Few cities have ever attempted to build a connected cycling network this quickly.

Windbag is The Spinoff’s Wellington issues column, written by Wellington editor Joel MacManus. It’s made possible thanks to the support of The Spinoff Members.

Wellington’s cycleway debate is an interminable bore. We’ve had the same mind-numbing arguments over and over again for years. Bike lanes are constantly being knocked back by legal cases, budget cuts, and comment section outrage. The pace of change feels incredibly slow when you’re in the middle of it.

Last week, I caught up with Skye Duncan, the executive director of the Global Designing Cities Initiative. Her team was in Wellington offering training and support to council staff as part of the Bloomberg Initiative for Cycling Infrastructure. Wellington was one of 10 cities worldwide that won a grant from the organisation last year.

Bloomberg and the Global Designing Cities Initiative are interested in Wellington’s cycleway programme because it is a rare case study of how quickly a city can build widespread cycling infrastructure. It was a refreshing perspective to note that Wellington is moving at light speed by global standards. Only a small number of cities have ever built a network this large this fast: Seville in Spain, Fortaleza in Brazil, Bogota in Colombia and… that’s about it. London, Paris and New York have all made big moves in recent years but they’re on such a different scale that it’s not a fair comparison.

The theory behind Wellington’s rapid rollout is that people will adopt cycling in much higher numbers once there is a connected network of protected bike lanes that cover most daily trips. To get there as quickly as possible, Wellington City Council is taking a speed-over-quality strategy using cheap plastic barriers and temporary but changeable designs. It’s a shift from the previous approach of expensive, stand-alone cycleways that don’t connect to anything (*cough*Island Bay*cough*).

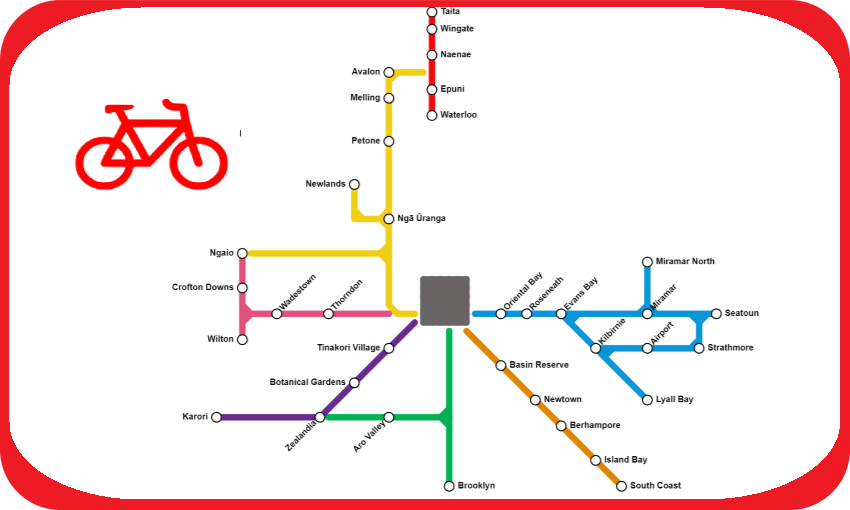

If the goal is a connected network, what will that look like and how far away is it? None of the maps on the council website answered the question. So I stayed up very late one night making my own and cross-referencing it against a pile of council traffic resolutions, because I guess this is my life now.

Map #1: The future

This is what Wellington’s commuter bike network will look like once all the cycleways under construction or in advanced planning stages are complete.

The biggest gap in the network is the city centre. Let’s Get Wellington Moving was supposed to build bike lanes in the CBD while Wellington City Council handled the suburban routes. Since LGWM was shut down, that part of the network has languished. Still, except for the final few streets, almost every suburb will have a direct and protected cycling connection to the city centre.

Map #2: The present

This map shows the current status of Wellington’s bike network. Black lines indicate cycleways under construction. Grey lines represent those in the planning and consultation phase.

The most significant missing piece is Te Ara Tupua, the seawall and cycleway from Ngā Ūranga to Petone being built by Waka Kotahi NZTA, which will connect the city network to the Hutt. Filling the gaps from Newtown to Island Bay and from the Botanical Gardens to Karori will significantly increase the total population the network reaches. Wellington City Council voted last week to defer the Wadestown section, putting the connection to Wilton and Crofton Downs in doubt.

Map #3: The Past

Five years ago, almost none of this existed. I went back through the timeline of projects to see what the cycling network looked like on this day in 2019.

Are you ready?

Are you sure you’re ready?

OK.

Here.

It.

Is.

The only part of the commuter bike network that existed in 2019 was a short protected lane on the busiest part of Oriental Parade, and an early version of the controversial Island Bay cycleway. The Avalon to Melling section is only listed here because it is part of the Hutt River Trail, though that is primarily a recreational route.

Wellington bike lanes completed since 2019:

- Beltway Cycleway (Hutt City Council)

Pito One to Melling (Waka Kotahi NZTA)

Wakely Road shared path

Hutt Road shared path

Ngaio connections

City to Botanical Gardens

Aro Valley connections

Brooklyn transitional bike lane

Newtown to city

Tahitai: Oriental Bay to Miramar (Waka Kotahi NZTA and Wellington City Council)

Currently under construction:

- Te Ara Tupua: Ngā Ūranga to Petone (Waka Kotahi NZTA)

- Kilbirnie connections

- Karori connections

- Thorndon connections

- Thorndon Quay

- Berhampore to Newtown

In the planning or consultation phase:

- Wadestown connections

Brooklyn permanent cycle lane

Te Motu Kairangi connections