The best little art show about the environment is big on charm and low on preaching and you can find it at Robert Heald Gallery in Wellington for one more week. Megan Dunn reviews.

Are we all screwed? Pastorale, the current show at Robert Heald Gallery in Wellington, suggests not yet, but we might be soon.

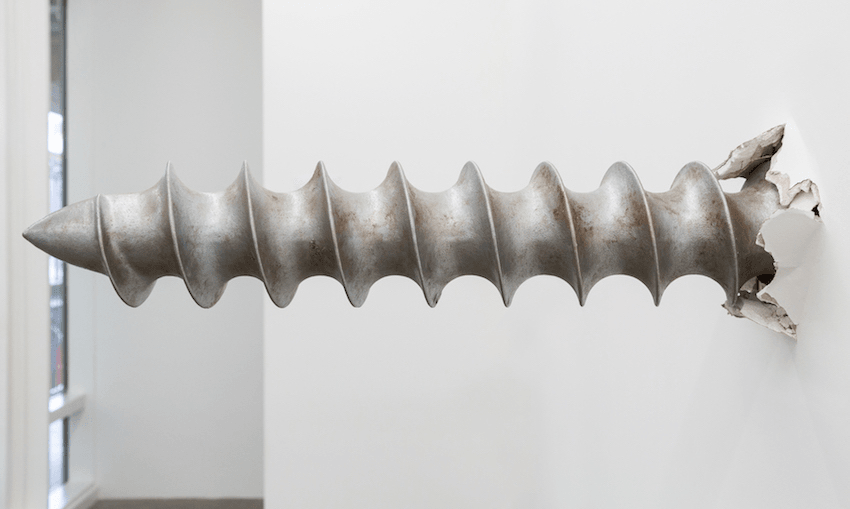

Six massive rusted drill bits appear to have broken through the white walls as though the gallery is under attack from supersized builders. The drill bits are sculptures by artist Joshua Petherick made from patinated polyurethane foam. Petherick has titled this series ‘Condolences.’ His drill bits look convincing too. As a metaphor, Petherick’s ‘Condolences’ seem to imply that the world is being penetrated and rebuilt by giant forces you can barely understand.

“It’s my environmental show,” Heald joked the day I visited the gallery.

Yes. No pastorale moment can go without interruption from our gnawing awareness of potential environmental calamity. At this point what can we offer other than our condolences? Alongside our commitment to go vegan, quit air travel and eliminate all plastic consumption.

But first, a brief introduction to Robert Heald who is easily running the best dealer gallery in Wellington right now. In early 2019, Heald’s gallery relocated premises and expanded into two large conjoined spaces, upstairs in the Left Bank precinct off Cuba Street. Over the past decade, Heald has built an impressive roster of local artists but also interjects a small cast of eclectic international names into the mix. So, in the main gallery space Petherick’s drill bits are paired with the Italian artist Piero Gilardi’s nature studies, also made from polyurethane foam. Five white plinths present each Gilardi nature study like bisected slices of earth, in colours as vivid as marzipan cake decorations.

Gilardi was first associated with the Arte Povera movement and is best known for his ‘nature carpets’ from the 1960s. His nature carpets are just that: rolls of stones, grassy gardens, banana groves and seascapes made from rubber foam – viewers could walk all over them. “I had an idea about these carpets one afternoon when chatting with a friend about the landscape that will surround man in the future,” Gilardi once said. “Somewhat excited, I imagined a naturalistic environment that was artificially made from synthetic materials for reasons of comfort and hygiene.”

My response: Um, yes but no. Gilardi’s soft sculptures now look as camp as Christmas. In Zucche e prugne (2018) a verdant pumpkin has one slice excavated from its side; its seeds scattered across the scene. It looks like an Anne Geddes set-piece, minus the baby. (In the gallery backroom I leaf through a Gilardi book and discover some 60s vixen coiled in a watermelon costume made of foam. Seedy.) Nature is increasingly unreal – the site of our corruption, our calendars, our best efforts to save the world and our terminal sentimentality.

Now for a reference from The Muppets. “There’s something happening here, but what it is ain’t exactly clear…” The intersection of Petherick’s condolences and Gilardi’s nature studies also reminded me of a classic clip from The Muppets in which an opossum and a cute cast of woodland animals sing Buffalo Springfield’s hit, “For What’ it’s Worth.” Pastorale suggests a narrative the woodland animals might like to sing along to as well. But what’s the moral at stake? I loomed over Bosco in riva al mare or The Scents of the Forest by the Sea (2017), a wistful foreshore of pebbled stones that looked as though the miniature wave in the corner was rushing in. The scale turned me into a giant like David Attenborough or perhaps just Jim Henson, wondering where to put that next opossum. “Stop children, what’s that sound, everyone look what’s going down.”

In the adjacent gallery, Dunedin-based artist John Ward Knox – the son of musician Chris Knox – presents Estuary Madness. Two wooden sculptures called kēkē – Māori for ‘to quack’ – have elongated necks that sinew and snake. Each is installed on either end of a zig-zagged wooden plinth. Ward Knox salvaged this plinth and many of his materials from the estuary near where he lives. The anthropomorphic kēkē are bewitching – but also retiring a bit like sculptures made in an old people’s home.

Whereas Pastorale gains its oomph from those big nasty drill bits, Ward Knox, always the master of understatement, presents a series of drawings that are teeny tiny. His Deviations are drawn in pencil – and each is of a hand performing some crafty fine-motor activity, maybe in the process of carving the agile kēkē. The Deviations are presented on the back of throwaway receipts including a Lotto ticket, a Keno draw, a Next receipt, each electronic print out has been turned to the wall, held in place by a twist of wire. The Deviations snatch some mystery back from loose change and suggest that resistance to capitalism might start small. From human nature something wild and beautifully wrought might just be salvaged – we still have a chance to foot the bill. Or has estuary madness warped my mind?

The moral of this art review? There’s no escape from climate change in art right now. In Auckland at the Gus Fisher Gallery, The Slipping Away is a group show partly about the saturation of plastics in our oceans. At the current Venice Biennale, the award for best pavilion went to Lithuania for Sun & Sea (Marina), a live opera of beachgoers singing about the velocity of climate change. In the New Zealand pavilion, Dane Mitchell’s Post hoc installation includes a dramatic cascade of lists of everything vanished from the world. For the seven months of the biennale, Mitchell’s lists spill from a printer like an endless waterfall.

What can we do about it? Send in a chorus of muppets.

Pastorale and Estuary Madness are at Robert Heald Gallery in Left Bank, Wellington until Saturday 17th August, 2019.