The secret to a long and happy marriage? Bizarre Bras.

Erna Van Der Wat was out for dinner with her husband Karl when inspiration struck. She was fiddling with a bundle of straws on the table, twisting them around her hand, when she unearthed her next big World of Wearable Art project. “I held up the straws and I looked at Karl and I said ‘this is what I want’,” she laughs over the phone. Months of trial and error with aluminium tubing followed, resulting in a garment that weighed about 18kg when it eventually debuted on the WoW runway in Wellington.

As the model made her way down the stage wearing the piece – ‘Reflections’ – a civil engineer leaned over and asked the Karaka couple how on earth they managed to get the heavy tubing to stick together like that. Karl laughed and answered his question with another question.

“Have you ever heard of Super Glue?”

Property developers by day, the Van Der Wats have been “pulling the sleigh” of marriage together for over 30 years and entering the iconic World of Wearable Art competition since 2006. Erna remembers the moment that WoW entered her life very clearly – she was watching TVNZ’s Good Morning in 2006 when a clip came up from the show. “I just thought ‘Oh my gosh, this looks really really lovely’. And then I just entered, stupidly not knowing what I was getting myself into.” She had always dreamed of making costumes for theatre, but followed her parents’ advice to “get something behind your name first”.

Her first entry was a piece called ‘Intrigued’ in the Illumination category, where models walk under UV lights against a black backdrop. “It was basically just three wooden triangles and white elastic,” Erna says. “It was simple, very simple.” As simple as her entry was, it was the elaborate showcase it featured in that got her husband Karl, a former ostrich farmer who previously thought WoW was “crazy”, intrigued to start creating alongside her. “There’s that old saying that if you can’t fight them, join them,” he laughs.

They joined forces in 2007, entering the infamous Bizarre Bra category with ‘A Pair of Good Lookers’. “That was a really nice one,” remembers Erna. “It was two eyes and the eyelids actually opened and closed and she had these beautiful long lashes and it was all made out of beads.” They still display it in their lounge to this day, alongside the other Bizarre Bras they’ve made through the years, including one made out of copper and old trophies and another that resembles a giant pair of spectacles.

Storage is an enormous problem for WoW-heads, and the Van Der Wats have had to kill some of their darlings over the years to stop their home being taken over by enormous and elaborate garments. “There was an entry that I sent in one year that I knew was not even going to make the show,” says Erna. “My heart was so broken when they sent it back that we poured a glass of wine, took the chainsaw, and we cut it up into pieces.” Karl remembers struggling to get the piece, titled ‘Stairway to Heaven’, out of the house in the first place. “No courier wanted to touch it – we probably needed a space shuttle.”

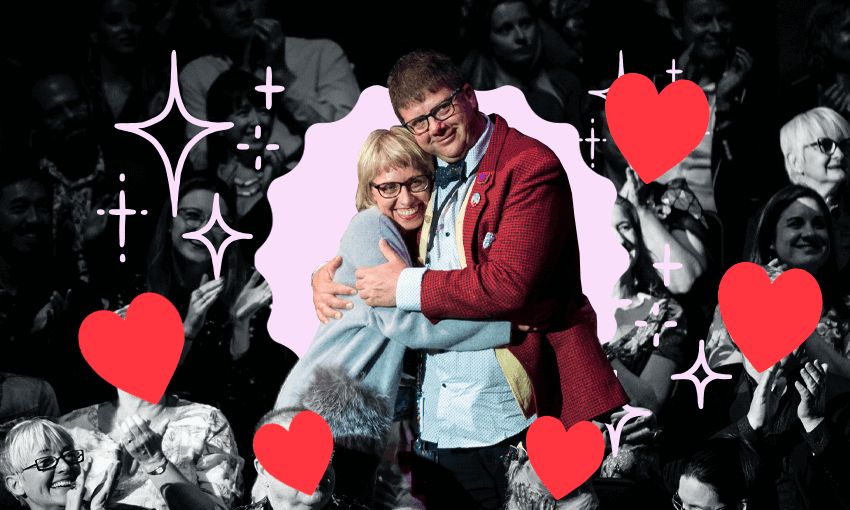

They’ve needed everything from horse floats and boats to get their creations to Wellington over the years, but Karl says that participating in WoW has never caused much stress in their relationship. In fact, he reckons WoW has been great for their marriage. “You’ve got the ups and the downs, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful.” The couple tend to disappear from social life in the months leading up to WoW, so much so that their friends and family refer to it as their “counselling” time.

“We only have cats, no kiddies, which makes it easier because there’s a lot of stuff always lying around – screws and nails and hot glue guns. But it’s good fun. We’re a good team.”

This year they will be heading back down to Wellington where their latest creation – ‘Unravelling’ – will feature in this year’s World of Wearable Art competition. Given that last year’s event was cancelled due to the pandemic, the pair haven’t seen the garment since they sent it off in June 2021. “I can’t even remember what my entry looks like so it’s gonna be really exciting to see,” says Erna. They will also be looking forward to seeing some of their fellow WoW-heads, a group called “the old trouts” who have been entering since the early noughties.

And once they’re back home in Karaka, it will be back to “counselling” they go. “There is one piece that I’ve been working on in my head for about six years now,” reveals Erna. “And I think it’s actually going to happen next year, but we are still figuring that out.” Karl’s been working on the prototypes with matchsticks, but he’s still figuring out elements of the mechanics. “The stuff she wants to do is too difficult for NASA scientists,” he laughs. “But we’re not competing against anybody else, we’re only competing against our own creative boundaries.”

The World of Wearable Art is on in Wellington from Sep 30 – Oct 16