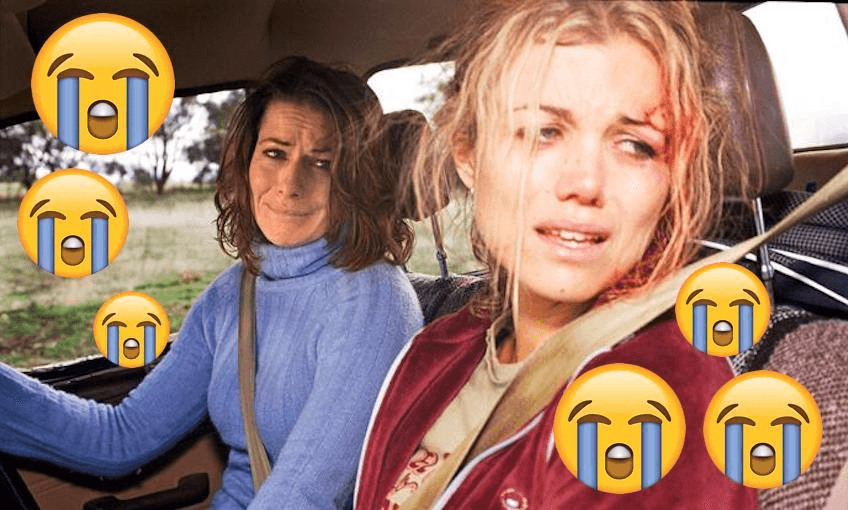

Claire from McLeod’s Daughters died in 2003 and Tara Ward is still not over it.

The unexpected death of Claire McLeod is the most tragic event you’ll see on television. It was a miserable day when that white Brumby bolted across the road and made Claire drive off a cliff, leaving viewers a traumatised wreck. Surely the entire equine race has to take some responsibility for TV’s most emotional demise, and yet, when horses are confronted with the truth, what do we get out of them? Absolutely nothing.

Look, it could be the grief talking. Ghost Claire said her death wasn’t the horse’s fault and Harry Ryan reckoned it was a terrible accident, but the same Harry Ryan once spent an entire episode trying to climb some stairs without puffing, just to prove he was fit enough to have sex with his wife. Jog on Harry, so I can keep pointing my clammy finger of blame at the horsey harbinger of doom who made a gaping wound in my soul, one that still festers like a mangey ewe nearly twenty years later.

Claire McLeod was the beating heart of McLeod’s Daughters. Gutsy single mum Claire and her city-slicker sister Tess ran Drovers Run, the Australian farm filled with a thousand broken fences and as many ruined romances. Claire loved the land as much as she loved high-waisted jeans, and she and Tess turned Drovers into a feminist utopia where women could do anything. Tess was nice enough, but Claire was the better sister. She once made Tess walk a bloated cow round the garden all night, just so it could do a massive fart. Claire was a hero.

Claire had never been happier than on the day she died. After three seasons of farmyard sexual tension with Alex Ryan, the Darcy to Claire’s Elizabeth, the two lovers finally hooked up. Alex owned as many flannel shirts as Claire did, and moving in together meant they could talk endlessly about dags and drench. After Alex put his junk in Claire’s cellar and Tess got the cancer all-clear, Claire wanted to celebrate. She was going to Gungellan to get some corn chips.

Dip your ghost corn chips in a jar of my salty tears, Claire McLeod, because rewatching these scenes in 2020 feels as visceral as the first time around. The moment that Brumby bolts across the road still makes my heart pound in an unhealthy way. It’s the beginning of the end, and 17 years on, I am still not ready to say goodbye.

First, there’s the wild chaos as Claire hits a pothole, drives into a tree and through a fence. Science suggests the pothole was about one centimetre deep, but now is not the time for questions, Your Honour. Save your hesitations for seasons five through eight, when McLeods becomes consumed by secret cousins and witness protection storylines that will make you will curse the day Claire ever drove over that tiny bump.

There are screams as the out-of-control ute hurtles towards the death trap of a canyon, and then, silence. The front of the ute dangles over the cliff edge, as the two sisters realise this situation is way worse than the time Meg’s prize-winning chutney went all wonky and nobody could work out why.

Claire knows she’s in trouble. Her knee is wedged under the steering column and her door won’t open. The ute lurches forward each time she blinks. Channelling the courage of that farty cow, Claire tells Tess to get out and save baby Charlotte. Tess makes excellent coffee and probably championed avocado on toast years before its time, and she’ll use a rope to secure the ute to a tree. It’s fine, everything’s fine, it’s all fine.

The rope is too short. That’s not good.

McLeod’s was a show about women who got shit done, but this moment carries the awful realisation that there’s nothing more the sisters can do. Claire says a final farewell to Tess, but she’s saying goodbye to us too. In 2020, the ghost of Claire McLeod will turn up in Ferndale to pash the hell out of Chris Warner, but in 2003, as the cliff begins to give way with Claire still trapped inside the ute, this is the end.

Claire is a hero, one last time. “Look after Charlotte,” she tells Tess, pushing her little sister to safety. The ute slides over the side. Claire McLeod is gone.

Welcome to the sound of your heart breaking into a thousand Claire McLeod-shaped pieces. It’s even worse when you watch the ute fall, because the crew dressed a mannequin in a blue jumper and brown wig and taped its hands to the steering wheel. It’s possibly the grimmest moment of all, the final nail in the fictional coffin. We’re bawling our eyes out, and Claire McLeod wasn’t even real. She’s just a dummy in a canyon. We are all sorry now.

Whoever the dummy is here, no other television death hits you with the same raw, gut-wrenching impact of Claire McLeod’s. Not Daphne croaking “Clarkey” on Neighbours, or Shortland Street’s beloved Sarah Potts, or Patrick on Offspring. Claire never came back from Gungellan, and McLeod’s Daughters never got over losing Claire. Give me another 17 years, and I might be ready to consider it.

Related: