In 1981, New Zealand runner Anne Audain accepted prize money for winning a race. In doing so, she changed the status of professional sports all around the world.

Anne Audain always led from the front. In middle distance running, more so than the shorter races, strategy will often beat raw speed. Drafting behind the leader, or holding back until the right moment to strike, are tactics frequently employed to save a runner’s legs for a strong finish. Audain never did this. Her strategy was to go out in front and lead the whole way. This strategy not only worked on the track but in life, where Audain led from the front in changing professional sport forever.

Audain didn’t hesitate when signing the entry form. It was for a 15km road race in Portland, Oregon. The course was hilly, a terrain that suited Audain. Thousands of runners had entered and the winner would have bragging rights for a long while. They’d also have $10,000.

Audain won the women’s race. For her efforts she received a $10,000 cheque and a lifetime ban from the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), the global governing body for the sport of athletics.

In signing the entry form the night before the Cascade Run Off, alongside a number of the world’s top runners including fellow New Zealanders Lorraine Moller and Alison Roe, Audain knew she could be signing away her amateur status. And in 1981, with the Olympic Games and World Champs still classified as amateur events, an amateur status was the only status worth having.

Now living in Idaho, Audain has no regrets about the decision she made 38 years ago. Besides, all the men were being paid already, though not officially. “I would travel with the guys from here to Europe and be on the European track circuit,” said Audain on a recent trip to New Zealand. “I knew all the under the table payments that they were all getting, the male athletes were getting good money.

“I didn’t begrudge them in the least, but if I ever got the chance to earn money out of running, I was going to take it too.”

Road races on the European circuit would offer appearance fees under the table to the top competitors, keeping the talent concentrated and allowing the sport to maintain its amateur status. So when rumours began circulating that someone in America was not only offering substantial prize money, but paying women too, Audain flew over immediately.

The money was put up by Phil Knight and his new shoe label Nike. Running for recreation experienced a boom in the 70s and road races were growing more and more popular, with Nike leading the way in putting on events for all runners, regardless of speed. They offered prize money to the top runners, wanting to entice the world’s best into their races and, hopefully, into their shoes. But at that point, running was governed strictly by the IAAF, and to accept money for it was to go against the spirit of running, and the rules of the IAAF.

Three years earlier, before the inaugural Cascade Run Off, the Amateur Athletic Union demanded that any and all entrants join the union as amateurs before racing. The organisers refused, saying their race was for all runners, no matter the affiliation. This belief, combined with the accessibility of running for recreation, led to road racing being perhaps the only sport in the world in which a genuine amateur from down the street can enter and compete in the exact same race as some of the fastest runners in the world.

Thanks to the Cascade Run Off, and runners like Audain who took the prize money, the state of amateur – or “shamateur” – athletics was shattered.

Audain accepted her ban and wasn’t able to run in any official meets in New Zealand that summer. Some organisers even sought to bar her from attending as a spectator. But an international ban didn’t stop her from training. Audain kept getting faster and ran a world record 5000 metre time at Mt Smart Stadium in March of 1982. The record was recognised by media around the world but not by the IAAF. More importantly, it was recognised by her fellow runners.

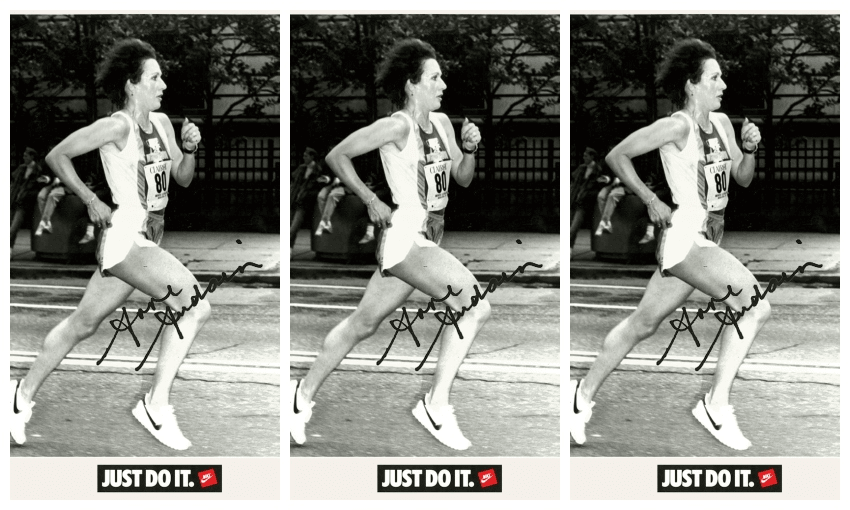

Audain didn’t hesitate in signing the napkin. It was Atlanta, Georgia, in 1981, shortly after her win at the Cascade Run Off. The international ban was in place, so Audain was running in America full-time, where race coordinators were happy for her to compete and, almost every time, take home the prize money for winning. She was the star of the road racing circuit, and Nike was looking for its first stars to endorse. Audain’s contract was for $400 a month. “I thought I was really rich with that,” she remembers. “because I was starting to get some prize money too. So getting $400 a month from Nike was just so exciting.

“I believe I was the first woman to sign an official professional deal with Nike.”

After breaking the world record, albeit unrecognised at the time, Audain was treated to a reserved acknowledgement in her home country of New Zealand and a hero’s welcome at the Nike headquarters in Oregon. She signed a new contract that took her from $4800 a year to $40,000, which, “for a young girl from New Zealand, that was, I was like, oh my Lord, I couldn’t believe it.”

On top of the Nike contract, Audain signed an equally lucrative deal with Diet Pepsi, and continued to earn prize money around the America road circuit. For a few years in the early 1980s, Audain was earning up to US$150,000 per year as a runner. Adjusting for inflation and currency conversion, that’s half a million New Zealand dollars. Very few, if any, distance runners today would earn that much with so few endorsement deals.

By the 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games in August, the IAAF had to make a decision: keep banning the world’s top runners for accepting prize money and demand that Olympic athletes not earn a living, or scratch the bans and ensure that world meets actually included the world’s best. Audain’s ban was lifted a week before the Games began and she was presented with her world record plaque for the 5000m inside the athlete’s village.

She won gold, representing New Zealand in the 3000m and leading from the very first step of the race. To this day, Audain remains the only New Zealand woman to win gold on the track at the Commonwealth Games. But that feat, while impressive on its own, is merely a footnote in a career that helped shape the very foundations of professionalism in sport around the world.

Audain continued to run for Nike in America after the Commonwealth Games and has the winningest record of any road runner in history. But as Nike grew, their focus shifted away from running, and so did their money. Runners today are still widely sponsored by Nike – watch the Olympics and almost everyone on the track will be wearing identical shoes – but the pay and celebrity Audain experienced in the sport now only exists in other codes. When Audain speaks in schools, she doesn’t talk much about Nike because she says it gives kids the wrong idea. “All the kids think I’m a multimillionaire, and I have to stand there and say, ‘No, no. The first generation didn’t get the money. It’s the Serena Williams, it’s all for the benefit of those girls.’”

Running as a glamorous sport may never return to the heights it reached in the 1980s with Audain at the top. But its athletes’ influence on the commercial success of toady’s most popular sports cannot be dismissed.

Before the 1992 Olympics where NBA superstars made their debut as the American Dream Team; before tennis and golf players could easily travel through America as professional athletes on working visas; before thousands of athletes got Nike endorsements; there was Anne Audain. Running, winning, and leading from the front, without hesitation.

Anne Audain features in episode two of Scratched, a new web series that finds and celebrates the lost sporting legends of Aotearoa. Watch her episode here, and episode one here.