Today is Ash Wednesday, when the annual 40 Days for Life anti-abortion campaign kicks off. This year, explains ALRANZ president Terry Bellamak, the pro-choice counter-protest has a new focus: breaking the silence.

A large majority of New Zealanders trust women and pregnant people to decide for themselves whether to receive abortion care. Only the people involved understand what is best for themselves and their families. Everyone deserves the freedom to decide whether and when to become a parent.

Every year, 40 days before Easter, anti-abortion groups launch a campaign called 40 Days for Life. Every year, ALRANZ responds by sharing actual facts about abortion under the hashtag #40daysfortruth, and by setting up a Givealittle page to thank abortion providers with treats.

This year, we want to address something bigger.

Abortion care is health care that one in four Kiwis who can become pregnant will decide to receive over the course of their lives. Many people don’t talk about their abortions – not necessarily because they feel ashamed, but because they don’t feel safe.

That is abortion stigma at work.

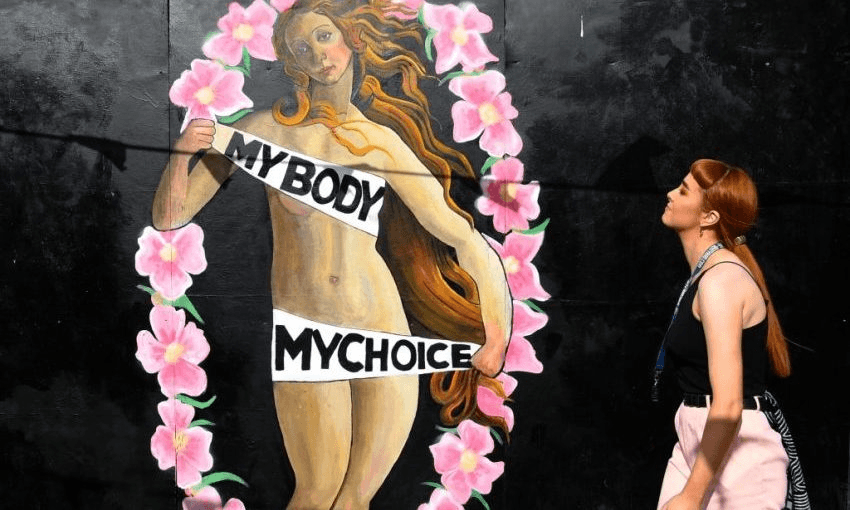

Abortion stigma is negative qualities projected onto women who receive abortion care. It serves as a justification for treating them badly. Fear of humiliation and violence keeps people silent.

When anti-abortion protesters target pregnant people entering abortion clinics with shouts of ‘whore’ and ‘murderer’ and throw plastic foetuses at them, that is abortion stigma.

When police refuse to intervene in the harassment because abortion is ‘different’ to other kinds of health care where people are not allowed to be harassed, that is abortion stigma.

When ‘counsellors’ think it’s OK to lure pregnant people into their offices with the promise of unbiased counselling, only to turn on the anti-abortion hard sell once the door is closed, that is abortion stigma.

Receiving abortion care is nothing to be ashamed of – it’s health care, and people are not doing anything wrong. What’s actually wrong is deceiving people, harassing people, calling them names, and trying to intimidate them. Those are the things people should be ashamed of.

ALRANZ Abortion Rights Aotearoa wants to end abortion stigma, and the distress and isolation it creates. We believe the best way to do that is to share our stories.

ALRANZ would like to invite anyone who has received abortion care to tell one person about your experience. It doesn’t matter who. The first time you tell your story is the hardest. But very often, you meet with understanding, acceptance, and perhaps a story similar to yours.

ALRANZ would also like to invite you to tell us your story. We will post it anonymously on our new Facebook page, Abort The Stigma. The page works pretty much exactly like the In Her Shoes – Women of the Eighth page in Ireland. You might call it an homage.

Everyone has the right to decide whether they are ready to become parents. When you think about it, it’s quite weird that some people think they should be able to force their own beliefs on others who don’t share them, or that they know better than you do what’s right for your life or body.

Abortion stigma needs to suffer the fate of all moral panics that are really nobody else’s business. Tell your story and help us abort the stigma.

Terry Bellamak is the president of ALRANZ, the Abortion Law Reform Association of New Zealand.