Summer reissue: With funding ending for Archives New Zealand’s digitisation programme, Hera Lindsay Bird shares a taste of what’s being lost – because history isn’t just about the big-ticket items.

The Spinoff needs to double the number of paying members we have to continue telling these kinds of stories. Please read our open letter and sign up to be a member today.

First published May 16, 2024.

On Tuesday morning the PSA held a snap protest outside the National Library in Wellington, urging the government to continue funding the ongoing Archives New Zealand Te Maeatanga digitisation programme, currently set to end in June this year.

The programme, which has been running since 2017, has digitised more than one million records, most of which are currently available online. But there are still four million records held by Archives yet to be digitised. Archives NZ preserves records, correspondence, photographs, and recordings of national significance from government and public institutions, dating from 1840 to the recent past. Types of files you might find in the archives are court and police records, coroner’s inquests, artworks, school archives, land registration documents and politicians’ papers, among many others.

In a speech delivered at the protest, Eoin Lynch, a PSA delegate for Archives NZ, said, “People need to be able to access these records. They help people navigate complex legal processes. They also help people research their whakapapa and genealogy using the shipping records and records from the Māori Land Court. Accessible public records are a fundamental part of our democratic society. Public records help keep our government transparent. Freely accessing records enables us to claim our rights and stay connected to our heritage.”

There are plenty of reasons to pursue digitisation. It speeds up our bureaucratic processes, protects our records from accidental obliteration, encourages the writing of prize-winning historical fiction and helps New Zealanders apply for pensions, citizenship and research their family history.

Currently, undigitised records can be accessed in four Archives New Zealand reading rooms across the country, in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin. If you’re looking for a record unavailable in your region, you must travel to the record’s location to access it, which is both expensive and time-consuming. And in 2020, the Archives reading rooms slashed their opening hours in order to focus on their digitisation project.

It’s not hard to make an argument for everyone having easy online access to Te Tiriti, the suffrage petition, or even Hone Heke’s wanted poster. But history isn’t just about the big-ticket items. One of the best things about the Archives is the wealth of information it wouldn’t occur to you to look for, such as the full-page advertisement of a young Rachel Hunter in a swimsuit, under the legend “Trim Milk Give It To Your Body”. Or some shonky photos of Darth Vader visiting a Hamilton primary school.

To celebrate some of our fleeting moments of national insignificance, here are 10 of my favourite finds from the Archives NZ Flickr account.

1. Doesn’t matter

Not only did Penrose High School boast some of the most eye-watering carpets ever seen outside of a condemned Illinois video game arcade, but this page of overwrought anti-nuclear student poetry from 1984 is nothing short of perfection.

“It doesn’t matter now/That I never read/Shakespeare’s sonnets/ or Pam Ayres poetry./ Nothing matters now./ For we will die tomorrow.”

Adrian Mole eat your heart out.

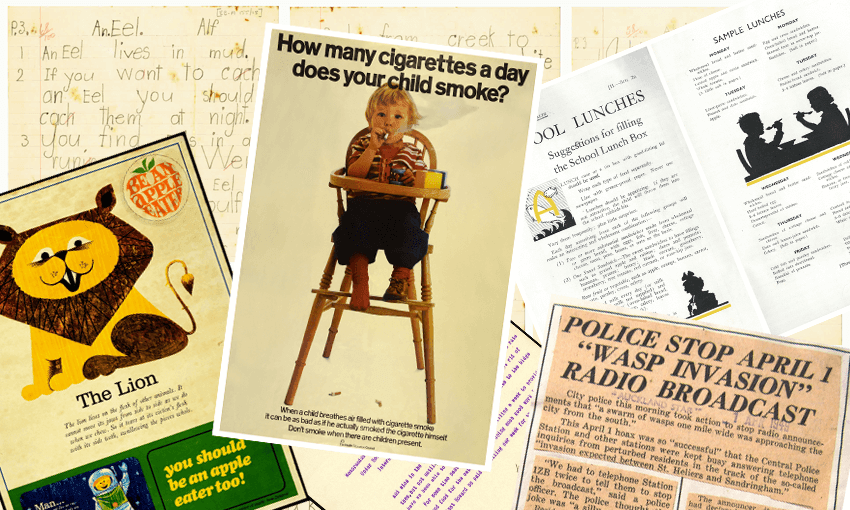

2. How many cigarettes a day does your child smoke?

No national archive would be complete without a robust cross-section of healthy eating propaganda and anti-spitting campaigns, but you have to love a good anti-smoking ad. How do they always get it so wrong? Every anti-smoking poster is, at its heart, a secret advertisement for smoking. Has a baby ever looked cooler?

This atmospheric cigarette poster would also look great on the back of a silk bomber jacket.

3. Unwoke school lunches

There are lots of reasons not to be nostalgic about the past. War. Poverty. Racism. Homophobia. But life-threatening illnesses and identity-based discrimination aside, the thought of eating a grated apple and raisin sandwich, followed by a raw turnip every day fills me with dread. I’m sorry, but that’s sicko behaviour. I wouldn’t last a day in an early 20th-century New Zealand primary school, and this suggested menu from the NZ Health Department proves it.

4. A 14-inch koala

The early 20th century was a wild time. Not only were the vast majority of drugs completely unregulated, but records suggest that adopting wild foreign animals as pets was as simple as writing a polite letter to the DIA. There are so many records relating to the importation of live animals they almost deserve their own ranking, but some of the records include:

1886: A request to release hundreds of ferrets onto a Southland farm (permission granted, contingent on the farmer sourcing “high-class” ferrets.)

1911: A request to import two wallabies as pets for Napier Boys High School (permission granted.)

1911: A request to import six snakes for T Bradley of Masterton (permission denied.)

1911: A request to import six snakes for J C Williamson (permission granted, provided the snakes were non-venomous, and returned to New South Wales within eight8 weeks.)

1912: A request to import a very small (14 inches long) pet koala (permission granted.)

And my personal favourite:

1912: A request to import red squirrels and two raccoons as pets (squirrels: permission granted. Raccoons: permission denied.) The archivist notes that “The department gave no reason for their decision to decline the importation of the two racoons Reid also wanted to keep as pets, but a clue may be found in the scribbled note on an Internal Affairs file: “Racoon is a carnivorous mammal allied to the Bear about the size of a dog”.

5. Did… did a lion write this?

This has to be the weirdest campaign ever sponsored by the NZ Apple and Pear Marketing Board.

“The lion lives on the flesh of other animals. It cannot move its jaws from side to side as we do when we chew. So it tears at its victim’s flesh with its side teeth, swallowing the pieces whole.”

6. For some years we have been much troubled with rats

I think this might be the cutest letter in the national archives. In 1912 Captain WH Hennah wrote to the undersecretary of internal affairs, requesting a shilling per week for Howard, the nightwatchman of the government buildings, to provide milk and food for the cats “who are doing such good work”. Readers will be happy to hear Howard’s request was granted, and the cats were rewarded for their valuable national service.

7. A swarm of wasps, one mile wide

These days, April Fool’s Day is a tedious, corporate affair, where multinational corporations compete to author the most insipid prank calculated to avoid national panic. Not so in 1949.

This article details a prank gone wrong, when 1ZB radio announced a “swarm of wasps one mile wide” was heading for the area between St Heliers and Sandringham. Residents were encouraged to “smear honey and jam on paper and place it outside windows”, and secure the bottom of their trousers. The announcers advised listeners if they had any questions or concerns, they should call the Department of Agriculture or the police for advice. Gottem.

8. You god damned bugger of hell

There’s something irresistibly charming about this frontier record, which dates from 1879 in the Otago and Southland gold rush, and concerns the behaviour of one William Maclarn, written up for using foul language on a public road at 4.30pm in the hearing of children. The foul language in question?

“Morton you bloody low thief you son of a whores bitch you god damned bugger of hell I will do for you yet.”

Quick, someone call Walton Goggins’ casting agent. I looked through the rest of the archives for any mention of William Maclarn and found references to many other undigitised records which seem to suggest a pattern of troublesome behaviour. I also found this 1896 Frances Hodgkins portrait of William Maclarn. I can’t definitively prove it’s the same William, but considering the dates and geographical proximity, I think there’s a good chance this is the face of a notorious foulmouth.

2. All our rabbits are dead

Who doesn’t love a droll letter from a child? Especially one addressed to Santa, in the shape of a bell, that ends with “all our rabbits are dead”.

A close second in this category is this lovely story of an eel, written in 1935 by Alfred Williams of Moheau School in Coromandel, in which he describes the eel as a “loing thing, adding “Wen you cach an Eel it wines its soulf a bout.”

1. Girls leading life of open immorality

Honourable mentions and interesting pictures:

Clubbing in Johnsonville, rugby trash, the first McDonald’s, “con-artist” Amy Bock, aerial view of a Rail Service Meal, capitalist vampires, James Joyce degenerate and Robert Muldoon atop a throne of sheep.