The third installment from our team film critics swarming the cinemas of Auckland and Wellington for the 2018 NZ International Film Festival.

See also:

Birds of Passage, First Reformed, Disobedience, 3 Faces

In the Aisles, The Image Book, Apostasy, Brimstone and Glory

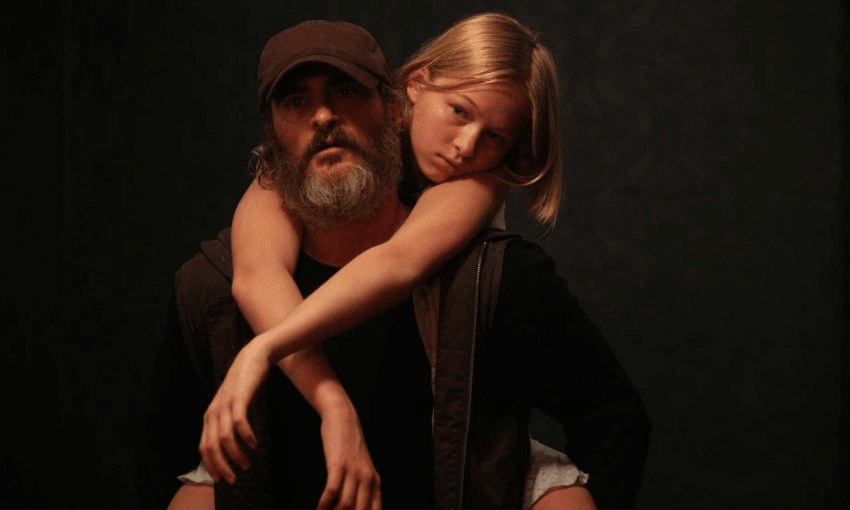

You Were Never Really Here

Not everybody likes Lynne Ramsay’s brand of cinematic disorientation but it works pretty damn well for me. Adapted from Jonathan Ames’s 2016 Reacheresque novella, You Were Never Really Here gives the finger to fast-paced genre heroics as seen in such pulp exemplars as Besson and Morel’s ‘rescue the girl’ trope-fest Taken. And yet Ramsay’s film is as tensely thrilling as any action movie you’d care to name. If a little less fuck-with-your-head than 2011’s divisive school killing drama, We Need to Talk About Kevin, You Were Never Really Here is designed, head-to-toe, to disorient the viewer: from the swirling, focus-shifting camera in the film’s opening; to Jonny Greenwood’s perfectly matched aural dissonance; to an edit that eschews voyeuristic payoff in favour of observing character response to the physical and psychological violence occuring.

When action is displayed, it is visually filtered in some way, such as a fantastic sequence viewed via building security camera monitors. Joaquin Phoenix, embodying another PTSD afflicted veteran, proves again that his face and posture are as valuable onscreen as his delivery of dialogue. Unfortunately all other characters get short shrift but Phoenix is equal to the task of carrying the performance element of the film. I’m not sure there’s a lot of “thematic takeaway” to be had from You Were Never Really Here but that is 90 minutes I’d happily spend in front of the cinema screen again.

Jacob Powell

Kusama – Infinity

Let me preface this by saying I talked to several people who liked Kusama – Infinity afterwards, and that my approach to watching documentary is probably a bit different from theirs. If you’re showing up to see some Yayoi Kusama art and learn a bit, you get that, and she’s an interesting and provocative character. But there’s a difference between a film about a good subject and a good film. Personally, I want something more than an hour of flipping between a Wikipedia entry and a Google Image search would provide, and for the most part Kusama – Infinity fails that test. I’m a casual fan of the Japanese art legend but no expert, and was hoping for a bit of a look inside, but it’s clear that filmmaker Heather Lenz had limited access to Kusama, instead leaning on a parade of American curators to assert her worth as well as lengthy sections of her autobiography printed as subtitles onscreen. The early years are an especially grueling stretch, with about fifteen different anecdotes about how Kusama’s parents didn’t support her.

Things can’t help but perk up when she gets to New York, and it’s here that Lenz gradually reveals her locus of interest: Kusama as a groundbreaking visionary whose innovations were constantly co-opted by male artists, leaving her forgotten. It’s a compelling argument, but for such a singular artist to be oversimplified as a victim of patriarchy feels frustratingly reductive, especially when Kusama’s mental illness is an inescapable part of the narrative. The back half of the film sputters along as Lenz and her no fewer than 6 credited editors quickly skim their way through her next 40 years, as Kusama’s reputation is restored and she becomes “the world’s most successful artist” (note: this claim has not been independently verified). And yet, having been inside a Kusama room myself, I felt like Lenz never really fully captured her magic. Replete with smothering score, uninspired storytelling, and cinematography that veers between functional and incompetent, Kusama – Infinity is as frustratingly pedestrian as its subject is visionary.

Doug Dillaman

Transit

Master dramatist Christian Petzold nails it once again with this timely, temporally transplanted story of ethnic cleansing in occupied France. A general tenor of mistrust and unease permeates the hallways and byways of Petzold’s Marseille as his characters warily circle each other; plans to escape or inform not far from mind. Franz Rogowski’s central performance as Georg, a German Jew seeking to leave France as the country’s borders snap shut, is perfectly pitched. Evincing a tangled mess of cynicism, empathy, and self-preservation, Georg takes advantage of an administrative mistake to assume the identity of a recently dead writer in an attempt to gain the papers he needs to exit the country. Petzold complicates matters for Georg in the form of the beautiful Marie (a very fine showing from Paula Beer) who keeps crossing his path while hunting for her estranged husband, and also Driss, the young football mad son of Georg’s friend who begins to see the older man as a father-substitute. How can Georg possibly help all these others when he can barely keep himself out of the harm’s way?

Transit is narrated in the third person by a character we meet late in the film, creating a measured procedural feel. The filmmaker and his regular cinematographer Hans Fromm make great use of shadow and the spaces between buildings to lend a noirish visual tone to the preponderance of bright, daylight settings. Petzold ranks among those filmmakers—cf. the Dardenne brothers and Asghar Farhadi—whose work revisits the same thematic (and even narrative) territory, whilst remaining grippingly poignant. The German writer-director’s story construction, dialogue, and direction of actors is as immaculate in Transit as it was in Barbara and Phoenix.

Jacob Powell

Piercing

Marrying pitch-black Ryū Murakami source material with a luxuriously tactile Giallo visual sensibility— garish colour tones; fantastic use of contrast, light, and shade; physically and metaphorically claustrophobic hallway sequences; a tight focus on physicality &c.— Borderline films alumnus Nicholas Pesce creates an arrestingly subversive psycho-thriller in Piercing. A deliciously droll cat and BDS-mouse tale, the film spools out a clever, if slightly opaque, short story (and at a fleet 81 mins it ain’t no hard slog). The sadistic symmetry the central pair engage in put me in mind of Kim Ki-duk’s The Isle (2000), another noteworthy Incredibly Strange pick from festivals past. Any narrative thinness is counteracted by perfectly toned performances from Christopher Abbott and Mia Wasikowska as they circle awkwardly around each other with surprising, amusing, and disturbing results. Piercing could be a fun date movie… for the right (or should that be “wrong”) couple!

Jacob Powell

Terrified

“There are two ways to look at everything,” notes one paranormal investigator in the Argentinian horror film Terrified. Indeed. Here’s one: as a horror fan, I found the first half of the film – after a strong beginning, to be fair – relatively weak sauce. I’d expected a zombie movie from the still, but it’s aiming for something closer to The Conjuring; however, the interminable chats between cops and said investigators hew closer to a straight-faced Wellington Paranormal set in Argentina. All is forgiven, however, in an absolutely dynamite second half that earns the film its title. Writer/director Demián Rugna – also responsible for the terrific score – reveals an uncanny flair for perfectly-executed jump scares and genuinely unsettling imagery as the full extent of what lies under the skin of this bucolic suburban Argentinian street unfolds. It’s not likely to enter the pantheon, but enjoyed with a crowd, Terrified is still a good scary time at the movies.

Here’s another way to look at it: there’s a good chance most Kiwi horror audiences aren’t familiar with Argentina’s military dictatorship from 1976 to 1983, and particularly the desaparecidos, people unofficially “disappeared” by the government. (And I wouldn’t have been, either, without a tip from horror guru Erin Harrington). But it’s this context that gives Terrified its potent sting. An early scene where an investigator suggests that a policeman falsify his “official” report (regarding a seemingly undead child) recalls the title of a famous Argentine film on the topic, The Official Story. With this in mind, odd details start to make sense, such as why all the paranormal investigators are old enough to be complicit in these crimes and why all those effected are a generation younger, or why one of the investigators is American. (Do I need to even mention that the US was involved in propping up that dictatorship?) Expertly integrating its metaphor into its supernatural conceit and ferociously pointed up until its final frame, Rugna’s Terrified provides a potent argument that William Faulkner’s aphorism is universal. The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

Doug Dillaman

Yellow is Forbidden

I think one of the most interesting questions we can ask of fashion is, ‘What is a dress?’ This question becomes more acute when the dress can not be worn. Chinese designer Guo Pei’s couture works are the perfect subject for exploration of the relationships between form and function. An imaginary binary often used to define the boundaries between art, craft and design. Early in Pietra Brettkelly’s Yellow is Forbidden we see images of models falling and struggling to wear Guo Pei’s heavy and elaborate dresses.

Although Yellow is Forbidden takes its shape in time from the build-up to Guo Pei’s 2017 spring-summer collection and her pursuit of acceptance from Paris’ Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, Brettkelly’s genius lies in her layering of second and third narratives in theme on top of this story. Brettkelly creates tensions with Jake Bryant’s stunning images which play wealth with poverty, business with art, old Paris with new China, communal labour with the work of the artist, even Communism with Capitalism. The film is roomy and fluid, we move freely with Guo Pei through her work, she’s often laughing, then, in one scene, we’re close up under an embroidery frame observing the squeak of a single stitch in a garment of a billion stitches. Over the frame works one of the 300 embroiderers who produce Guo Pei’s garments. While the film doesn’t overtly judge the contradictions of fashion it doesn’t allow the audience to settle in any comfortable or conventional view of the industry.

Yellow is Forbidden played at the Gala Opening of the Wellington NZIFF and Brettkelly spoke, wearing a Guo Pei gown, about the magic that happens when someone says, “Yes.” Yellow is Forbidden is a stunning film with master craftspeople at its helm who can order all that “yes” brings in beautiful and provocative ways.

Pip Adam

The Miseducation of Cameron Post

Almost 20 years after But I’m a Cheerleader, it is a sad fact that there are still films to be made about gay conversion camps. The Miseducation of Cameron Post, based on a young adult book from 2012, is actually set in the early 90s – still the time of cassette tapes and no internet for queer kids to seek self-validation on. In an unnamed, small town in America teenage Cameron is caught with her girlfriend and summarily shipped off to an evangelical residential programme where she joins a mixed group of teenagers who are either trying earnestly to turn themselves straight or just trying to keep each other sane.

This is a much more serious and realistic film than the satirical But I’m A Cheerleader. That’s not to say there isn’t humour to be had in the crazier statements of the evangelicals trying to pray away the gay, and while Chloë Grace Moretz’s Cameron is able to maintain her rebellious disconnection the audience can laugh along. But eventually the insidious tearing at her sense of self starts to break her and you can feel the film start to build towards tragedy.

There’s a great turn by Jennifer Ehle as the certain of her methods camp director, she bears a startling similarity to the theatre director Evangeline in Madeline’s Madeline, also playing at the festival. There’s also a nod to one of NZIFF’s retrospective films this year, Desert Hearts, just about the only decent, non-tragic lesbian film Cameron and her friends would have had access to.

I’m a little surprised the film took top honours at Sundance, I’d have classed it as really good rather than great, but I am glad it’s available for a new generation of queer kids to see. And bless the director Desiree Akhavan for the hopeful ending. For the record, gay conversion therapy is legal in New Zealand. Don’t think these things don’t happen here.

Aquila