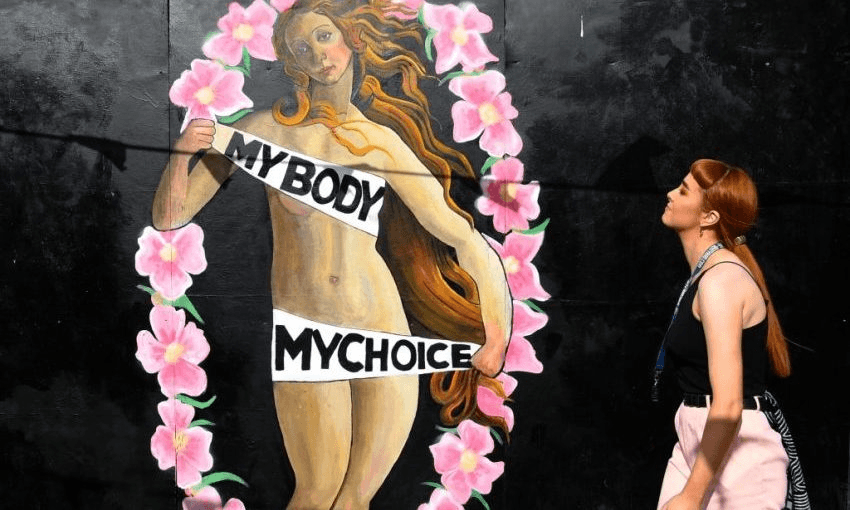

Ireland appears to have delivered a landslide victory for the repeal of the amendment outlawing abortion. It show it is time for the state to trust women to make that choice for ourselves, writes Irish New Zealander Noelle McCarthy

We thought it would be close. The outcome of yesterday’s vote on whether or not to repeal the 8th amendment to the Irish constitution, which gives equal rights to life for a mother and “the unborn” – in effect outlawing abortion for Irish women – was never a forgone conclusion. “This is still a deeply catholic country” my best friend Edel texted yesterday, alongside a photo of a man standing outside the Dáil (Irish parliament) with a statue of the Virgin Mary that she’d snapped on her way to work. All a bit Father Ted, but a few of our mutual friends had already said they were voting No. One had had an abortion and regretted it, another thought it was none of his business as a man to tell women what to do. My sister Viber-ed from Cork last week, shocked about the number of women she knew who said they were voting no: “There’s a younger generation saying ‘it gives whores a way out’.”

At the time of writing, an Irish Times exit poll suggests the Yes side in the Irish abortion referendum will be 68%. I didn’t see it coming, not a landslide, nothing so thumpingly unequivocal. Edel has been leaving Whatsapp voice messages since eight o’clock this morning, each one more jubilant, and yes, drunker, than the one before.

“Wake up, wake up! Are you seeing this?“

“I can’t believe it. Wake up! WE WON!”

“UNDER HIS EYE! NO YOU FUCKERS! NOT ANYMORE!!”

The Gilead reference might feel like hyperbole, but when you consider the 8th amendment to the Irish Constitution gives an equal right to life to a woman and “the unborn” in her uterus-regardless of the circumstances of conception-effectively outlawing abortion for Irish women even if they’ve been raped, even if they may die as a result of complications in the pregnancy, you can see where she was coming from.

And there’s more than a whiff of Gilead in the policing of women’s bodies by the Irish church and state that led to the passing of such a dangerous and restrictive clause in the first place. I was only five years old when the 8th went through in 1983, but my mother was 30. She had already grown up in a country where catholic doctrine provided a solid moral basis for controlling women’s sexuality, which it did with the energetic collusion of the Irish government.

The discovery last year of the skeletons of hundreds of babies in a septic tank on the site of a disused orphanage in Galway showed us exactly how the Irish state dealt with the children of women unlucky enough to fall pregnant outside of marriage. A mass grave that exposed the lie of all that “sanctity of life” chat. That place was still open when my mother was a teenager. Dark secrets like that abound in Ireland, shut up in the heart of families who can’t or won’t share them for fear of the shame they would bring.

The stories of women in my family are not mine to tell on a day like this, but the #TogetherforYes campaign felt like a shared rejection of that culture of shame that has scarred Irish women for too long, from the Magdalene laundries and the forced adoptions, all the way up to the women of my generation who booked a Ryanair flight to London and thanked our lucky stars we had the money to do so. Well, they got back on the Ryanair flights this week, the women of Ireland and they came home and they voted. They voted to change a status quo that was dangerous and restrictive and deeply unfair. They voted so that their daughters won’t have to carry the shame and the guilt that was foisted on their mothers and their grandmothers and came down to us when it wasn’t ours to bear.

THEY’VE ARRIVED. Now that’s what we call a welcome party. #hometovote @Together4yes @DublinAirport pic.twitter.com/e7TgucTONM

— London-Irish ARC (@LdnIrishARC) May 24, 2018

My hope now is that those who oppose abortion on religious and moral grounds will find it possible to live in this new Ireland. I don’t believe their worst fears will be realised. Yes, there is a gravity to the choice the Irish people have just made. But having grown up in a country where getting pregnant outside of marriage was the direst of fates, how can I not rejoice that with this vote, this thumping, resounding, big hearted Yes, the state is now saying it trusts us to make that choice for ourselves.

This might be a good time for New Zealand to do the same.

The Bulletin is The Spinoff’s acclaimed, free daily curated digest of all the most important stories from around New Zealand delivered directly to your inbox each morning.