A new art space for Māori, Pasifika and marginalised communities in central Auckland aims to be more than just an art initiative, as Arizona Leger explains.

There’s something powerful about experiencing revolution in its early stages. And that’s exactly what’s brewing on a street in the 312.

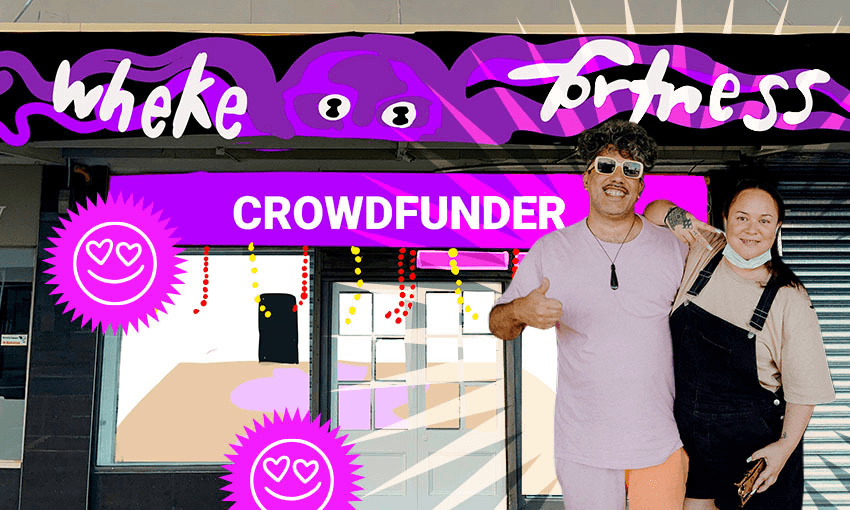

Dressed in the best shades of pinks and pastels, Tokerau Brown (he/they) waits near the block of shops on Trafalgar Street, Onehunga. We greet each other with a Covid-inspired, hugless hello and make our way into Wheke Fortress, a new community arts studio and gallery .

As we enter a predominantly empty room there’s a shared excitement about two boxes packed with flash new chairs and, on my right, a whiteboard decorated with a large wheke (octopus) swimming amongst several scribbles.

We sit down, but before I can get a word in Brown, known to most as Toki, leaves for the dairy to grab a water and bhuja mix for our kōrero.

For a moment, I sit alone in the empty space, surrounded by blank walls, and wonder if this is what it looks like to realise your dreams. Having run a record label and animation studio out of their own whare, Brown and partner Jessicoco Hansell (she/they, also known as Coco Solid) plan for Wheke Fortress to be an environment where emerging creatives feel safe to experiment with their craft and create revolutionary concepts.

Brown returns and we make time for whanaungatanga, or “connection”. The topic of our interview was to learn about Wheke Fortress’s Boosted crowdfunding campaign, which was well on its way to meeting its $50,000 target, but taking time to connect via our ancestors opened the door for an entirely different conversation.

Brown begins to explain his whakapapa. Mum from Otago, dad from several islands in the Cook Islands. He says that “connecting back” is a key part of his story right now.

Hansell, dressed in overalls and with tattoos protecting her arms, pops in to check on how things are going. I answer the only way I know how – “he uri ahau nõ Te Rarawa me Whakatõhea” – and Hansell raises her eyebrows, an unspoken signal that everything’s tūturu, that we are good to proceed.

“It’s early days and humble beginnings, but the support that people have shown towards our Boosted account indicates the demand for an ‘actual community space’ instead of ‘imposter community spaces’” Hansell says of the crowdfunding drive that brought Wheke Fortress to life.

She talks about no longer being guests in art spaces, especially when being in Aotearoa means that these spaces are whenua and birthright. The themes of reclamation and restoration are woven heavily through both their answers to my questions

Hansell has a look in her eye that says she means business. She tells me straight up that if I were a “Palagi journalist” I would’ve been given a “wooden, polite, formal soundbite version of the origin story”.

“But because you’re tūturu and Pasifika… we’re able to tell you a real story, because we trust that you go and you represent us safely.” I can hear my mum saying “I told you so” after all the times she’s reminded me to start conversations with my pepeha and I’ve been too shy to follow through. This is no longer going to be a simple story about a Boosted campaign.

Now that the fala has been rolled out, I’m eager to learn about the origin of Wheke Fortress. “It’s cos we’re punks,” says Hansell. “Artistically, I think you should be wired for rebellion.”

That assertive look in her eye is back. “You should be looking for the most rare and radical entry point. We are wired for DIY, new models of industry, moving away from colonial white, patriarchal misogynist shit.”

She isn’t finished.

“And I don’t think it will be perfect. It shouldn’t be, you know? Because we’re giving ourselves the public permission to learn.”

Brown and Hansell take me on a waka through time, sharing the ways in which they have always loved art and how art spaces pick and choose when to love them back.

What’s undeniable is their determination to ensure that Wheke Fortress carries an intergenerational kaupapa. One where everybody informs each other’s lens, including their way of thinking and way of moving. They’re also clear that Wheke Fortress aims to serve a moment in time rather than last the ages, that they’ll know the kaupapa is working when they see other artists empowered to make similar spaces of their own.

Although both Hansell and Brown have had success as artists, they say the inspiration for Wheke Fortress came from their experience of the Aotearoa arts community failing to create genuine spaces for marginalised artists to explore and exist.

Brown mentions that he’s reluctant to create pain-filled “trauma art”. Instead of focusing on his culture’s pain, he wants to dream about a future for his people. He’s expanded this dream to include enabling a space where Oceanic narratives, wāhine, LGBTQIA expression and underground creatives of colour can feel safe. A place where they can experience something he never could at a younger age. That space is Wheke Fortress.

Beyond that space of safety, what will come to life within these walls?

Wheke Fortress will mentor experimental musicians through to the various stages of their craft, provide unique residencies and offer studio space to creatives. Put simply, it’s “a space that everyone can share,” Brown explains before pointing me in the direction of several kaupapa that he admires. On that list, Vunilagi Vou, Moana Fresh, Tautai – all highly-respected community arts spaces.

He hopes that Wheke Fortress will be less harmonious and more representative. “It’s about getting to be your true self within a space where you are supported.”

Brown talks about a moment when he and two other creatives were vibing off each other because of familiarity, and because they felt safe enough to speak openly and give things a go. Afterwards, he knew that Wheke Fortress was the right kaupapa to believe in because “you got three people feeling safe in their element and all these ideas just pop off. That just never happens for me in other spaces where I don’t feel that support.”

He says the creativity that occurs within a safe space is different. “It’s much stronger. It becomes more revolutionary.”

By this point, our dairy-bought water bottles are at room temperature and the bhuja mix still unopened. The spark that both Hansell and Brown share for the purpose of Wheke Fortress is undeniable. It’s easy to imagine the lives that will flow in and out of these doors once the Fortress launches.

Before we say goodbye, Hansell reminds me that Wheke Fortress is more than an arts initiative. It’s a message to and about gentrification. As a Māngere Bridge, Grey Lynn girl, she’s familiar with the pattern and refuses to be a passive participant in another gentrifying area.

Wheke Fortress is Hansell’s way of ensuring that Māori, Pasifika and marginalised communities continue to pack the streets of Onehunga.

Our conversation has eliminated the construct of time. What once felt like an empty room has filled itself with stories and hopes for the future. As Brown and Hansell go forth with what they have planned, this “fortress” will see many artists discover, activate and relish in their talents. It’ll become a firm reminder that it’s not just about houses, it’s about having a place to call home.

While writing this article, Wheke Fortress achieved its Boosted Campaign goal, which will see the team secure over $50,000 to bring this revolution to life. A true testament to the need for more environments where creatives feel safe enough to test, trial and sample their craft.

As I leave, Brown and Hansell ask me to give a shout out to the local food shops in Onehunga, namely Chic’en Eats and Saltwater Burger. Apparently the fish and chip shop across the road from Onehunga Countdown is hugely slept on.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.