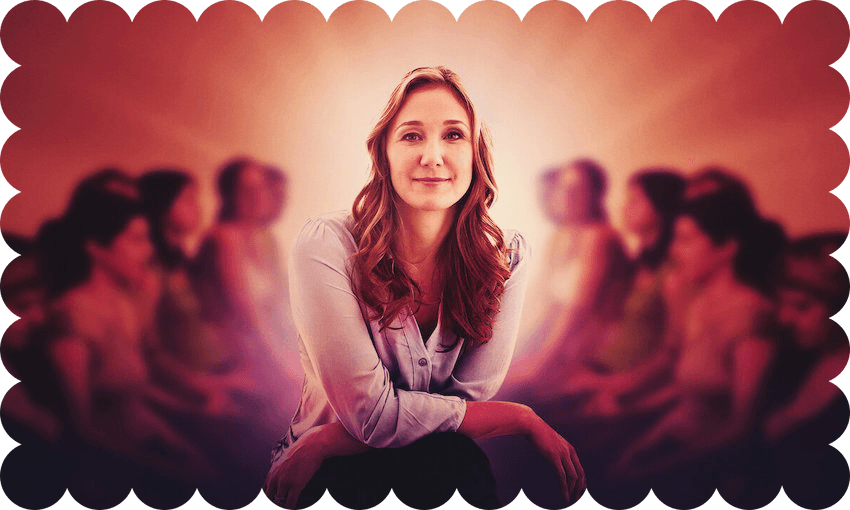

‘Orgasmic meditation’ was sold as female empowerment; meanwhile the business behind it was being investigated by the FBI. Cult Trip author Anke Richter recounts her own visit to OneTaste, the bizarre company at the centre of a new Netflix documentary.

First published November 12, 2022

My friend Lena*’s sex life was as unexciting as that of many long-married couples in their forties. But then things changed radically after she asked her husband to do something unusual with her. It wasn’t to visit to a swingers’ club nor to run through the 64 positions in the Kama Sutra. He didn’t even have to take his clothes off. She only asked for 15 minutes of concentrating on her most sensitive body part, with specific rules and a timer.

The practice they both learned from a video instruction was called OM, orgasmic meditation. A woman’s clitoris is stroked in a very precise manner while every sensation and visual observation gets communicated in an emotionally detached way between giver and receiver: “I feel a tingling in my left toe” or “the lips of your vulva are turning dark pink”. The aim is not to climax or to hook up, but to feel your own bliss and become a new woman: turned on.

The OM intro video was a product of OneTaste, a California-based company selling its horny feminism as empowerment for “turned on” women. Khloe Kardashian was into it and so was Gwyneth Paltrow and author Naomi Wolf. In fact, most of Silicon Valley seemed to be into it and able to pay the steep course fees, hooked in by the charisma of OneTaste founder Nicole Daedone. Her sales pitch was a merging of Buddhist mindfulness with sexual liberation, and it worked.

I visited OneTaste in 2017, a year before serious allegations about their manipulative and abusive tactics came to light, and five years before the release of the new Netflix documentary Orgasm Inc, about the rise and fall of Daedone and her company. At the time I was something of a semi-professional sex cult tourist, visiting Osho’s former ashram in India (later immortalised in another Netflix documentary, Wild Wild Country), completing an unnerving course with The New Tantra in Holland, and dabbling in the shamanic world of ISTA, the International School of Temple Arts which has a strong base in New Zealand. And I had spent years researching the aftermath of our homegrown disaster of a sex cult, Centrepoint.

Orgasmic meditation, or “OMing”, was spreading in the conscious sexuality and self-development scene. OM houses – communities where Daedone followers lived together – sprung up in major cities around the world. The one I was going to stay in for a German newspaper, undercover, was Forest Hill OM house in a leafy suburb of San Francisco. Their house rules, sent in advance, instructed me to pull the curtains before unpacking my bags and warned that I shouldn’t start conversations with the neighbours about what brought me there.

When I got out of the taxi, I found myself in front of a large and imposing villa. A young woman in sweatpants introduced herself as Sandra*, a resident of the house, and gave me a tour. The stucco ceilings were high, the wooden floors polished, the taps in the black-tiled bathroom golden, and the oversize fridge stocked with kale.

My room was as big as a ballroom and had a chandelier, but no privacy. Only a few shelves separated the bed from the common room which was empty apart from cushions and yoga mats in a corner. That was the space for the daily OM group exercise, known at OneTaste as “morning practice”. I wondered if I would be woken up by ecstatic sounds in the morning, but Sandra yawned and said: “We’ll sleep in tomorrow, it’s the weekend.”

She was sharing a double bed with a housemate on rotation. The sleeping arrangement wasn’t just because of the astronomical rents in San Francisco, but part of OneTaste’s philosophy: such closeness would tear your boundaries down and lead to more authenticity and intimacy. “All your shit comes up,” Sandra said. It sounded triumphant, almost aspirational. Still, I was relieved that my bed was going to be mine alone.

The OM introduction course the next day was in a warehouse in downtown San Francisco where we were welcomed in by a man with a wide smile and a t-shirt that said “Powered by Orgasm”. All the staff wore black, the women in high heels and cocktail dresses, oozing a sexy corporate vibe. This was a far cry from the neo-tantra hippie festivals I had frequented over the years.

The OneTaste members seemed highly focused, checking their laptops while chatting to each other like a crew of flight attendants before take-off. Our group of 40 was ready to fly. I had been worried that I would be surrounded by desperate old men but was pleasantly surprised: most people were attractive, with diverse looks; half of them were women. I didn’t know at the time that it was a ruse. In fact most paying attendees were indeed men – predominantly affluent tech guys who’d struck out with dating – and female OneTaste members, disguised as participants, were making up the numbers.

Natalie Thiel, then co-director of OneTaste San Francisco – she has a brief appearance in the Netflix documentary – was our instructor. “We all crave contact, we all have desire,” she explained. “When a man shows his sexual hunger, he is seen as predatory or repulsive. When a woman shows it, she is seen as slutty and desperate. So we hide our desires.” Many were nodding. I felt guilty about my earlier apprehension about being surrounded by sexually starved men. What I didn’t know at the time was that further down the track, long time OneTaste members would be allegedly encouraged to act out their libido in a sexually violating way. Both the documentary and a BBC podcast series on the same topic include allegations of rape. OneTaste has taken legal action against Netflix and the BBC while rebranding itself under a new name, Institute of Om.

Natalie began by writing ”orgasm 1.0“ and “orgasm 2.0” on the white board. The outdated model – orgasm 1.0 – was too focused on climax, an experience represented by a sharp upwards curve that suddenly dropped away. “Slow sex” on the other hand, as described by Daedone in her book of the same name, was the gateway to orgasm 2.0 and a new erotic paradigm: better communication, less shame and guilt, more authenticity and depth. What’s not to love?

All this, according to Daedone, we can apparently only access through a tiny spot on the female body, if we give it enough attention – the upper left quadrant of the clitoris, or the 1 o’clock position. It can’t get any more sensitive, Natalie told us: “This is where all the nerve endings come together.” To retrain the desire centre in our brain, we need to do daily orgasmic meditation, she said, calling it a “form of body hacking”. The way she described it, all perky and sparkling, she could have been peddling Tupperware to our group, if it wasn’t for the sprinkling of X-rated language like “pussy”.

During lunch, the hard sell started. Staff members around the table – all open, likeable, attractive – gave us heartfelt and well-rehearsed insights into how their lives had changed through OM and OneTaste. At the next table, they were already signing up newbies for further trainings, on trauma healing, empowerment and masculinity. Two weeks earlier, a OneTaste sales rep had called me from overseas, only hours after I had suggested interest via their website. She offered me a large discount if I paid by credit card on the spot.

Nicole Daedone’s name came up constantly on that day; the adoration for her was palpable. Millions watched her 2011 TED talk about ”the cure for hunger in the western woman” – an argument that better orgasms would satiate a widespread erotic craving that makes us eat, work, drink, diet and shop too much. Applicants for her week-long intensives paid over $US30,000 to be with her in person on the “The Land”, the organisation’s rural compound in Northern California. You couldn’t get more Nicole than that.

Before we were to experience the promised benefits of her miracle cure, we first had to learn how to find an OMing partner. We were encouraged to walk around the room asking others: “Would you like to OM?” The other person had to reply with an honest “yes” or “no”, no further explanation needed. It felt liberating to not take anything personally – their answer reflected only their preference, not a rejection of you. Everyone relaxed into asking for what they actually wanted, an exercise that is today a key part of many sexual self-development and consent workshops.

❓What is orgasmic meditation?

A woman lies on ‘a nest’ of pillows and ‘butterflies’ her legs (Daedone’s words), draping a leg over a fully-clothed man beside her.

⏰He sets a 15 minute timer.

Wearing latex gloves he then touches ‘the upper left quadrant’ of the clitoris pic.twitter.com/dnE1CcjJne

— The Telegraph (@Telegraph) April 23, 2021

Then the demo started. Natalie pulled down her skirt and her husband Paul came closer. She laid down in front of us, naked legs spread open. Paul put latex gloves on and rested her hands on her thighs to “ground” her. He dabbed lube – a special one that you could only buy from OneTaste – on his left index finger and started with a rhythmic stroke, gentle like the flutter of an eyelid. Natalie made sounds. Paul looked dreamy and concentrated, strumming her like a guitar, while she instructed him: “more to the left.” She moaned. He smiled. She came. Then he placed her hand on her vulva to ground her again. Fifteen minutes were up.

We were instructed not to clap but instead to express what we felt – without any emotion or fantasies, just a nonjudgmental observation of sensations in our own bodies. At the end of the day it was finally our time to practise, but with all our clothes on so that OneTaste wouldn’t be violating any prostitution laws. Even without skin contact, there was a feeling of intimacy between me and my practice partner (they called them “strokers”, I was a “strokee”). My stroker didn’t stick to the strict etiquette of robotic detachment and smiled at me after the session, saying: “I really enjoyed doing this with you!” A huge faux-pas. He would have a long way to go to qualify as a “master stroker”, which they offered courses for too. Female staff members were already circling and honing in on promising male candidates – a recruiting technique known as “flirty fishing” from other cults.

“We want the masses,” Natalie told me after we finished up. “OM should become as popular as yoga.” She claimed that at that time, over 14,000 people had taken the course we did or had downloaded the app. She sounded enthusiastic and unstoppable. “Are we your kind of people?” Paul inquired with a wide smile and piercing look when I said goodbye.

The next morning at the OM house, I gathered up all my courage. “Would you like to OM?” I asked house member Gordon*, as casually as checking if he wanted to play a round of ping-pong in the garden. He said yes. Earlier he had told me how much unpaid work he was doing at OneTaste over the years to follow his passion. He wasn’t my type at all and badly needed a haircut, but looks or attraction were irrelevant in this context – this was not a date, but an OM.

Gordon took me up to his room where he had prepared the “nest” on the floor, with a mat and cushions in the right position. The bed was taboo. Because nothing about it was romantic or flirty, taking off my pants and underwear in front of a stranger didn’t feel any more uncomfortable than at the doctor’s office. Gordon was equally clinical, our eye contact stayed neutral. “I’ll touch you now”, he announced, lowering his hand. I wanted more, then less, and I voiced it. “Thank you”, was his calm reply every time, like a human vibrator on remote control. Then the timer on his phone went off. “Two more minutes.” We gave each other precise feedback about what we had each felt in our body, and that was all we ever spoke. My life hadn’t suddenly changed.

That night, the house held a barbecue. No alcohol, no loud music, no orgies. All the guests talked about the courses they had been on or were saving up for next. Sandra told me she gave massages after work to be able to afford a “Nicole Circle”, a women-only weekend with the leader that would set her back US$6500. Only gaunt and grey-haired Mark*, who had known Daedone since her wild days at the sex commune Lafayette Morehouse and followed her loyally on her unusual career path ever since, seemed weary. He became a sex addict in the early days, he told me. Now he was monogamous. OMing for him was “like walking the dog – you don’t always feel like doing it, but you know it needs to be done.”

Because I was flying out the next day, I missed the midday group OM. Despite my curiosity about OneTaste, it was a relief to be leaving. Even as a visitor, I felt subtle pressure to conform, to pick up the OneTaste language, to act like I was on board with it all and hungry for more. At San Francisco airport I passed the yoga room. Natalie Thiel and her team had told me that they were dreaming of their own OM room for travellers there. It sounded ambitious at the time, if not utopian. But since then, their utopia imploded.

What I experienced that weekend is now only taught online; OneTaste in San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York has shut down. In 2018 Bloomberg published an exposé revealing how the clit corporation was pushing students into expensive trainings, isolated them from their families, making them emotionally dependent and pressuring them into sex. In the following years Netflix and the BBC introduced the organisation’s controversial practices to a wider audience. While some sex therapists had praised OMing as a tool for more body awareness and better sexual expression, it had become the gateway drug for exploitative self-optimiszation – a trap. The sex cult had turned into an alleged sex trafficking cult.

But my friend Lena still swore by her orgasmic meditations – with the woman she now loves. After she realized her true desires through her daily OMing, she left her husband and had her coming out. Lena even thought of flying to the US to take a OneTaste course to go deeper, but the price tag stopped her in the end. I’m glad about both.

Anke Richter’s new book Cult Trip: Inside the world of coercion & control (HarperCollins) is out now. She will speak at Splore Festival on February 25.

*some names have been changed