It’ll probably be the longest and most difficult read of your life, but that’s all the more reason to do it. Lyric Waiwiri-Smith makes a case for delving into the final report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care.

Content warning: This article contains references to ableist language, physical, sexual and emotional violence, child abuse and neglect, and suicide.

Whanaketia – Through pain and trauma, from darkness to light, the final report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, is available to read in full here.

A day before the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care released its findings, a six-year labour of pain, deputy prime minister Winston Peters used the term “retard” to describe a question posed in the House. It was fleeting, unprofessional and indicative of Peters’ severely lacking vocabulary and social sensibility, but worst of all, it reinforced a notion laid out by the abuse in care report: that those at the top of society have historically had little compassion for anyone whose reality does not reflect theirs.

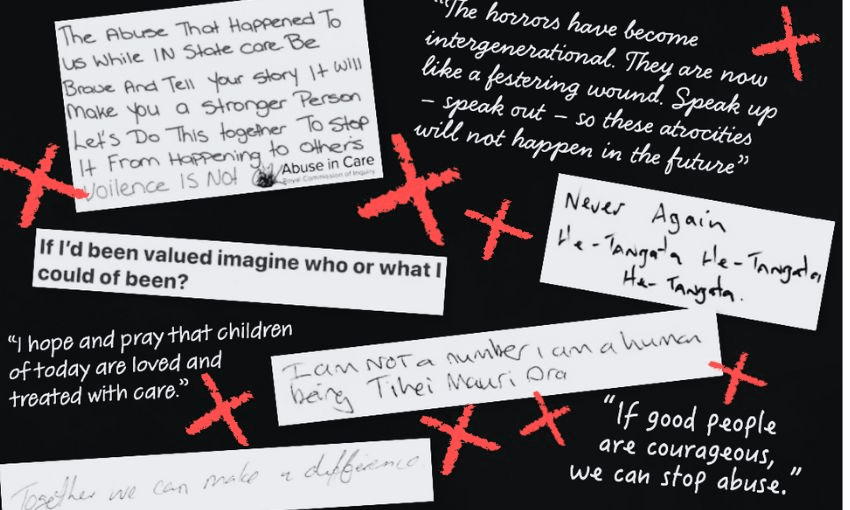

Covering 3,000 pages and, in hard copy, weighing 14kg, the abuse in care report will most likely be the longest read of any person’s life. It will also likely be the most harrowing: violence in every form you could imagine, from spiritual and systemic to physical and sexual, is presented in these pages. It also details abuse you couldn’t picture in your worst nightmare. But it happened, it’s a part of our history, and these survivors have relived their experiences now, some for the first time in decades, to bring to light a part of our society that has too frequently been thrown in the too-hard basket. The report doesn’t just bring justice to survivors by allowing their voices to be heard – it also exposes the ways in which care facilities, churches, Crown agencies and key figures of our society have directly or indirectly allowed this abuse and worked to silence these New Zealanders.

Maybe if they were heard the first time, we would have fewer people incarcerated and connected to gang culture. Maybe if we were brave enough to look at and ask ourselves why we allowed this to happen, we could’ve prevented this cycle of abuse and neglect sooner. We live with its effects now, as abused children don’t stay children for ever: they grow up, and are forced to assimilate into a society they have learned not to trust. Sometimes, these children turn into adults who we’re told we can’t trust either.

Split into 16 booklets, numbered zero to 15, the report covers the bases of why, how, when and where abuse was experienced, with five case studies focused on reports of abuse and neglect within the Jehovah’s Witnesses, at the Whakapakari boot camp, Hokio Beach School and Kohitere Boys’ Training Centre, Van Asch College and Kelston School for the Deaf, and the Kimberley Centre. Survivor experiences are dotted throughout the booklets, though the final, the 15th, is dedicated solely to these stories.

The first four parts of the report lay out the circumstances, nature and extent of the abuse and neglect experienced in care, the reasoning for the report and its methodology, and recommendations to the government to ensure environments such as these are eliminated from New Zealand society. Part five of the report, titled Impacts, details the effects these decades of abuse have had on victims, which the reports estimates to be between 113,000 and 253,000 children, young people and adults between 1959 and 2019. This is around a third of people in care settings over this period, and a disproportionate number of these victims were Māori.

As detailed in the report, time in care has provided a direct pathway for many survivors to gang membership or imprisonment, particularly those who are Māori or Pasifika, as well as sex work. The camaraderie and protection offered by gang life felt far more meaningful for some survivors than the degradation experienced at the hands of church or state, and the rampant abuse ultimately became normalised, with these learned behaviours sometimes continued into adulthood. Gang members and prisoners often seem to us as shadowy boogeymen; we have an idea of how they’re shaped (big, imposing, strong) and what they represent (fear, violence, criminality), and these ideas are reinforced by the media and government. In reading this report, the veil is lifted, the child inside of the “boogeyman” is looking back at you and saying “I was scared of a bad person, too.”

In his witness statement, survivor Poihipi McIntyre wrote: “to survive [Kohitere] I had to become a bully and use violence against others. This changed me. I lost empathy and became numb to witnessing and engaging in physical violence. To me, Kohitere was a training ground for jail.” A separate statement from survivor Jesse Kett paints a similar picture: “I first went to jail when I was 17 years old, for burglary and arson. I was in Waikeria prison for about nine months. To me it was like a holiday compared to Waimokoia. It was also better than most foster homes because everyone was treated and fed the same. I think I’m quite institutionalised because I don’t mind being in jail.”

The generational effects of abuse and neglect in care are far-reaching and complex, and it’s for these reasons the report recommends a $10,000 compensation be made to family members who have been cared for by survivors. The account of one faith survivor, whom the report named Mr JP, summed up the cyclical effects: “I have not been able to find my whakapapa. I had hoped to let my son know so that he could one day let his children know. But my son is dead now. He committed suicide in prison.”

The report’s sixth part uses a te Tiriti o Waitangi and human rights lens to unpack the levels and effects of abuse and neglect in care. It details a widespread loss of culture and language for Māori and Pasifika, and how this has impacted victims. The following instalment, part seven, looks at the factors that allowed abusive and neglectful environments to thrive in care. At 336 pages, it is one of the longer sections of the report, and perhaps the most difficult to read, covering the extent to which this abuse was covered up, the environments which allowed this behaviour to thrive, and the many ways these children were failed.

Christina Ramage’s survivor experience sits in part seven. She describes a lifetime of sexual assault and abuse, and how this was taken advantage of by those who should have kept her safe: she was raped by doctors while confined in a straightjacket, and later given a nonconsensual abortion by a nurse after being raped by a psychiatrist. Renée Habluetzel’s experience is here too: under the thumb of Mrs Miles of Christchurch’s Little Acres Children’s Home, she was given violent beatings and was made to feel like an object.

Reading this report may very likely make you feel hopeless, angered, saddened and full of grief for the futures that were never realised. But there’s something else to take away from this as well: that, despite incredible adversity, compassion and healing is possible. Some survivors have found forgiveness and understanding, and others haven’t – that’s their journey – but as readers we can all learn how to act compassionately towards those whose lives have been made difficult by forces larger than them, and the lasting effects of this, whether it has provided a pathway to jail or an escape from the care system, where abuse still occurs. We have to be willing to listen.

These stories are long and confronting, so take care when you read this report. Linger on the karakia at the front of each booklet, feel the mana within the witness statements, learn what abuse and neglect looks like in all its forms, and encourage others to do the same, so that no New Zealander faces these horrors again.

It’s the same sentiment present in Te Pāti Māori’s Debbie Ngarewa-Packer’s call for an apology from Peters over his mindless use of an ableist slur in parliament, a place that has allowed a culture of abuse and neglect to thrive, where leaders of ministerial departments that have willingly swept survivors’ stories under the rug decide on the future of Aotearoa. “The history of the word ‘retarded’ is bad enough to be hearing in this House, in fact people have endured years of abuse because of that very name,” Ngarewa-Packer said. “It is unparliamentary for a minister of that seniority, and age group, to be saying that in the House.” At speaker Gerry Brownlee’s request, Peters withdrew his word. If we don’t recognise what behaviours have led us here, we’ll never change.

Where to get help

Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 (0800 LIFELINE) or free text 4357 (HELP)

Youthline – 0800 376 633, free text 234 or email talk@youthline.co.nz or online chat

Samaritans – 0800 726 666

Suicide Crisis Helpline – 0508 828 865 (0508 TAUTOKO)

Help (for survivors of sexual abuse) – 0800 623 1700

Male Survivors Aotearoa – 0800 044 334

Snap (Survivors network of those abused by priests)