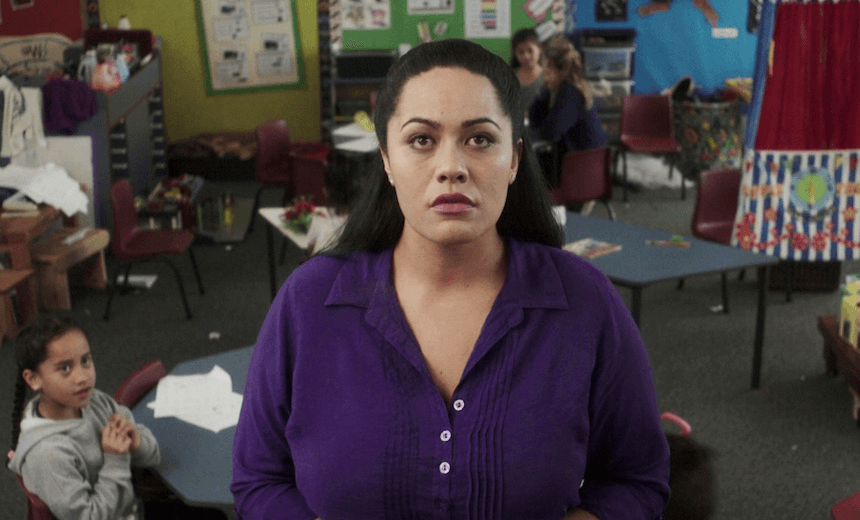

Filmmaker Kath Akuhata-Brown looks at the unique challenges of making Waru, a film directed by eight Māori women.

Beneath the yelling and screaming of our recent general election, as child poverty was being turned into a political platform, a group of Māori filmmakers quietly went about the task of drawing attention to the issue in a real, meaningful way. The result was Waru, a portmanteau film comprised of eight stories about and by Māori women making a stand against child abuse in their own communities.

The film featured at the New Zealand International Film Festival this year, won rave reviews at the Toronto International Film Festival and is due for general release here in Aotearoa on October 19th.

The brief for the film was a difficult one: A child dies at the hands of a caregiver and during the tangihanga the wider whānau implodes.

Each filmmaker was given a set of non-negotiable parameters – they had to have a female Māori lead, the story had to connect to the death of a child, all the stories had to take place within the same 10-minute timeframe, and the vignette would be one continuous shot.

The genesis of Waru started with producers Kerry Warkia and Kiel McNaughton of Brown Sugar Apple Grunt Productions in 2009. They sat on it for a while and then in early 2015 they wrote and pitched the project to Te Māngai Paho, then NZ On Air and the NZ Film Commission. Once they confirmed funding they put out the call for wāhine Māori writers/directors in late 2015 and had over 40 women apply.

Writer and director Renae Maihi (Ngāti Whakaeke, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whakaue, Te Arawa) says one of the thematic questions posed within the film is: “If it takes a village to raise a child, does it then take a village to destroy a child?”

“We are the villagers in the village which has been separated or forced apart. We need to come back together, keep an eye out for the welfare of our descendants and be courageous to speak up if there is a problem. There is no mana in turning a blind eye. Another core discovery is the harm that addiction plays amongst our communities. Alcohol and drugs are destroying our people,” she says.

A few years ago she wrote and directed Patua, a play about family violence, and has been interested in those difficult themes since.

“I saw this as another opportunity to give voice to our lost children and encourage New Zealand to examine ourselves and the part we have to play in these tragedies,” she says.

Standing ovation at the #BigScreen16 for the WARU wāhine. Photo by Casey Kaa. #WaruFilm @BigScreenSNZ #ManaWāhine ???????? pic.twitter.com/JUAVO6QQZo

— Kerry Warkia (@KerryWarkia) September 25, 2016

Having a television and filmmaking background, I was sent the brief as part of the search for writer/directors. In my mind too many negative stories had already been written about Māori and I could not reconcile with being yet another writer to tell a story about how useless my people are. I walked away from that when I left commercial television in search of ways to discuss the many problems of our people while honouring the good things.

I should have realised that when a group of intelligent Māori women get together and are given the reigns, there is only room for a story grounded in aroha and tikanga.

Ainsley Gardiner (Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Pīkiao, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui) speaks directly to this dilemma.

“I was reluctant to be involved at first, I felt aggrieved that we were bringing these amazing wāhine Māori filmmakers together and a story of abuse was the one we were going to tell.

“I told myself to do it to develop my directing skills and I liked the idea of working within constraints that were not my making. Within a couple of hours together with the other writers and directors I realised how wrong I was about the story and why it was very much the right story for us to be making. The fact that when we spoke as Māori, as mothers, we had so much shared experience and that despite our varied backgrounds, we had all experienced struggle in our lives or in those of our families. It was the realisation that collectively we had something to say that might speak to others truly.”

These proud, courageous wāhine filmmakers could see what I couldn’t. One of the roles of the writer is to reflect not deflect and so they went about producing one of the most important films to come out of this country. As a viewer I loved this film. As a filmmaker, I was damn proud of my friends and peers. All of them are working toward directing their own feature films.

Playwright and writer of the film Strength of Water, Briar Grace-Smith (Ngāti Hau, Ngāpuhi, Whakapara) says she welcomed the opportunity to exercise her directing muscles.

“I enjoyed the challenge of writing a film in one shot and exploring the moments and characters that were linked. On top of that I decided to write for a really big cast. So the writer in me had a lot of fun, but on rehearsal day when I walked into the room and saw all of those actors and the physical reality of what I had written, the emerging director in me wanted to die.

“However I was working with several theatre actors and all that training around use of space came in handy. We blocked the scene several times (but were careful not to over do it) during rehearsal. Actors also had cues and they knew when to come into the scene and when to leave, where to put their feet and where to drop pavlovas… it was a small space. It doesn’t look like it when you watch it thankfully but there was a lot of choreography involved in the making of [my part]. I also love the one shot; it gives the stories a sense of urgency. When you watch the film you feel very connected to the actor, as if you are walking alongside them, sharing their emotions and experiences.”

The film flows in a non-linear structure, organically shifting through scenarios. Industry peers I’ve spoken to about the film have their favourite scenarios, and not necessarily the same one, but each one is unique and creative.

For many years the New Zealand filmmaking community has adopted the practice of first day principal photography karakia. It’s a tradition established by early Māori filmmakers and one continued to this day on nearly every film set. But this required a whole other level of spiritual support.

“As my film deals with the living world and the afterlife it was important to ensure that appropriate protections were placed around my film during shooting so that nothing negative was left at Haranui marae nor nothing bad taken away,” says Maihi, who practiced karakia regularly.

“Scottie Morrison did a rousing karakia at the beginning of the day which spread a beautiful feeling and wairua over the day. I also had a deep sense within that I was reflecting the voice of my ancestors and that they were walking with me in the process.”

It’s this level of respect for the art that sets these women apart and it is reassuring to know that a new generation of wāhine Māori filmmakers are entering the arena. Why? Because the last feature film made by a Māori woman was the groundbreaking film Mauri made by Merata Mita in 1988. Three years before she passed Merata came back to Aotearoa from the United States and began mentoring young Māori filmmakers. Her last documentary Saving Grace – Te Whakarauora Tangata was an examination of the ways Māori could prevent violence against children. Her documentary went to air on Māori Television in 2011. Six years later the issue still haunts us.

While many doors have been opened for Māori filmmakers over the past decade, Maihi says it’s still a tough industry for women. “The budget on Waru was tight and extremely difficult for all departments. To achieve what we did on what we had is an example of the commitment of all involved in this project. It was tough. Film is not our bread and butter, television is. Sadly, many of us can’t even get jobs directing in television either. Something needs to change.

“It’s been good for male filmmakers and horrific for wāhine. It’s one thing to be a man of colour but being a woman of colour is a whole other set of challenges. FYI we are not dumb, we can handle technical things well and we get shit done. Don’t be afraid to give us opportunities in TV and film.”

The New Zealand Film Commission have been touring the country engaging in a consultation process with the Māori film industry in a genuine effort to find ways to uplift Māori cinema. The expert on this is Ainsley Gardiner. As the producer of Two Cars One Night, Eagle Vs Shark, Boy and Pa Boys she’s had a lot of experience and time to reflect on this question. This is what she thinks it will take:

“Collective development, collective producing. We are stronger when we are together.”

Waru was written and directed by Ainsley Gardiner, Briar Grace-Smith, Katie Wolfe, Chelsea Winstanley, Renae Maihi, Paula W. Jones, Casey Kaa, Awanui Simich-Pene and Josephine Stewart-Te Whiu. The film was produced by Kerry Warkia and Kiel McNaughton.