As her family home goes on the market, Lucy Black reflects on a childhood full of books, libraries and reading.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

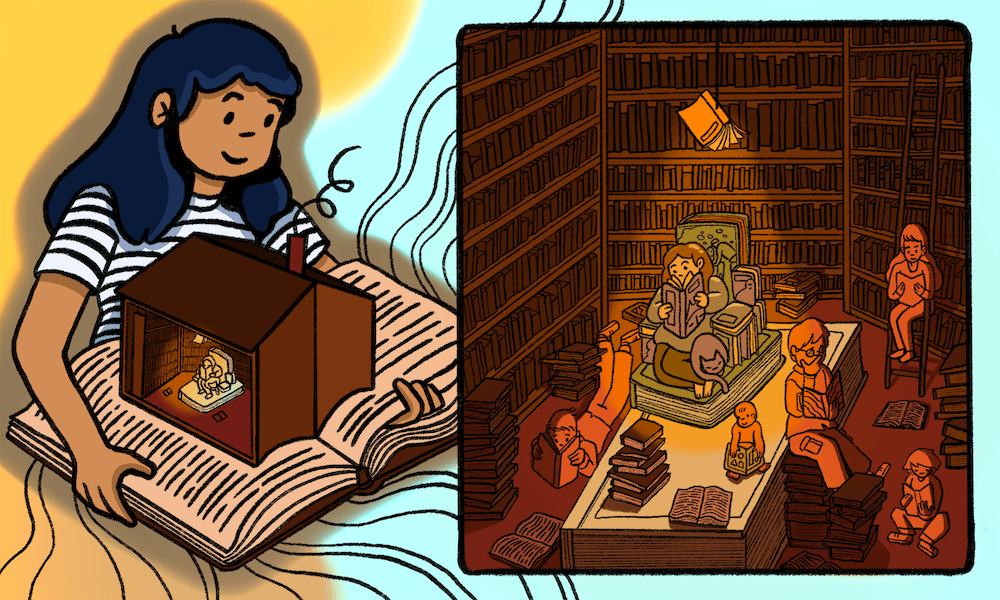

Illustrations by MK Templer.

I am the last of four children and when I was growing up we lived in a small house that was full to bursting with the stuff of six people: rackets and boardgames, sheepskins and roller skates, Playmobil and camping gear, and spare clothes for the kids we fostered, and photos and records, and straw dolls and tools. So much life detritus. A large part of that small house, and what I think about when I think of those days in the 80s and 90s, was books: ever present and looming around us on tall, home-built shelves.

My parents weren’t literature professors or publishers; my dad was a civil servant and Mum worked at home and then part-time as a teacher’s aide. But for whichever reason, books and reading were very important to them. Perhaps it was that they had both worked at the national library briefly as students? Or that when they were newlyweds they would lie in bed and read Russian classics aloud to each other? They never had much money, and we didn’t have any fancy things. Mum bought all our clothes second-hand and knitted us jerseys and we often had classic feed-a-large-family meals of mince, casserole or baked beans. But they had books. I don’t remember shopping for them: I guess they came from opshops and school galas. They were hardly ever brand new but books were always there.

The coffee table in the lounge had stacks of picture books and old Listener magazines. I remember John Birmingham, Helen Oxenbury and Raymond Briggs, and begging to read the same Maurice Sendak and Mercer Mayer books over and over again. I particularly treasured my Miffy books and liked to line them up in their crisp and simple squares. Next to Dad’s bed was a big shelf of his books: Kahlil Gibran, mystics, maths textbooks and poetry.

Mirroring that on Mum’s side were hers: historical novels, Agatha Christie and pretty books about the language of flowers. Both the small kids’ bedrooms were filled with picture books and chapter books and those terrible craft books from the 70s which involved using things we never had, like hot glue and coffee filters. I remember sitting on the brown carpet in front of my big brother’s shelf in terrified silence as I read The Usborne Book of Ghosts, then hiding it behind a large first communion bible because its spooky radiance was too powerful.

The result of all of this was that we all read a lot. I was also read to, often. I taught myself to read by pouring over the Arthur Rackham illustrations of my nursery rhymes and the Ladybird easy-to-reads. I would diligently bring readers home from school and sound out a story from the Junior Journal while Mum ironed and watched Sale of the Century. I don’t remember reading being an option or up for discussion; I assumed everyone did it. I couldn’t wait to chew through the pages the way my family did. Dad would have a book in his briefcase that he read on the train, and on a sunny afternoon when Mum wanted him to be doing the lawns, he was more likely basking in the sun with a fat novel.

Mum read at night when she was alone. If I woke from a nightmare and went to the lounge she would be on the couch, her beautiful long legs stretched out with a glass of sherry, chocolates and a library book. My siblings read fast, gulping the words as they gulped their milky Weetbix, passing fantasy novels among themselves and talking about characters with unpronounceable names. I didn’t choose to be a reader – we were Catholic, we were lefty, we were working class and we were readers.

Each night after the dishes and before bed, Dad would read a bedtime story. He must have been tired from his day at work, the commute on the train, the walk around the bays. He probably wanted to sit in his chair and watch TV, but instead he read to us every night. I would lie next to him in silence as he read chapter after chapter, and then just one more. He read me The Chronicles of Narnia and I learned of my namesake, Lucy. He read to me of brave children unlike myself, who led adventuresome lives, like Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons and the Melendy children in Elizabeth Enright’s books. When I got a little older, he read to me about Ged and The Tales of Earthsea, and Susan Cooper’s wild magic stories of siblings lost in folklore. The fading, psychedelic, vintage covers entranced me and each book felt like a hand me down treasure that my siblings had poured over and I was finally allowed a hoon on.

As a kid, I assumed in the egocentric way of small children that my dad really wanted to hang out with me every single Saturday morning. Now I am a parent, I realise my mum was probably desperate for some free time at home and ordered us out of the house. Dad dutifully took me to the Porirua public library, and in my mind that was library morning in the same way Sunday was church morning. I adored the library. I even have scars to prove it: one time, aged four, my book stack was overly ambitious and I fell down the library stairs, cracking my forehead right open.

I loved the hours alone at the library where I wandered the shelves and had the autonomy to pick whatever I wanted. Dad never encroached on my choices or censored what I read. I think, like the Nescafe instant coffee I drank at home, I probably started on the YA and adult collections ‘too early’, but what a thrill. I greedily consumed books by Lois Lowry, Louise Fitzhugh, M. E Kerr, Paul Zindell, Cynthia Voigt, Robert C. O’Brien, Katherine Paterson, Francesca Lia Block, John Marsden and Paula Danziger. All those familiar, scuffed paperbacks with angsty girls on the front, staring forlornly at the reader. I learned a lot about my place in the world, relationships, families, my sexuality, religion and ethics from those pulpy but thoughtful writers.

Dad would take me to the cafe for a neenish tart or a lamington and a small bottle of Chi (the drink that knows its own name), and then we would go home for long afternoons of reading. I wasn’t cool and I wasn’t invited anywhere or part of any groups. Sometimes I hung out at the jetty or the skate park, but mostly I remember being at home and being alone, with the dust motes floating in the sunbeams, milky coffee, my book and my cat.

Reading was so much a part of my daily life that I didn’t think it was in any way extraordinary. I wouldn’t have listed it as a hobby because that would be like listing ‘drinking water’ or ‘sitting down’ as hobbies (I do love to sit down). But because I didn’t see my reading habits as a skill or a pursuit, I might have missed some opportunities. I didn’t realise that studying Literature with a capital L was basically just reading and I didn’t realise that being an Author can be pretty easy if you were a reader. I lacked confidence and I didn’t see my cosy security blanket of books as resources or anything more than pleasant ways to pass time.

As an adult, I began to slowly realise that not everyone had been surrounded in an insulating layer of reading material. Not every family shared common stories and had cultural touchstones in the same way mine did. I continued to read and so did my family. Each visit back home involved reading recommendations, book gifts and discussions about which TV and film adaptations had been done badly. My first full-time job was at a public library, and when I had my first child a huge part of my preparation was filling my home with kid’s books. I remember when the Plunket nurse weighed my tiny pink baby like a parcel of ham in a cloth nappy, she asked if I was a professional book collector. I wish that was a profession.

My family of origin is not perfect, not wealthy or mentally healthy, but I’m thankful we share this love of reading. My mum died in 2014 and my dad is ill. The run-down old home that we grew up in is for sale. After over 50 years in that house, Dad has to move. A few weeks ago, I went with him to look around the strange and smelly retirement options the Kāpiti Coast has to offer. We looked at man-made lakes and frozen meal options, asked about emergency call buttons and strained for glimpses of the island.

Dad talked to the sales agents about his yearning for tree-filled gardens and contemplative quiet that he can’t afford. I determinedly gritted my teeth and sought out the leisure centre libraries. It’s been hard for Dad, making compromises, changes and sacrifices at this time in his life, but he’s still very sharp. None of the libraries stood up to our scrutiny.

Dad is down to one large bookshelf now. My brother and I sorted through the collection, saving some books for our shelves and donating others. I came home with my stack and I was thrilled to see my parents’ names carefully penned into the front covers. I flipped through the pages hoping maybe I’d find a lost note or even a photograph. I squeezed the new arrivals into my already pretty full shelves and promised myself I’d read more of the books I own and cut down on the library reserves and new book purchases (I will break this promise).

When I had finished gazing fondly at my shelves, I went into my kids’ rooms to say goodnight. My eight-year-old was tuckered out, already drifting to sleep listening to The Last Fallen Star by Graci Kim. It was school holidays and my 12-year-old was sitting up late, in a pool of lamplight. The cat had snuck in and they were a picture of contentment. I told them it was lights out in 10 minutes. I didn’t enforce it.