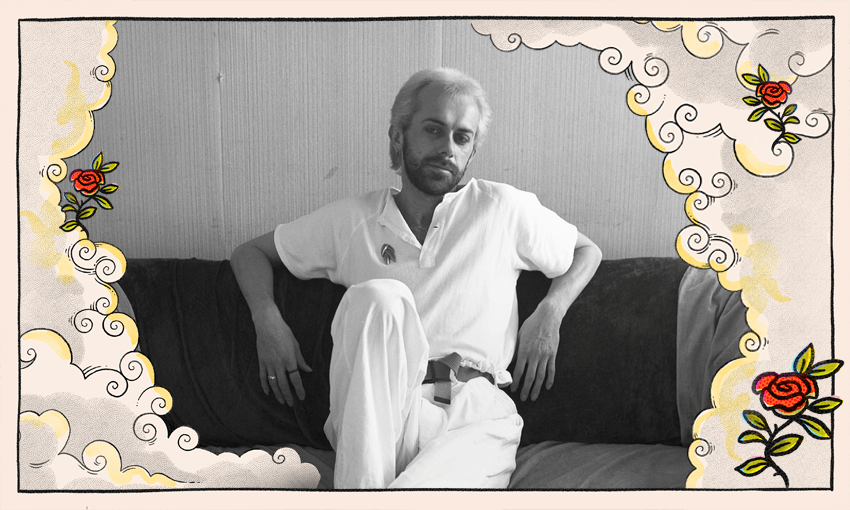

The photograph is striking and beautiful, but also disturbing – a reminder that my love for John was often entangled in shame.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

In the spring of 1980, in Dunedin, shortly before his death, someone took a photograph of my brother John. The photograph doesn’t look out of place today, but when it was taken it wasn’t ordinary. It shows John – in a white, Japanese styled, loose-fitting top and trousers, a bleached white crew-cut, his black beard closely cut – as a fearlessly gay man, at a time when his sexuality was illegal.

The photograph is both striking and beautiful, but also disturbing – not only for it being taken in such close proximity to his death, but as reminder that my love for John was often entangled in shame. My mother gave me the photograph years ago, and I have kept it since in the room where I read, tie fishing flies and sometimes write, where only those few who enter could see it.

I hadn’t thought about its provenance until my wife asked me if I knew who had taken it. She was reading Paul Moon’s book on the life of photographer, Ans Westra, and based on the book’s cover photograph of Westra, she suggested the image of John might have been taken by the same person: Adrienne Martyn.

That the photographs were taken by the same person was an improbable coincidence, but after a few days of having the Westra book near me I began to think she might have been right. An essence of the photographer appeared to infuse both. Still, when the frame was removed, it was a surprise to see Adrienne Martyn’s name on the back of the image.

I contacted Martyn, who now lived in Wellington where she continued to photograph people and buildings, asking whether she remembered the session with John, and if she had retained any of the negatives or proofs from it. Martyn replied right away – she had both proofs and negatives from the session and a clear memory of it. She had known he died shortly after the images were taken.

We exchanged emails about John and the images, and within a few days I had received two stunning new prints: a new one from the session, and a fresh image of the original, the one she told me John chose. The exchange and the 36 images she shared with me brought him close, in the most unexpected way.

The decades have stretched out since John’s death, but I keep his presence near me. On one wall of my room are eight photographs taken by him, and on the bookshelf are several of his books. I knew he had an interest in photography, and that he had worked on the film about the Burton Brothers – early New Zealand photographers – but it wasn’t until 20 or so years ago, when I took some of his photographs out of a folder that I realised what a fine eye he had.

As best I can tell, because he wrote nothing on the back of them, they were taken at the Ngaruawahia Music Festival, in 1973. They are sensual images that capture the essence of the era, full of love and the energy of youth, and they leave me wondering what happened to the beautiful people he caught on film.

The books I looked through again recently, hoping to find something of John on the pages, but found no marginalia that might have told me something of his thoughts, and when I held them to my nose and flicked through the pages all I could smell was the mustiness of old books.

There is something of him in the choices though. Some, like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Crack Up and Under A Glass Bell by Anais Nin, are set in the era of Art Deco and jazz he admired. Others, like The Wild Boys by William Burroughs and Prater Violet by Isherwood, and books by James Baldwin are written by authors who were gay. John owned these books before it was clear to others that he was gay, and looking back, I imagine they offered him a sense of familiarity in the unfamiliar Southland of his youth.

The Gore of the 1950s and 60s was a conservative town in a conservative part of the country. We knew everyone who lived on our street, and there was only one house on it that we might not have been welcome to visit, unannounced. Few people or houses stood out from the crowd. It reads like a cliche now, but the boys and men played rugby, drank Speights and some bet on racehorses. Most of the men cycled to and from work, as did the women, who worked in offices, schools and shops in the brief time between leaving high school and getting married, young. Couples stayed married, although some women mysteriously left town to spend time away at Seacliff where they recovered from illnesses that went unexplained.

This caring community suited those that conformed but was a tough place for those like John who were born to be different.

John was born in Gore on the 26th of February 1952, three years and a couple of months after me. From then, until I moved, thirteen years later, into the converted garden shed adjoining the hen house in our backyard, we slept in beds just an arm’s length apart. We were, for those years, almost as close, and as far apart as it was possible for two boys to be.

I have many photographs from our early life in Southland, showing us together, some by rock-pools while on holiday in Riverton, and in front of our house in Wentworth Street; one with my pet-lamb, Frisky, standing with us on a daisy spotted lawn. There is another of us in Christchurch when we are older, a trip that would have been a major expedition at that time of our lives. In that photograph, and many others from our early years, we are wearing matching clothes; ironic, given how the way we dressed changed over the following years.

I sometimes wonder if the photographs have played a part in stealing away my memories of those early years together, because the events themselves are mostly locked away in an unopened vault in my memory. I remember the first trout I caught in the Mataura River when I was four, but nothing of John as a baby, suggesting perhaps that being self-absorbed is the natural state for a child.

I recall us playing with toy farm animals on the carpet at the end of our beds in the room we shared with Paul, our much younger brother. We built fences for the cows and sheep with little brown bricks, and often sat for long periods, constructing a make-believe world of farms and happy families. The sessions often ended in chaos, with me stomping my animals into the fences, followed by animals being thrown, arguments with Mum about who started the fight, and tears – mostly from John.

The first concrete memory I have of John is one that highlighted our differences, and evoked emotions in me that surfaced later in our lives. On that day summer sun shone on a crowd gathered in front of a stage set up beside a line of leafy poplars on Hamilton Park, not far from our home in East Gore. I believe the events of the day were to celebrate the renaming of what had been called The East Gore Domain, to Hamilton Park. It would make the year 1957; I would have been eight and John soon to turn five.

A talent quest was underway, and I stood beside Dad and Gran and Pop Hicks, while the show took place. I had been told John was to make an appearance in the contest, and he and Mum had gone to get him ready for the performance. Contestants danced, sang, played the guitar and piano, and the crowd clapped and shouted support.

Eventually, after a long break between contestants, I saw the curtain beside the stage ripple with movement, and a little figure almost make it through, before retreating. The woman at the piano started playing, then stopped, and looked back at the curtain. A murmur, like wind rustling leaves, went through the crowd as I stretched to see what was happening. The piano played again, the curtains parted and out came John, pushed along by two arms that reached out from behind the curtains.

He stood in the middle of the stage, tiny and alone, wearing nothing but a grass skirt and an Hawaiian lei around his neck. The piano player stopped. A ripple of amusement lifted from the crowd, and the crackly sound of a record came through the speakers. John looked like he was about to run until a voice called to him from behind the curtain and he began to dance. His hips shook to the sound of Hawaiian guitars, and his arms and fingers, held to the audience, quivered to the music.

I looked up at Dad, worried about what he might be thinking, but he stared at the stage without expression. I was shocked at John’s bravery, but I was also red-faced with embarrassment. When the record finished and the dance stuttered to an end, some in the audience clapped, and many laughed. I slunk away, not wanting to be known as the brother of the little boy in the grass skirt, dancing.

By the time we were at high school our differences were obvious, although the words to describe what lay behind them didn’t come until we lived together in Dunedin. In the last years we lived in Gore, I fished for trout, played rugby, ran on the track, delivered newspapers, and worked after school with Pop Hicks at The Southland Farmers Coop, while John biked across town to practice ballet with the few brave enough to follow their dreams, irrespective of the consequences.

Our lives were upended by the death of our 41-year-old father in 1966. Mum took a part time job to help keep the family afloat, and in 1967 I left for university in Dunedin, while John also moved away, to Dunedin, then Wellington and Auckland. He lived an exuberant life in his new community, though always shadowed by his challenging early years, and the illegality of his sexuality.

John died in the spring of 1980 of an asthma attack while involved in the filming of The Race For The Yankee Zephyr. Filming of the movie stopped for three days after his death, and some of the cast, including the director, David Hemmings—who earlier starred in Antonioni’s movie, Blow Up, about a photographer—came to his funeral in Gore.

From my first memories of him, until he died, aged 27, I loved him, and admired his bravery in the face of his heroin addiction, and the drowning of the partner he loved. There were times when I confronted those who mocked him for being different, but there were times also when I acted like the boy in the park, who turned away from him in shame. I can forgive myself for these failures now, but they play a part in my desire to keep my memories of him alive, as I live my most fortunate life.