The more hard surfaces we build, the more stormwater we need to drain. Here’s how we can future-proof our urban design as climate change bites.

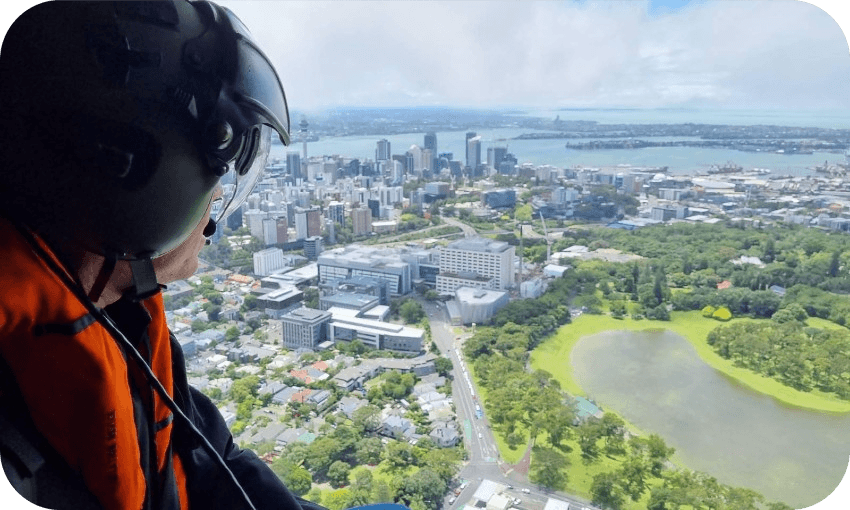

We’ve built our cities to be vulnerable to – and exacerbate – major weather events such as the one we saw in Auckland on Friday. While almost no city in the world could fully escape the effects of four months’ worth of rain in 24 hours, there are many things that could have been done to avoid some of the worst impacts.

Buildings, streets and car parks are all impermeable surfaces. When it rains, the water rushes off these surfaces and into gutters. From the gutters, the water drains into a stormwater catch basin, through the stormwater network, and into streams and the sea.

Herein lies the problem. The more we build, the more stormwater we need to drain. Every new building or road replaces the planet’s natural stormwater system: plants and soil, and channels for runoff.

The network of pipes can only hold so much water before it is fully inundated and begins to flood. While every block typically has a catch basin or two, they can easily clog with leaves and other debris even before a storm hits. Add an abnormal amount of rainfall, and neighbourhood flooding is nearly guaranteed.

Flooding and contamination

Even if the way we’ve built our cities and the stormwater system could keep up with big storm events – to be clear, they cannot – the network of basins and pipes is aging. With age, the system’s capacity to capture stormwater significantly declines.

Modernising all the stormwater infrastructure will take decades and billions of dollars. This is what the contested Three Waters project is really all about, and we need to quickly get past the political sideshows it has inspired.

While the system ages and suffers from reduced capacity, it is also more prone to failure. It’s not uncommon to see news that stormwater has mixed with raw sewage. This is gross just to think about, but it gets worse.

Because stormwater is not treated, when it gets contaminated that dirty mixture drains into the water around our beaches. It’s why, after a storm, the SafeSwim map is covered in red “high risk” markers.

Roads become rivers

From Friday’s rain event, some of the most shocking images were of cars and buses trying to wade through flooded roads and busways. The irony is that the roads themselves are a significant contributor to the flooding.

With thousands of miles of sealed roads around Auckland, there was simply nowhere for the water to go. Roads act like channels, funnelling stormwater. With a huge rain event, streets quickly turn into rivers.

Setting aside the concoction of stormwater and raw sewage flowing down streets (which we more politely call a “combined sewer overflow”), and the impact on homes, businesses and beaches, flood waters also present a massive risk to people in cars.

It’s nearly impossible to tell how deep or fast surface flooding is, so people get into danger.

The ‘sponge city’

There is a better way to design our built environment. In the early 2000s, Chinese architect Kongjian Yu created the concept of the “sponge city”. It’s a relatively simple idea, but a big departure from the way we typically build infrastructure.

The concept incorporates green roofs, rain gardens and permeable pavements to absorb and filter water. Better catch systems hold rainwater where possible and reuse it. More green space and trees are also incorporated into street and neighbourhood designs.

Within the sponge city concept is a way to mitigate flooding using “water sensitive urban design”. With this approach, we create spaces that better manage flooding through systems that mimic the natural water cycle.

This can also include floodable infrastructure and parks to take the pressure off more vulnerable parts of the city. There are already examples of these design principles in Auckland, but they are far too limited to eliminate the impact of major storms.

Building smarter

The sponge city concept, and ideas about letting nature handle stormwater, don’t have to be extravagant or expensive. They can be as simple as planting more trees and greenery, using less pavement for driveways or more porous cement for car parks.

In a way, we should do less building and let nature do what it was meant to do.

The stark reality is the flooding we experienced this week, and arguably the storm itself, are of our own making. We’ve built a supercity covered in impervious surfaces, expanded the built environment across sensitive (and flood-prone) areas, and created massive greenhouse gas emissions destabilising the climate.

Climate change will make future storms more intense and more frequent. Do we cross our fingers and hope the rain goes away? Do we invest billions in bigger pipes that will inevitably fail to control flooding and still pollute sensitive waters? Or do we get smarter and more proactive about designing our cities?

If we don’t want to repeat the week’s events, there’s only one real option.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.