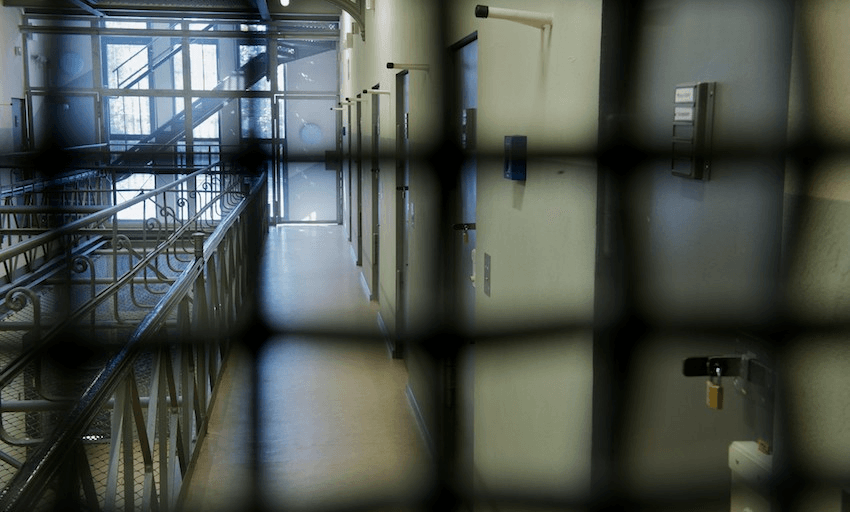

The government is about to make a final decision on a 1500-bed expansion to Waikeria Prison that would make it larger than even the biggest prison in the UK. Anti-expansion campaigner Roger Brooking explains why building more and larger prisons is exactly the wrong solution to our incarceration epidemic.

Cutting the prison population by 30% – quick fix solutions

In September 2017, New Zealand’s prison population hit an all-time high of 10,470, of whom 2,983 or 28% were on remand. I give the background to and reasons for this boom in my column Explaining NZ’s record high prison population.

Whatever the causes, the situation is clearly out of control. The operating cost of our prison system is about $100,000 per prisoner or $1.5 billion a year. Before it left office, the National government put in motion plans for a new prison at Waikeria at an estimated cost of $2.5 billion. According to new justice minister Andrew Little, unless we start doing things differently, New Zealand will need to build a new prison every two or three years.

At the 2017 election, Gareth Morgan proposed reducing the prison muster by 40% over ten years. The Labour coalition wants to reduce it by 30% over 15 years. However, Andrew Little and Corrections Minister Kelvin Davis have been very vague about how they intend to achieve this while making no obvious effort to cancel the Waikeria plans.

Reducing the prison population is not difficult. The simplest approach is to repeal most of the ‘tough on crime’ legislation that has been passed in the last 25 years. There are also some easy administrative fixes which will reduce the prison population by up to 3,000 very quickly.

1. Reduce the number of prisoners on remand

Of all the punitive legislation passed since 1980, the Bail Amendment Act in 2013 produced the biggest bump in prison numbers. This disastrous piece of legislation was introduced after the murder of Christie Marceau by 18-year-old Akshay Chand while on bail. However, this was not a failure of the existing bail laws. It was the result of an inadequate risk assessment by the mental health services dealing with Chand, who was subsequently diagnosed with schizophrenia and found unfit to stand trial. He was released after a forensic health nurse advised Judge McNaughton that Chand had been taking anti-depressant medication for two weeks and could be “safely and successfully” treated in the community.

In response to the media outrage at the murder, led by Garth McVicar of the Sensible Sentencing Trust, the National government passed the Bail Amendment Act, making it much tougher for defendants to be granted bail. Projections by the Ministry of Justice claimed the new Bill would increase the number of prisoners on remand by less than 60. But three years later, there are 1,500 new prisoners on remand. None of them have yet been convicted of a crime. They’re being held in prison because a mental health nurse, not a judge, got it wrong and because National gave in to whipped-up moral hysteria. As a result, the Corrections Department says we need a new prison. We don’t. We just need to repeal the Bail Amendment Act.

2. Release more short-term, low risk prisoners

The other quick fix is to let out more short-term prisoners early. The Parole Act defines a short-term prison sentence as one of two years or less. Short-term prisoners don’t go before the parole board – they’re automatically released after serving half their sentence. In 2015, there were nearly 1,900 short-term inmates on a given day (although thousands more than this cycle through the prison within a 12 month period). The Board would be totally overwhelmed if it had to see all these inmates, many of whom are in prison for quite minor offences. So automatic release at the half-way mark is an administrative convenience.

A long-term sentence is anything over two years (from two years up to life). Since 1985 ‘tough on crime’ legislation has significantly increased the number of long term prisoners (see chart above); the number of people given ‘long term’ sentences between two and three years went up 475%. In 2015, there were 765 inmates in this group, out of a total of nearly 5,000 long term prisoners.

These prisoners can only be released before the end of their sentence if the Parole Board decides they no longer pose an ‘undue risk’ to the community. Most attend their first parole hearing after completing one third of their sentence. But that doesn’t mean they get out. In the last few years, the Parole Board has become increasingly risk averse and now less than 5% of inmates are released at their first hearing – after which they serve the rest of their sentence in the community under the supervision of a probation officer. Most long-term prisoners now serve approximately 75% of their sentence. The remainder serve their entire sentence.

So if the definition of ‘short-term’ was changed from two years to three years. That would allow an additional 765 inmates to be released automatically after serving half their sentence. Prisoners serving four or five years could be automatically released after serving two thirds. In 2015, there were 1,645 inmates serving between two and five years. Add this to the 1,500 no longer being held on remand and within five years, the population would be down about 3,000 – which is 30% within five years.

Prisoners also need accommodation and jobs when they get out. That requires long-term solutions, which would reduce the prison population by a further 20%.

Cutting the prison population by 50% – long term solutions

Cutting the prison population by 30% is easy: repeal the Bail Amendment Act and allow more short-term prisoners to be released after serving half their sentence. But to get to 50%, we also need to stop putting so many people in prison in the first place. And we need to reduce the re-offending rate. Unlike the quick fixes, these will require some financial investment.

1. Increase the price of alcohol and decriminalise cannabis

Despite the endless scaremongering about methamphetamine and synthetic cannabinoids, alcohol is by far the biggest drug problem in the country. In Alcohol in our Lives, the Law Commission said 80% of all offending is alcohol and drug related. The Commission concluded that increasing the price of alcohol 10% (by raising the taxation component) was the single most effective intervention to reduce alcohol-related harm and would raise $350 million in revenue. It also recommended an increase in the legal age of purchase to 20, restricting the sale of alcohol in supermarkets (which now account for 70% of all alcohol sold in New Zealand), and an increase in funding for addiction and mental health treatment. The National government ignored all these recommendations.

Decriminalising cannabis would also help keep drug users out of prison. If the government wanted to be really bold, it could decriminalise possession of all drugs, as Portugal has done. This strategy is supported by the New Zealand Drug Foundation, which recently released Whakawatea Te Huarahi, “a model for drug law reform which aims to replace conviction with treatment and prohibition with regulation… under this model, all drugs would be decriminalised. Cannabis would be strictly regulated and government spending on education and treatment increased.”

This would make a big difference. In 2015, offenders with drug offences accounted for 13% of all sentenced prisoners. So apart from a few big-time drug dealers who would remain in prison, if personal possession was decriminalised, that’s another 800 people or so that could be treated in the community instead of in prison.

2. Increase the number of drug courts

Decriminalisation needs to be aligned with a significant increase in funding for drug courts. Here’s how they work: when someone appears in court with alcohol or drug related offending, the judge gives him a choice. Instead of sending him to prison for the umpteenth time, if the offender agrees to be dealt with in the drug court and go to treatment, he may avoid going to prison.

The offender comes back to court every two weeks so the judge can monitor his progress. The whole process usually takes about 18 months. If the offender successfully completes everything he’s told to do, he avoids a prison sentence. Those who ‘graduate’ say this process is much tougher than going to prison.

This is a highly effective intervention. But right now, there are only two drug courts in the whole country, and they ‘treat’ only 100 offenders a year. Over the next five years, New Zealand needs to increase the number of drug courts to at least ten. This will require a significant increase in funding for alcohol and other drug treatment services in the community, but it would keep at least 500 offenders a year out of prison. If drug courts were rolled out nationwide, even more could be managed in the community.

3. Increase funding for reintegration services

Sending fewer people to prison is paramount. Reducing the risk of reoffending is equally important. Currently, within 12 months, 28% of ex-prisoners are back inside. After two years, 41% are back in prison. These figures have changed little in the last 20 years, despite a massive increase in the availability of alcohol and drug treatment in prison; and despite a concerted effort by Corrections in the last few years to reduce reoffending by 25%.

The problem is Corrections spends approximately $150 million a year on rehabilitation programmes in prison – on programmes that don’t work. There’s a reason they don’t work. The reality is that 15,000 people (most on short sentences) are released from prison every year. Many are alienated from family and have nowhere to live. Very few have jobs to go to. Hundreds have no ID, no bank account and struggle to register for the dole. In Beyond the Prison Gate, the Salvation Army recommended that “That the Department of Corrections ensures all ex-prisoners are provided with six months of accommodation… and create industry schemes that will employ prisoners for … 12 months post release if they have no other employment.”

Here’s the crux of the problem. While the Department spends $150 million on rehabilitation in prison every year, in 2017 only $3 million was budgeted for supported accommodation – for an estimated 640 ex-prisoners. Until $150 million is also spent on half-way houses and reintegration services, the funding spent on rehabilitation in prison is money down the toilet.

There are many other options available. But until we have a government with the courage to ignore the moral panic perpetuated by the Sensible Sentencing Trust over the last 20 years, our prison muster will continue to proliferate. And billions of taxpayer funds will be wasted on the dubious delusion that locking citizens away creates a safer society.

Roger Brooking is a Wellington based alcohol and substance abuse counsellor. Read about his campaign to cut the prison population by 50% and sign the petition against the planned mega prison at Waikeria at cuttheprisonpop.nz.

This section is made possible by Simplicity, the online nonprofit KiwiSaver plan that only charges members what it costs, nothing more. Simplicity is New Zealand’s fastest growing KiwiSaver scheme, saving its 12,000 plus investors more than $3.8 million annually in fees. Simplicity donates 15% of management revenue to charity and has no investments in tobacco, nuclear weapons or landmines. It takes two minutes to join.