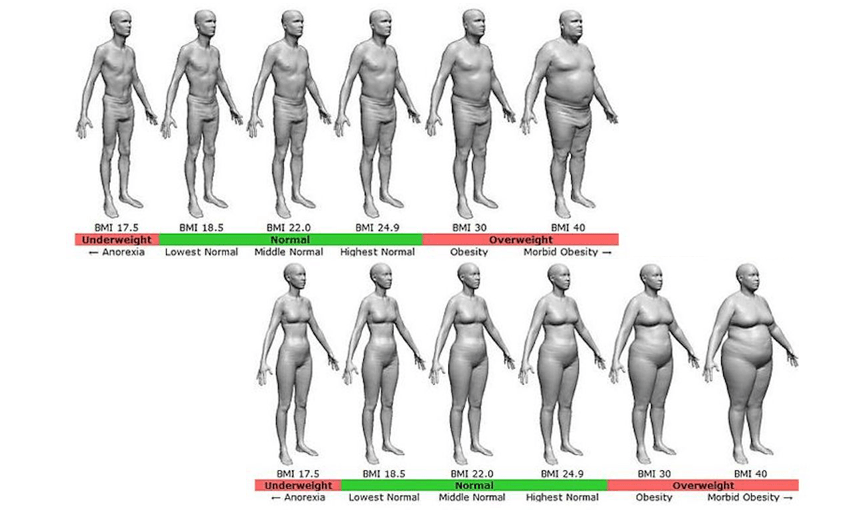

Body Mass Index, or BMI, is used by doctors and health practitioners to estimate the level of fat in a person’s body, thereby assessing their risk for some diseases and thereby assessing their health. A person’s BMI percentage is found by taking a person’s height squared and dividing it by their weight. BMI is how many kilograms per metre squared. No other data points are used.

There are four categories: underweight, healthy weight, overweight, obese.

The test is included in the B4 School Check, a health check for all four-year-olds in New Zealand to identify any areas of concerns before a child starts school.

With a category officially labelled “healthy weight”, one would assume the other three categories represent an unhealthy weight. And so begins the long list of problems with BMI as an indicator of health. By using the test so early, young children are being diagnosed as overweight and obese, spurring their parents into action in order to help their child lose weight. But Carey argues this often has an inverse effect on the child’s weight. “One hypothesis is that this is because parents restrict their child’s food intake, thereby creating feelings of deprivation and food obsession.”

Assessing a child’s health while factoring in their weight is not the issue. The use of labels and the focus on size over wellbeing is. “Every family, regardless of the size of their child, could have a conversation with the health professional about healthy living,” writes Carey. “In this way, a problem-focused approach becomes solution-focused.”

As well as being an inconsistent (at best) indicator of health in children, BMI has proven to be a frequently ineffective indicator of health for Māori, Pacific, and Asian people. AUT associate professor Scott Duncan argued in 2017 that Māori and Pacific people were being overclassified as overweight while Asian populations were being underclassified as overweight. Māori and Pacific people are “heavier in general; they have more lean muscle mass, as well as having bigger frames.”

Using an online BMI calculator and being classified as overweight (and therefore unhealthy) may have little effect on some people and their actions. But BMI is used by doctors when assessing next steps in a patient’s health journey and it’s used by adoption agencies as well (did you know you can’t adopt a baby from China if your BMI is over 40?) It’s used in part to prioritise potential beneficiaries of subsidised reproductive technologies. And it’s used by insurers when calculating health insurance premiums. It’s not just a fun online tool that can be ignored by those it miscategorises.

And it does miscategorise. BMI doesn’t distinguish between muscle mass and fat mass. Muscle weighs a lot more than fat so a person with high muscle mass will weigh significantly more than someone of the same size but with little muscle mass. In other words, every All Black is overweight or obese and most people who go to the gym for anything but cardio will register a higher-than-average BMI.

And finally, labels. Overweight and obese have negative connotations and send out an inherent signal that something must be improved. In many cases, losing weight will improve future health outcomes, but it’s far from the only factor. More recent research has shown that being overweight does not always mean lower health outcomes, just as being a ‘healthy’ weight does not always mean that someone is actually healthy. We all know someone who hasn’t eaten a vegetable in ten years but remains skinny. No one would argue that they’re the pinnacle of health.

Young people, particularly women, are bombarded with images of skinny, often unhealthy, body images and told that that’s the ideal. To be labelled overweight or obese can lead to drastic action, especially if miscategorised.

To give a real-life example, below is my BMI from last year as calculated by a tool on the NZ Heart Foundation website. The image on the left is what I looked like after a few months of a training and health bootcamp. On the right is my BMI calculation according to my height and weight that day.

A BMI of 25.1 is on the very low end of the ‘overweight’ range, but that’s not noted in the result. And someone worried about their weight wouldn’t take much comfort in that anyway. I don’t care much about BMI. I’ve never been close to the middle of the “healthy weight” range, even when I’m at my most athletic and healthiest. I’m always significantly heavier than women who look the same size as me (I don’t know why). It scares me to think that myself in that picture could lose 19kg and still be classified as “healthy”.

As of two days ago, according to my new BMI, I’m no longer overweight – I’m obese. Even though I know that my blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar are all very good, and that I’ve also put on muscle, I exercise, and I do the things healthy people are supposed to do, it’s hard to look at “very unhealthy weight” on an online BMI calculator without worrying.

As one of the few universal ‘indicators of health’, BMI influences a lot of people’s decisions around their weight and lifestyle choices despite being a deeply flawed measure of health, particularly for ethnic minorities and children.

The flaws of BMI are debated regularly by researchers and doctors, and yet it’s still being used by health practitioners around the country, even on children as young as four years old. Carey suggests getting rid of BMI entirely when assessing children’s health, and replacing it with discussions with all parents about healthy choices.

“The talking points are mainly self-reported and subjective, and they are less simply measured than BMI,” she wrote. “But they are also far more meaningful in everyday life.”