As officials warn travellers into New Zealand may have been exposed to measles this month, health experts are worried about our declining vaccination rates. Here’s why.

Experts have warned that gaps in New Zealand’s vaccination rates could open the door for a deadly measles outbreak.

The warning comes as health officials have this week called for people who travelled on some international flights to come forward due to the possibility they may have been exposed to the disease.

According to the latest data, immunisation rates for children have dropped to the lowest levels in 15 years, and are particularly low among Māori and Pasifika. It’s something that could have major implications the next time measles does make it into the community.

It’s not unforeseeable, either. Recent outbreaks have caused severe illness and deaths in New Zealand and the wider Pacific. In 2019, New Zealand experienced its worst measles epidemic since 1938, with over 2,000 confirmed cases, hundreds hospitalised and two deaths. In the same year, a widespread outbreak in Sāmoa killed 83 people.

In short, as Nikki Turner, medical director of the Immunisation Advisory Centre, explained to The Spinoff, measles is “way more” infectious than Covid-19. “If you stood in the far corner of a room and I had measles, I’d give it to you. It’s incredibly infectious,” said Turner. “It will spread through a community like wildfire, and what will stop it spreading is if the community has got immunity either from having the disease while they were younger or being vaccinated.”

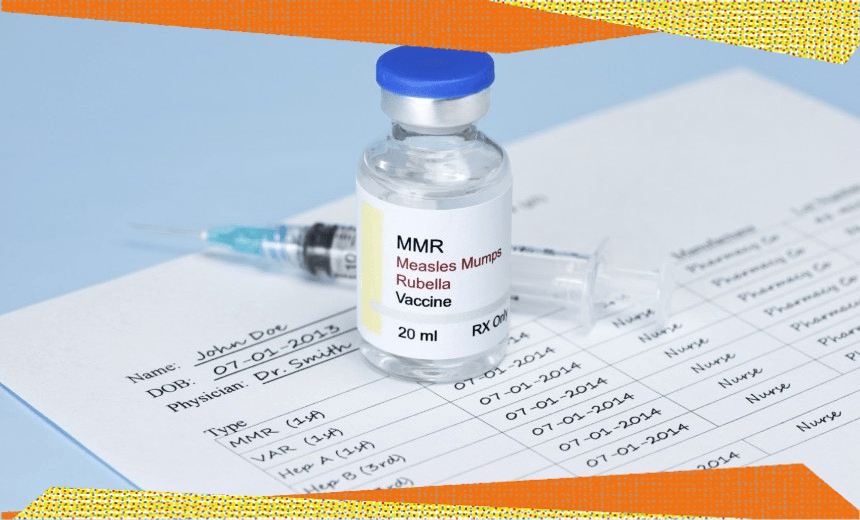

A measles vaccination has been part of the routine immunisation schedule in New Zealand since 1969. Two doses of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine is 99% effective at preventing measles – children should receive their first at 12 months of age and their second at 15 months. Anyone born after 1969 who may have missed getting their two doses in early childhood can catch up at any time. Adults born before 1969 are considered immune to measles – the infectious nature of the disease and the fact a vaccine wasn’t available in New Zealand until this date means people born earlier were probably already exposed.

In a Public Health Communication Centre (PHCC) briefing co-authored with Turner and several others and released earlier this week, prominent public health physician Michael Baker warned that New Zealand was on the brink of a major measles outbreak. Overall vaccine coverage for two-year-olds is now at 83%, and that rate is much lower for Māori children (69%), Pacific children (81%) and children living in the most deprived neighbourhoods (75%). “These levels are far below the 95% target level needed to maintain measles elimination,” the briefing said.

Data shows that New Zealand’s immunisation rates were tracking up until about 2018. Then, two years later, Covid-19 arrived in the country and uptake dropped off significantly amid lockdowns and a health system in pandemic mode.

“What we’re developing across our country is gaps in the protective immunity… and we’re seeing a resurgence of measles internationally alongside a resurgence of people travelling,” said Turner. “So we will see measles again in New Zealand… and we are at high risk, not of just seeing measles but of it being able to spread in the community.”

The PHCC briefing called for a number of urgent actions to prevent the future spread of measles, including bolstering vaccine uptake – especially among groups most at risk – and addressing immunity gaps by focusing on catch-up immunisation for children and young people, with the priority in early childhood education centres, schools and other institutions where many people mix.

The government has already announced plans to encourage this. In December last year, new health minister Shane Reti announced a $50 million package targeted at raising immunisation rates. Of that funding, $30 million will go to Whānau Ora providers to work with those most at risk – including Māori – while an additional $10 million will go to North Island partners and $10 million to South Island partners.

While in opposition, National promised to give GP clinics a one-off payment of $10 per enrolled patient on their books, provided they lift childhood immunisations, MMR vaccinations and flu shots by 5% among eligible patients before June 30, 2024.

In late January, Reti told RNZ the threat of measles was concerning. “Our herd immunity target is 95% so you can see the distance of where we need to be [to ensure] a degree of comfort around how we might be collectively protected in an outbreak,” he said. Setting this target was part of the coalition government’s 100-day plan, but meeting that target would take much longer.

“I’m becoming increasingly anxious as I look at the outbreaks in the UK and the US, and seeing experienced colleagues like Michael [Baker] say he is certain that we’ll have a measles outbreak this year,” Reti said.

There is no single reason why immunisation rates have dropped but Turner said, “Part of the issue, clearly, is there was a kickback of people disliking mandates and Covid [vaccines]. There was a lot of confusion through Covid and a lot of people are worn out with vaccines and vaccine issues.”

Social media hasn’t helped, added Turner, and can “scare people” away from being vaccinated. The importance of reliable information was highlighted in recent University of Auckland research that found people most valued being given information about possible adverse effects from vaccines and how much protection would be offered for how long. Vaccine origin and route of administration were the least important. Meanwhile, further research out of AUT this week focused on the efficacy of vaccine mandates concluded that requiring people to be vaccinated during the Covid-19 pandemic could lead to “lower voluntary vaccine uptake” in the future.

But, said Turner, it wasn’t just people’s concerns about vaccination that may stop them from being immunised. Some groups – especially in Māori and Pasifika communities – may lack easy access to health services or primary care providers. For example, if people aren’t working regular office hours, it can be difficult to access healthcare without travelling. “A lot of people may not be enrolled with a regular practice, and some don’t have a trusting relationship with a primary care provider,” Turner said.

Turner felt the government initiatives announced so far were a positive step.

But Dr Mamaeroa David, a GP and senior Māori adviser at the Immunisation Advisory Centre, and a co-author of the briefing with Baker and Turner, told The Spinoff that throwing money at the issue was not enough.

“As a GP, I don’t have any extra time no matter how much extra money you chuck at me… The reality of it is we need to expand systems and think about a long-term sustainable approach that actually improves the vaccination systems that are in place,” she said.

“The biggest elephant in the room is that our GPs are under a lot of pressure, it’s very difficult to get an appointment. Our clinic has had its books closed for the past year and that was because it was just overwhelming having new enrolments flooding in… we have to look after our staff and we can only do as much as we can do, as well as not having three- or four-week waiting times for a GP appointment.”

And with vaccination rates for Māori children so worryingly low, David said the government’s decision to disestablish Te Aka Whai Ora, the Māori Health Authority, was “heartbreaking” and may result in rates declining further. A health authority having “tino rangatiratanga to be providing a healthcare approach that is kaupapa Māori” was crucial, she said, and should have been given more than 18 months to prove itself.

Reti, in announcing his immunisation rates-targeted package last year, said he believed at-risk communities would benefit. “The new funding will play a vital role in helping Māori health providers better reach out into their communities,” Reti said. He has repeatedly defended his government’s decision to dismantle Te Aka Whai Ora, saying it will enable decisions to be made closer to the community. “Local circumstances require local solutions rather than national bureaucracies,” Reti said this week.