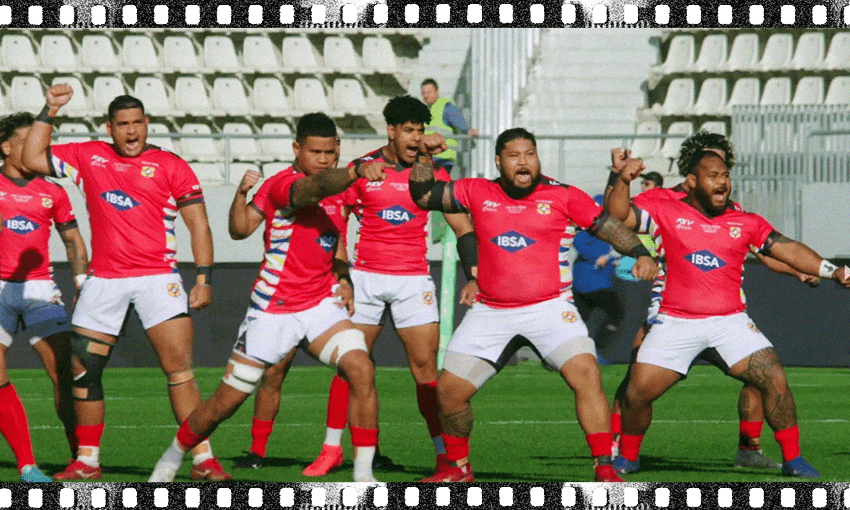

Kingdom of Kings takes you on a journey through the lives of Tongan rugby players – the sacrifices made, the challenges faced and the preparation leading up to the Rugby World Cup 2023.

In 2021, World Rugby announced that from January 2022, a professional player would be able to represent a different country after a stand-down period of three years, meaning a player could switch allegiance once to a nation of their, their parents’ or grandparents’ birth. The rule would apply to all players, but was noted particularly by Pacific players, many of whom play for larger nations like New Zealand, Australia and England rather than their smaller affiliated countries of Sāmoa, Fiji and Tonga.

The news excited director Sebastian Hurrell (Tongan, European descent) who during the time of the Pacific Nations Cup last year, was in Fiji filming a cooking show called Pacific Island Food Revolution. One night, Hurrell had kava with a few Fijian men who helped out with all the food aspects of the show. They chatted about the current results of the Pacific Nations Cup, which led to an enthusiastic talk about the new eligibility rule. “We finally get access to our best players like Charles Piutau, Israel Folau and Malakai Fekitoa,” Hurrell told them.

Hurrell shared with the men how, as a kid growing up in Tonga and then Aotearoa, when he would make up a Tongan dream team the best Tongan players would have already been selected for New Zealand, Australia, Japan or countries in Europe. Hurrell always wondered, “when are we ever going to get our own Tongan players playing for Ikale Tahi and not France?”

The new eligibility rule means during their professional careers, players would be able to play for two different countries. “We can finally attract our best Pacific players to come play for their homeland of Fiji, Sāmoa or Tonga and potentially have the strongest teams going into the next Rugby World Cup,” Hurrell said, looking forward towards the 2023 World Cup. While the three-year stand down period is a long time in professional rugby, the new rules mean a player like Israel Folau, who hasn’t played for the Wallabies since 2018, can now play for Tonga.

That very night, Hurrell had the idea to create a film about the Tongan rugby team Ikale Tahi (the name translates to Sea Eagles) – he says he’s always wanted to make films about Tonga, in Tonga. Hurrell wanted to share the stories of what it is like to grow up and live in the island nation. “The experiences Tongans go through such as poverty, lack of resources, living with humility, showing respect for their country and accepting that they live in a beautiful country,” Hurrell says. “Whilst we may have big dreams to go out and see the world, for most of us we accept what we have is all we’re going to have, and other people don’t really get that. It’s not something you’ll experience visiting Tonga and seeing it from the outside. You only get it by living it and those are the stories I want to tell.”

The production journey

Kingdom of Kings, Hurrell’s first feature film, is set to premiere in February 2024. It aims to highlight the issues of poverty, foreign politics, obesity and climate crisis through the lens of the Ikale Tahi team.

Hurrell got in touch with Ikale Tahi’s coach Toutai Kefu (a former World Cup-winning Wallaby) and the team’s chief executive officer Peter Harding with his story idea, with a request for him and his crew to follow Ikale Tahi during the lead up to the World Cup 2023 in France. They agreed.

Hurrell then spoke with his cousin and former All Black, Charles Riechelmann, about his film idea and if he would be available to join Hurrell to travel with the team and make the documentary. “Getting Charles on board was the best call ever because everyone in Ikale Tahi knew him and respected him. Toutai and Charles played against each other and so that opened all the doors for myself to then grab the interviews I needed for the film,” Hurrell says.

Hurrell, Riechelmann and director of photography Greg Parker flew to Bucharest at the end of last year – that’s where Tonga’s home games were taking place due to not having a rugby field ready in Tonga. “Tonga doesn’t have the right facilities such as training grounds, stadium, gymnasium to host matches due to financial hardship,” Hurrell explains. “They’re still recovering from a volcanic eruption, multiple cyclones and Covid-19, so it’s difficult for Tonga to get their resources to a top level.”

The story of Tonga rugby parallels Hurrell’s journey of creating this film working with a micro budget. The production thus far has been self-funded by Hurrell, with a Boosted campaign currently underway to help fund the remainder of trips needed to complete the film. The travel hasn’t been glamourous or comfortable either. “We were having to buy clothes in the countries we were visiting because we couldn’t pack any of our own as there was no room in our luggage. Our luggage was the camera gear,” he says. “We were stuffing our socks in small gaps inside our camera bags as we couldn’t afford extra luggage and we were staying in very terrible places.”

In the coming months, Hurrell and his film crew will be making two trips to Tonga. The first trip to the Kingdom is in July to film the parade to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the momentous occasion when Ikale Tahi beat Australia in Brisbane on June 30, 1973. “This is the only time Tonga has ever beaten Australia,” Hurrell says. This year also marks 100 years since the Tonga Rugby Football Union was formed in late 1923. The current squad is expected to arrive in Tonga in the first week of July to take part in the big celebration.

Hurrell will also be heading to Osaka, Japan to touch base with Tongan players who are residing there for rugby. “That’s really to contrast a country that has a lot of money versus Tonga’s situation,” Hurrell explains. “From a storytelling perspective, when you look at the dusty roads of Nuku’alofa to the big city lights of Osaka, it’s powerful imagery.”

In the documentary, a dramatic segment shows players’ interviews intercut with the ancient Tongan tale of No’oanga. It is said that Tongan men head out to sea, jump into the water and tempt the sharks with meat to come closer to their canoe, “Once the sharks swam closer, the men would quickly jump back into the canoe, trap the sharks and kill it with a mullet,” he says. “Tonga’s team manager Lano Fonua used this story in their first team meeting in France as motivation for the drive the players need to go and catch these big sharks or top rugby teams. It’s also an opportunity for us to insert Tongan language and culture into the film, so that it elevates the standard documentary into a true theatrical experience.”

‘We grew up playing rugby with a plastic bottle or a jandal’

The rugby players welcomed Hurrell and his small team into their homes for lunch or dinner to chat about their experiences and build a bond with each other before telling their stories in front of the camera. Hurrell wanted to capture the stories of the players earning big dollars and now having the opportunity to play for Tonga, but also the stories of the younger players coming up through the ranks. Another focus of story is the only Tongan player from Tonga selected for the squad, Sosefo Sakalia. Every other Tongan player is from a developed nation such as New Zealand.

“After Bucharest, we went to Tonga and spent time with Sosefo and his wife at their home as well as next to the grave of his late father,” Hurrell says. “Sosefo’s father was at his deathbed before the northern tour last year and he was a huge fan of Ikale Tahi. He told Sosefo, ‘you go and I don’t want you to come back. I want you to stay with the team.’ In the Tongan culture, losing your father is a massive ordeal, so to capture Sosefo retelling the story of getting his father’s blessing as well as give insight into the sacrifice it takes to be a part of the team was beautiful.”

Contrasting Sakalia’s story of being from Tonga are the experiences of Tongan players living in France, the UK, Japan, New Zealand and Australia. For these players, there are incredible benefits to playing overseas, including the opportunity to make good money for their families. But there are also sacrifices: many of the players talk of feeling homesick and the cultural shock of a new country. “I was talking to Leva Fifita in Ireland who is near his mid-30s, asking him how the body is holding up, especially playing against bigger, stronger and faster men,” recalls Hurrell. “And he just glanced out the window to his son playing outside and it all made sense. He’s willing to put his body on the line for his kids, so that they can have better opportunities in life.” Still, the adjustment can be tough. Hurrell has heard of some Tongan players in France who tried to grow their own taro, but the crops couldn’t survive the winters.

Wherever in the world that players are playing professionally, the dedication to the game and the purpose of why they play – for their family and their country – is the same. “All the players we talked to talked about growing up poor, whether in Tonga, New Zealand or Australia. The players talked about using a plastic bottle to play rugby with and having one meal a day. They talked about how their families worked hard to ensure they were able to have their rugby fees paid off or having a mentor that helped them with their sporting craft. This is why the players make the sacrifice to go play professionally in developed countries, so that they can give back to their families.”

More than just a rugby film

Although rugby is a huge component of the film, the story tackles a lot of other issues facing Tongans both within Tonga and abroad. Kingdom of Kings also addresses growing concerns like diabetes, the future of the next generation and the realities of living in a nation under threat from the climate crisis. One of Hurrell’s biggest worries for Tonga, and one of the main reasons why he wanted to make the film, is the possibility of Tonga falling short and not making the top 20 rugby teams in the world. At the last World Cup in 2019, Tonga finished fourth in their pool, beating only the United States. But now countries like the United States are investing more and more money into the game. “Georgia has a billionaire financing their rugby and now they’re ranked 11th. Japan is in the top 10 and have billions of dollars thrown at them, while Tonga, Fiji and Sāmoa are still languishing in the same spots. My fear is that teams with more money and larger populations will grow their national squad and push Ikale Tahi out of the top 20,” Hurrell says. Currently, Ikale Tahi is ranked at 15.

While they’re locked into this year’s World Cup, if Ikale Tahi falls out of the top 20 ladder in coming years, they will miss out on playing at the next one, which would mean the best Tongan players would miss out on the opportunity to wear the red rugby jersey on the biggest world stage. With 46% of the Tongan population under 20 years old, Hurrell asks the question: what will Tongan children look forward to if their flagship team is no longer playing at World Cup level? “Rugby is a massive part of Tongan people’s lives. The sport keeps them active and off the streets, making them do something fun in their lives. If Tonga is not playing at the World Cup and rugby disappears in Tonga, it will be a disaster for the next generation.”

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.