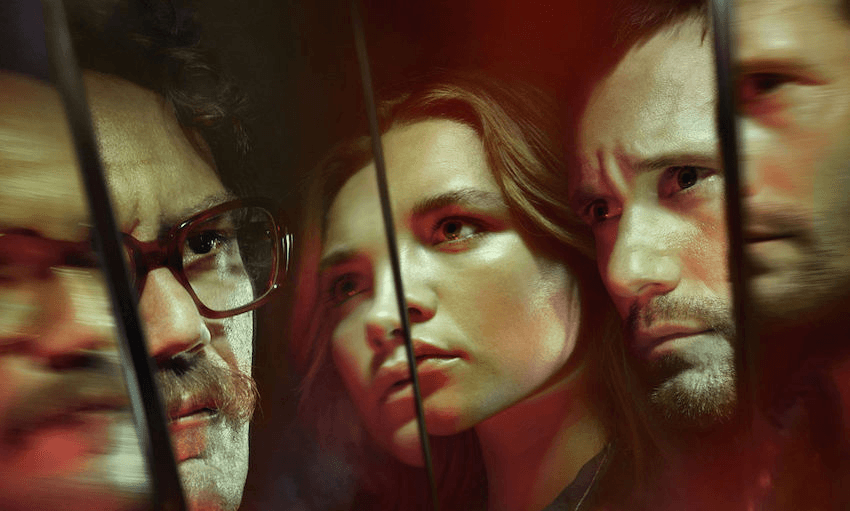

What do you get when you mix a South Korean auteur, a French-sounding British spy author and a ridiculous attractive cast? A genuine must-see. Sam Brooks reviews The Little Drummer Girl.

When I think of John le Carre, I don’t think sexy spy drama. If anything, the man has done whatever he can to dispel the myth of the sexy spy. His novels, most famously The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, are the antithesis of James Bond. There’s no death-defying stunts, there’s documents. There’s no torrid love affairs, there’s simple seductions and mistakes poorly made. Le Carre gives us the desaturated reality of people in the intelligence business – deeply damaged people who happen to have a skillset and skewed moral compass that lends themselves well to keeping secrets.

On the other end of the spectrum, when I think of Park Chan-Wook, I don’t think of sexy spy drama either. I think of wild tonal swings to the wall and an audacity in every aspect of visual and aural design that overwhelms, and even supersedes the need for narrative logic or reason. In my favourite of these films, the vampire melodrama Thirst, he swings so wildly for the walls he breaks the foundation of the genre. Spy dramas, which tend to be intricately plotted and delicately nuanced, don’t seem to match up with his aesthetic.

So when I was told that Park Chan-Wook was helming the miniseries adaptation of John le Carre’s The Little Drummer Girl, I paused and went, “Huh.” There’s a long list of visionary directors whose visions and sense of style have been swallowed by television and digested into something smaller, something neater. Todd Haynes, Martin Scorsese, Dee Rees, Lisa Cholodenko. They’re not necessarily lesser than any of their filmic achievements, but more often than not they feel like the homeopathic version of the director’s work. Even Susanne Bier, the director of le Carre’s previous television adaptation, The Night Manager, comes from a place of melodrama that doesn’t necessarily feel like a great fit for le Carre’s work.

Similarly, television can do terrible things to an author’s work. What is tense and thrilling on the page can end up tepid if treated with reverence, or merely treated as faded old blueprint. John le Carre’s writing is not exempt from this, and for every slam-dunk adaptation like the 2010 Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, there’s a dud that now exists only as a footnote on some executive producer’s old budgets, like the 1984 version of The Little Drummer Girl, a flailing Diane Keaton limp wrist of a film.

Despite my trepidations, The Little Drummer Girl is a runaway success of an adaptation. Rather than being a clash, the surgicial precision of le Carre and the impressionistic brushes of Chan-Wook complement and enhance each other. I can’t remember the last time a show set in the modern day had a striking, iconic outfit – and Chan-Wook gives us three in the first two episodes alone, along with some of his classically primary-coloured production design. In saying that, there’s no small amount of work done by the cast to make the oft-remote le Carre feel present, and to stitch the oft-coherent Chan-Wook together into the gorgeous tapestry that this mini-series is fast turning out to be.

This is not easy stuff, given the heady concept of The Little Drummer Girl. Set in the politically volatile time of the 70s, especially if you were anywhere near Israel and the Israel-Palestine debate, the mini-series revolves around three key players. The first of these is Martin Kurtz (Michael Shannon, who continues a solid run of never disappearing into a role ever), an Israeli spy whose entire job revolves around making sure that his superiors have plausible deniability. The second is Gadi Becker (Alexander Skarsgård working a difficult accent like an ill-fitting tuxedo), who appears to be a tall and dark stranger, because he is played by a young Skarsgård, but is actually a foreboding and quite terrifying spy, because he is played by any Skarsgård at all.

The third, and most important, player in the show is Charmian ‘Charlie’ Ross, played by Florence Pugh. While Shannon and Skarsgård are probably familiar faces to anybody who has watched their share of critically liked film or television, Pugh is a newcomer (unless you happen to be a fan of tiny British indies, in which case you would’ve seen her tremendous performance in Lady Macbeth) and she pulls the rug out from under the feet of both her other performers and the audience on a shockingly consistent basis. It’s a tricky balancing act to let an audience know exactly who you are in the first moment you walk onscreen – in this case, an actress who is probably the smartest person in ever after-party she’s ever attended – but also keep them guessing, and Pugh handles both with the ease of an experienced pro.

Charlie is a headstrong, intelligent actor who is led down the tricky path of ill-advised political statements and parties until she falls across Becker’s path and is quickly recruited (kidnapped) for a cause she barely believes in. Ostensibly, this is for her skills as an actress. Quickly, it becomes clear that it’s more for her skills as a human being capable of deceit – so any human being, really.

In Le Carre fashion, the plot rolls out slowly. It’s only by the end of the second episode that we have any sense of what Charlie is being asked to do, but through both the precision of the writing and Chan-Wook’s sly amping up of the stakes with stylistic flourishes (characters look straight into the camera, conversations being filmed entirely through aerial shots, and quick, cutting inserts), the audience is kept on the balls of their feet. At any point, someone’s true motives could be revealed, or a vaguely hinted at piece of information could become a concrete fact.

Pugh seems like the perfect meeting point for the aforementioned sensibilities of Le Carre and Chan-Wook. She nails the process of a human subsuming and suppressing her humanity in order to do a job, albeit a job she’s been coerced into with striking clarity, but she also shows Charlie’s vivacity in such a way that reminds us that despite all this spycraft and politics (although as Kurtz says, “We’re not talking politics, we’re talking beliefs”), that there’s still a human being under there. As an actress fending off boorish men and even more boring activists, her wit was her weapon, but in a world where people are plotting and counter-plotting, her wit is her armour.

The first episode is mostly set-up – all foreplay, no sex (in a literal sense) – but the second episode rolls out in a delightful fashion. Charlie’s interrogation by Kurtz is a slam-dunk of a scene, 20 minutes, of back and forth and the slow breaking down of Charlie by the revelation of every small misdeed she’s made in the last few weeks, family history she’d rather keep private, and a gradual push of each wall in on her.

The heat turns up even more when Charlie is convinced (read: coerced, threatened) into working for Kurtz and with Gadi, posing as his wife. There’s a genuine attraction to him, because he’s played by Alexander Skarsgård, and the scenes between him and Pugh are full of that tentative heat between people who are attracted to each other but know there’s something else they should focus on. A scene between the two where they explain what would have happened if they had had sex is sexier than anything on HBO – it’s all loaded comments, husky voices, and quick repartee. With actors this skilled, and frankly, this attractive, it’s the closest that le Carre has ever come to being Coward, and it’s a welcome departure from documents and dossiers.

Because Le Carre’s stories are never really about spies or politics; they’re about people. They’re about the capacity of humans to bend – to lie, to manipulate, to self-delude – and just how much a human can bend before they break or somebody breaks them. And, having seen two episodes out of six, I can’t think of a better director to attach to this material than Park Chan-Wook – a director whose surfaces are so clearly surface that we can’t help but investigate the levels of performance that don’t just build up each person, but the very world that surrounds them.

It also wouldn’t be Chan-Wook without those surfaces and flourishes – like the chilling image of a group of intelligence analysts chowing down on ice blocks while the screams of someone being tortured are heard in the background – and they’re a big part of what makes this show stand apart from not just every other Le Carre adaptation but other spy dramas. What they hide in the subtext, Chan-Wook makes beautiful, caps-lock TEXT.

Nowhere is this more clear that when Gadi says to Charlie at the end of the second episode, in the moment where her illusion of a faked love becoming real, a mission being easy, someone’s beliefs being put to the side, shatters entirely and is replaced by a genuine, palpable threat to her life:

“This is your debut in the theatre of the real.”

It is bloody ever.

You can watch The Little Drummer Girl on TVNZ on Demand. Episodes One and Two have screened, and will roll out every Monday.