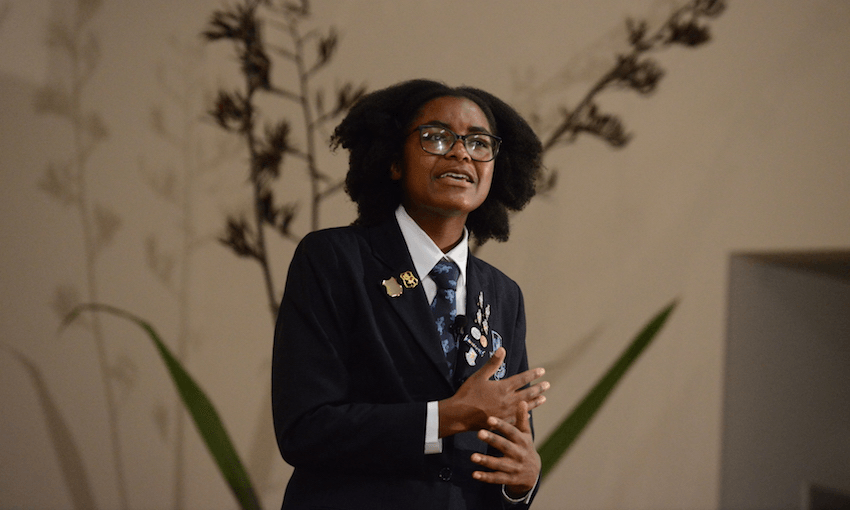

The annual national Race Unity Speech awards happened in Auckland on Saturday, where six of New Zealand’s best high school speakers addressed how we can improve race relations. Year 13 Mount Albert Grammar School student Takunda Muzondiwa spoke about struggling to stay connected to her home in Zimbabwe, while trying to create a new home in Aotearoa.

At the age of 7, my family immigrates from Zimbabwe to Aotearoa. I pass through Customs but my culture is made to stay behind. In the classroom, I am afraid my tongue will beat back to its African rhythm, be concussed by fear, have amnesia turn all its memories to dust.

Yesterday I was African, today I am lost. Maybe I was blinded by the neon sign of opportunity, failed to read the fine print that read: “assimilate or go back where you came from”.

I have been led astray, like Eve to the snake, like promises of wealth to the prodigal son. I am a child of the diaspora, a common thread amongst my people in the fabric of what displaces us from our homes. Sometimes it’s by choice, most often it is not. To be a child of the diaspora is to battle two tongues and be forced to trade one for another so much so that my articulation of the English language now tastes like the un-birthing of my country.

When I return to Zimbabwe to connect with my roots I feel I am a jigsaw piece in the wrong puzzle. Zvinochikisa kuva mhunu asinga ziva nyika yangairi yake pekutanga. It’s an emptying feeling, to become foreign to a country that was yours to begin with. I am beginning to forget the taste of my own language and home has become just a memory.

Home is a concept that feels somewhat elusive to me because while I’m a resident in Aotearoa, coming from an immigrant family, I’m in a position that pushes outside of my social and cultural comfort zone. Like most immigrant families my parents migrated in search of quality education and success for their children.

When I reflect about how race has affected me personally I realise that at some point I came to believe that the only way I was going to reach those aspirations that my parents desired for me was to assimilate to the culture and assume the values and behaviours of New Zealand, thus neglecting the qualities which were inherent to me as Zimbabwean.

Unfortunately, these same kinds of beliefs are common amongst ethnic minorities. I believe the power to re-empower those marginalised communities is in the hands of our educational institutions.

In Aotearoa, Māori students are falling behind on every measure of educational outcome including secondary school retention rate, school leavers achieving NCEA Level 2, and the rate of youth in education or employment. However, those who attend Maori immersion schools perform much better and achieve much higher in NCEA, university and employment. It’s clear that systemic bias and the enduring legacy of colonisation is behind this ongoing disadvantaging of Māori people.

It is an unfortunate recurring issue that students of minority groups tend to feel as though they don’t belong in an educational context because there are lower expectations of them. It’s time our educational institutions place a greater emphasis on language, culture and history. If educators were informed more on these topics they would come into the profession with a different perspective- one where they are less likely to hold racist or biased views.

It’s no secret that the more students feel they belong in an educational context the better they perform. I truly believe we can shift these educational inequalities if we cultivate culturally flexible minds and empower all students with the knowledge that they have both the responsibility and right to be there.

A powerful novel called Decolonising the Mind speaks of the writer’s time in colonial Kenya. He describes how at the time violence was the means of physical subjugation whilst language was the means of spiritual subjugation. Those who were caught speaking their mother tongues in the classroom they would either be physically tortured or publicly humiliated, and that was a critical aspect of the suppression process right? That the language of those being oppressed was dissociated from them. The scary thing is that these same patterns are repeating themselves today among our Māori community as they hold the fear of “what will become of their home when it loses its language completely?”

Poet Pages Matam describes language as being both a tool for communication and a vehicle for culture. I find that to be such a beautiful description. Language is saturated with history, culture and memories. Language and words are powerful tools to inform people of different ethnicities to better understand the world views and perspective of one another.

I believe unity comes from a better understanding of one another as people. The best way I know how to share the perspective of those I represent as a black immigrant woman is through my writing. I write my poetry and I send it to the man who sat behind me on the train last week who had the audacity to touch my hair without even asking.

“I guess the basic human concept of respecting personal space doesn’t apply to you?” I didn’t actually say that which is crazy because I almost always have something to say but in that moment like my split ends my mouth was too dry to speak.

But luckily my hair, my hair speaks volumes. Tangled and twisted there are stories in these in curls. Stories of a mother, father stamped with a number marked as objects sold for property. Stories of my ancestors shackled in cages displayed in zoos the same way you stroke me like an exhibit in a petting zoo.

It’s twisted and tangled there are stories in these curls. A beautiful possession of my history’s oppression.

You look at me like I am Medusa’s child. Cursed. Making everyone blind to my self-worth. For years I tried to strip myself of this curse with a potion of chemicals despite the burn of sodium hydroxide on my scalp the smell of burning flesh that filled the room I was hypnotised by the prospect of having straight hair cascade around this broken body of insecurity.

Hoping to put myself back together with glued in weave tracks causing receding hairlines as I also mentally recede back, back in time to a time of my ancestor’s inferiority a time of no authority forever believing that I was the target minority.

You can’t tell me to tame this mane because in fact, you are the lion. And in this jungle where racism runs wild, I am your prey you are my predator devouring my history leaving me so raw that my own flesh builds a grave for me to lie in. I’m buried deep in my roots. And I understand I may be dead but God, can you re-humanise the systematically dehumanised?

That poem speaks of my experiences with internalised racism which is a system in which minorities are unconsciously rewarded for behaving in such ways that uphold whiteness and white supremacy. In the words of Dr King, “Somebody told a lie one day… they made everything black, ugly and devil.”

These lies have people believing that lightening your skin and constantly chemically straightening your hair will draw you closer to success or the ideal standard of beauty.

It is time to replace the lie of racial inferiorities with the truth of a shared humanity. To change we need our media sources to provide a diverse representation of people, portraying people of colour as the standard bearers of beauty, professionalism and success along with their white counterparts.

So dear racism, I’m rewriting the history you gave me because I know the future belongs to those who prepare for it and you have been preparing me for centuries.

Takunda Muzondiwa migrated to New Zealand with her family when she was seven from Zimbabwe and is currently head girl at Mount Albert Grammar School.