Raging against your fossil fuel machines and swapping them for more efficient, better-performing electric options is one of the best ways to have a real impact, writes Mike Casey.

It’s pretty rare to be confronted with information that completely upends a strongly held belief, but a few years ago I had an emissions epiphany and it’s no exaggeration to say that it changed my life. Now I’m on a mission to show as many New Zealanders as possible that the best way to cut their emissions is by exchanging fossil fuel machines and cars for electric equivalents and running them off renewable energy from a combination of the grid, rooftop solar and batteries.

I can trace my electrification journey back to 2007 when I co-founded a business called GradConnection in Australia. It was sold to Seek in 2019 and my wife and I wanted to put some of our proceeds to good use and do something about climate change back home in New Zealand. We ended up buying some land near Cromwell and decided to plant a cherry orchard.

We thought planting lots of cherry trees was a pretty good option as far as climate action went. Luckily, we hired climate scientist Carly Green to prove just how worthy we were and her calculations showed that planting 9,300 of them would remove about three tonnes of Co2 emissions per year. Not too bad, but there was another much bigger number she gave us that caught our attention: if we ran the orchard in the traditional manner and bought diesel tractors, motorbikes, sprayers and frost-fighting fans, we would be pumping out around 50 tonnes of carbon emissions each year, or about 18 times the carbon we’d be sucking up via our trees.

Seeing that comparison laid out in front of me was a watershed moment. I realised that our intentions were good, but we were not focusing on the right thing. The obvious solution to reducing our emissions was to find a way to stop burning all that diesel in the first place. Over the past few years, that’s exactly what we’ve done. We planted the trees, obviously, but we also run the orchard with 21 different electric machines and we fuel them with electricity from solar, batteries and New Zealand’s renewable grid.

By shifting our focus from trees that capture carbon to using machines that just don’t emit it, we have reduced our on-farm emissions by around 95% compared to the status quo – and, as a very compelling bonus, we also save tens of thousands of dollars on diesel each year, and are confident we will have a negative energy bill soon because we’re selling electricity back into the grid at times of high demand.

While these electric farm machines were more expensive upfront, they are cheaper over the long run, they often perform better than their fossil fuel equivalents and they don’t pump out tonnes of waste that we basically bury in the sky.

So how does my rural story relate to homes and businesses? I believe many New Zealanders are also focusing on the wrong thing and could do with an emissions epiphany of their own.

Studies have shown that many still believe recycling is one of the best ways to address climate change (sadly, that was also an answer given by both Christopher Luxon and Chris Hipkins during last year’s election debate). Others who are more clued up on the science might avoid unnecessary flights, eat less meat or dairy, or choose to travel by foot, bike or public transport.

We need a tapestry of solutions to deal with our environmental issues, but if your goal is to reduce carbon emissions and you still have fossil fuel appliances or cars (and especially if you are considering getting new ones), it is a bit like trying to lose weight and going from eating 11 burgers a day to eating 10 burgers a day.

“Dinner table decisions” about how to heat the water, keep the house warm, cook the food and get around are likely to have the biggest impact on your individual emissions tally. I do a lot of public speaking and when I explain this, it’s clear that not a lot of people are aware of that.

Here are a few comparisons that show how important these decisions are from an emissions perspective. We’ll use domestic flights, since they are well known as one of the most emissions-intensive activities that an individual can do.

- If you buy a new petrol car instead of an electric vehicle, that is the emissions equivalent of 107 return flights between Auckland and Queenstown over the lifetime of that vehicle.

- If you decide to install a gas hot water heating system rather than a much more efficient hot water heat pump, that is the emissions equivalent of 20 return flights between Auckland and Queenstown over the lifetime of that system.

- Using LPG to heat your home rather than a heat pump is the emissions equivalent of 35 return flights between Auckland and Queenstown over the lifetime of that heating system.

- And while gas cooktops don’t use a huge amount of energy in the home, the fuel you need to burn is the emissions equivalent of six return flights between Auckland and Queenstown over the lifetime of the cooktop – and it also creates indoor air pollution that has been compared to secondhand smoke.

On our farm, the carbon emissions we will avoid over the next 10 years as a result of using electric machines is the equivalent of 1,413 return trips between Auckland and Queenstown.

While we pat ourselves on the back for our highly renewable grid, renewable energy makes up only around 30% of New Zealand’s total energy consumption. More than 70% comes from fossil fuels that feed our machines, and the more you think about this system, the crazier it seems: oil is dug out of the ground in the Middle East, sent to and refined in Singapore, put on big boats to New Zealand, driven around by big trucks when it gets here, and put in a tank at a station that you have to then travel to. To add insult to injury, only around a quarter of the fuel is used to move the wheels (the rest is wasted as heat, noise and vibration), the price of these fuels keeps going up, and it negatively affects our air quality and health outcomes.

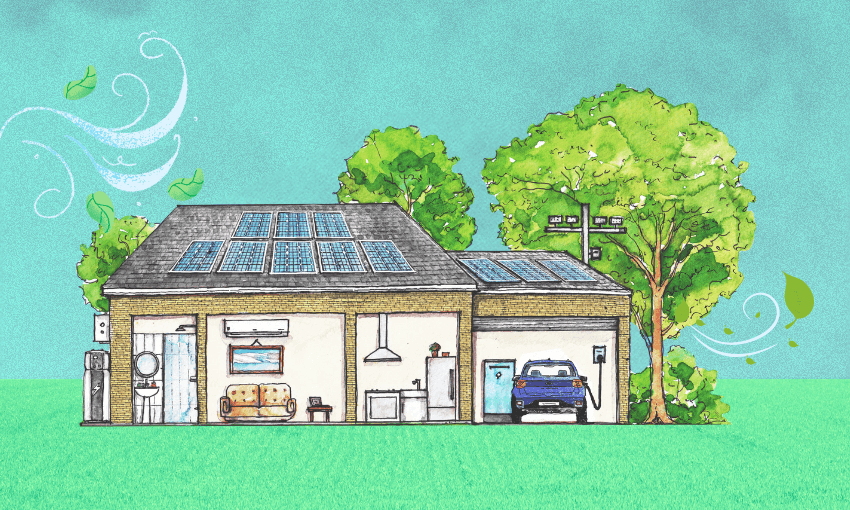

Or, we could opt for a more sane model: use electric machines and charge them with mostly renewable energy generated in New Zealand or completely renewable energy generated with rooftop solar (the cheapest form of energy available to New Zealand households today and the cheapest form of energy ever developed by humans). There are also a few cherries on top: the cost of all these things is dropping, they are much cheaper over their lifetime than fossil fuel equivalents even with finance included, and our air remains unsullied.

The traditional approach to decarbonisation has been to concentrate on high-emitting sectors like aviation, agriculture or manufacturing. But when you look at where our domestic emissions come from, small fossil fuel machines in households account for around 30% of the total, and the technology exists to replace them today. That number is much higher when you factor in all the machines in businesses and on farms.

Green steel and electric planes will take years to scale up, so while we wait for solutions to the big, difficult stuff, we should instead be focusing on the significant reductions that are immediately available with the small, achievable stuff. Farmers and homeowners can save money and reduce emissions if they focus on their major, fuel-sucking appliances first (cars, water heaters, space heaters, cooktops). We would argue the government also needs to shift its focus and look at the emissions reductions that could be achieved from supporting the electrification of our homes, something Rewiring Aotearoa outlined in its submission to the second emissions reduction plan.

Climate change is a cumulative emissions problem, which means we will have more impact if we reduce emissions quickly. We should be helping more people swap their machines right now, rather than waiting until 2030 and then potentially having to buy expensive offsets (ie trees, which may or may not materialise) from other countries that have done a better job than us.

We’re not suggesting that anyone who buys an EV or a hot water heat pump gets a free emissions pass to fly every weekend. We are trying to show there are very effective ways to reduce a huge chunk of your emissions that often fly under the radar. There is a real lack of awareness about how much of an impact you can make by raging against your fossil fuel machines and swapping them for more efficient, better-performing electric options – and that’s what we’re trying to address.

The sacrifice narrative has long been a part of the climate movement. We focus on the substitution narrative: electric machines that allow people to keep doing the things they love with less of an impact and at lower cost. Electrification should be our first stop when thinking about how to be more energy efficient, before stressing about things like shorter showers or turning off the lights, because while we will inevitably use more electricity as we transition to renewables, we will use much less energy and far fewer materials overall – and those are the bits that hurt our environment.

It’s clear that many of us have good intentions when it comes to the climate, but there’s often a large gap between what we say and what we do. As the aptly titled book Everybody Lies suggests, everybody lies – to themselves, to their friends, and to people conducting surveys to gauge environmental sentiment. Good decisions are better than good intentions and that requires good information – and helpful comparisons.

When it comes to reducing our emissions, we need to be able to see the forest for the trees. By all means, do some planting, reduce your flying, bike to work and cut back on the steaks, but if you really want to have an impact and you get to choose the machines in your life, focus on the fuels first.