It’s not often that people are interested in tsunami, so while interest is high, let an expert tell you every, single, thing you should know about them.

What happened?

On Wednesday, a large magnitude 8.8 earthquake occurred near Russia. Large earthquakes that occur on faults have the potential to cause a tsunami by the sudden movement of the ocean floor, causing a lot of water to move very quickly.

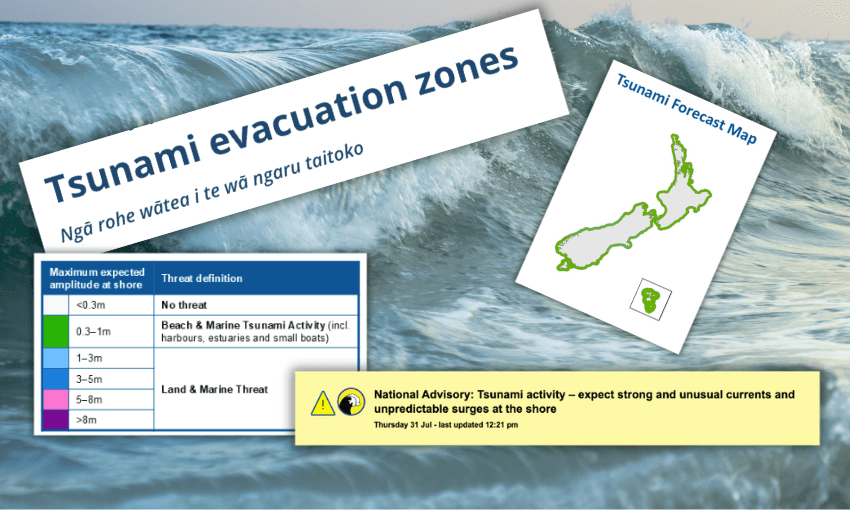

The National Emergency Management Agency initially advised that the earthquake was being assessed, then they advised that there was no tsunami to New Zealand. They later advised that they were reassessing as the earthquake magnitude had been upgraded.

Then they issued a “Tsunami Activity National Advisory” for beach and marine tsunami activity and sent out two emergency mobile alerts, one on Wednesday afternoon and one early this morning.

The first currents and surges here in New Zealand are unlikely to be the largest and are expected to continue over many hours. The advisory stands until it is cancelled.

A tsunami advisory is different from a tsunami warning, which is when there is a tsunami threat to land, e.g. waves come onto land. That’s when evacuations come into play.

Some may have felt frustrated, others reassured by the alerts, especially those who recieved multiple alerts because of the technical issues. The real challenge with warnings is that everyone has a different level of risk tolerance including those sending the alerts. There are operational guidelines but also other pressures to consider. It’s a tough balance to avoid the “boy who cried wolf dilemma”.

How do we classify a tsunami?

In Aotearoa, we classify tsunami based on the travel time between the source of the event and us. This matters because it determines the type of warning we’ll receive. The three official classifications are:

- Local source tsunami – Less than one hour travel time (e.g. a large earthquake occurs on the Hikurangi Subduction Zone)

- Regional source tsunami – 1-3 hours travel time

- Distant source tsunami – More than three hours travel time (e.g. a tsunami triggered near Russia)

There’s also lake source tsunami – less than one hour travel time.

What affects travel time?

Several factors influence how fast and how far a tsunami travels, as well as the areas it impacts:

- The location of the earthquake or triggering event

- The amount of water displaced

- The shape and features of the ocean or lake floor

- The shape of the coastline and the surrounding land

- Your location relative to the source

A distant source tsunami gives our scientists far more time to model the tsunami and monitor the waves as they travel across the ocean, giving us more time to understand how it may impact us in New Zealand and provide the appropriate warnings.

What warnings might we receive?

There are three types of warnings: natural, official and unofficial.

The ultimate natural warning is a long (longer than a minute) or strong earthquake (difficult to stand up in), once the shaking stops, immediately evacuate to high ground or inland (by foot or bike). Do not wait for official advice.

For a regional source tsunami, Civil Defence may (it’s a tight timeframe) use tools like emergency mobile alerts, social media and radio to inform everyone.

For distant source tsunami like the one this week, Civil Defence will use a range of tools like emergency mobile alerts and media to keep everyone up to date.

I get asked a lot about tsunami sirens. They’re only used in specific locations, as tsunami risk looks different in each region. Different locations have different levels of exposure to local, regional, or distant source tsunamis, and so different tools will have differing levels of effectiveness. That’s why there’s no one-size-fits-all approach, and we use a range of warning tools.

Why do we always hear about ‘long or strong, get gone’?

Local source tsunami are a higher life safety risk, as they provide less time for us to evacuate.

Even if you can’t make it outside your evacuation zone after an earthquake, you may already be outside the inundation area, where the waves have come onto land.

Moving further inland or uphill increases your chances. Our evacuation maps are typically based on multiple scenarios, meaning that what may inundate one area in one scenario may not inundate a different area.

PS, if you don’t know where the evacuation zones are, I totally recommend checking them out now. Not later now, I mean actually now (like stop reading this article now).

How big will the wave be today?

Firstly, a tsunami is not just one wave, it’s a series of waves. Getting back to the question, it depends on the size and location of the earthquake and the shape of the seafloor, so there’s no single answer.

What is important to know is that the first wave may not be the largest, and waves may continue for hours. That’s why we say wait for an all-clear. Also, in some cases, large aftershocks can trigger additional tsunami waves, which is why it’s important to stay evacuated until the all-clear is given

Where can I check if I need to evacuate?

It’s important to know whether you’re in an evacuation zone ahead of time. Maybe check now? If you don’t already know. Your local tsunami evacuation zones are also on your regional Civil Defence or council website.

Where should I evacuate to?

Simple answer, away from the coast, and inland or uphill.

Ideally, to friends and family if you can.

I 100% recommend practising your tsunami evacuation route ahead of time. At the very least checking the maps (again, do it now), and thinking about where you can evacuate to, and different possible routes to get there in case your original route is blocked.

- Know your zone

- Practice your evacuation route

- Make a plan

- Create a grab bag.