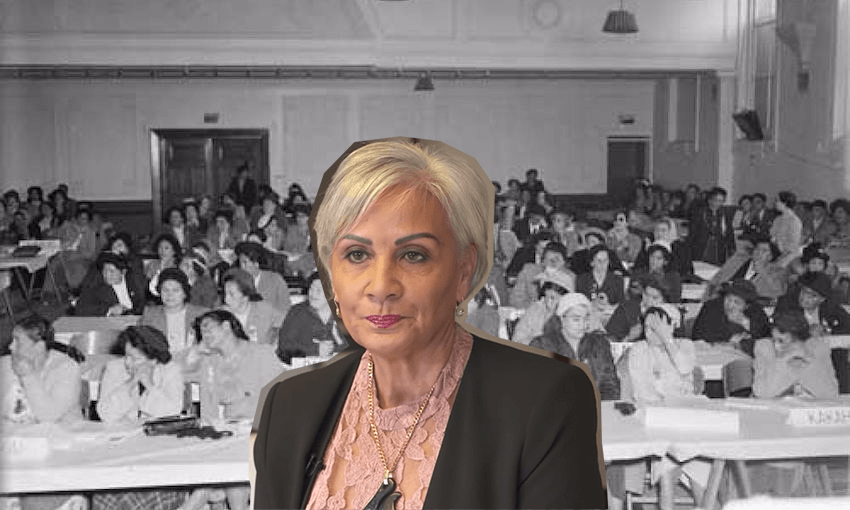

Last week Hannah Tamaki, Destiny Church co-founder and wife of controversial church leader Brian Tamaki, was announced as the leader of Coalition NZ, a new conservative Christian political party seeking election in 2020. Otago University senior law lecturer Simon Connell remembers another equally controversial leadership bid.

In 2011, Hannah Tamaki was nominated for the presidency of the Māori Women’s Welfare League, the organisation famously lead by Dame Whina Cooper throughout the 1950s. It was the first national Māori organisation to be formed, and the first to provide Māori women with a forum in which their concerns could be aired, brought to a wider national audience and placed before the policy-makers of the day.

The National Executive Committee of the MWWL decided to exclude Tamaki from the presidential ballot and omitted to send the ballot to thirteen league branches that the committee regarded as associated with the Destiny Church, justifying its actions on the basis of protecting the league’s constitutional commitment to non-sectarianism.

Tamaki took the league to Court.

Was this a case of the ‘old guard’ improperly attempting to retain control of an organisation in the face of new membership or an underhanded attempt by the Destiny Church to stack the deck?

The High Court perhaps thought that the case was a little of both.

Background

The Māori Women’s Welfare League is governed by the National Council. The council is made up of delegates from each branch. Branches can have one delegate per 10 members, up to a maximum of 10 delegates from any given branch. The delegates vote to elect officers, including the president, who form the National Executive Committee.

In 2009, Tamaki became a member of the MMWL by joining the newly-founded Wahine Toa branch. The Rangatahi Toa branch was also founded that year. In October the next year she was made president of Wahine Toa and in May 2011 she was nominated for the presidency of the National Executive Committee by Wahine Toa and Rangatahi Toa. One month later, 10 new branches of the MMWL were formed, made up entirely of Destiny Church members.

The committee decided to conduct an inquiry into the ten new branches, which was then extended to three older branches: Wahine Toa, Rangatahi Toa and Taumata. They also decided that the branches under inquiry would not be able to attend or vote in the National Council and Tamaki would be removed from the presidential ballot. The voting papers were sent out without Tamaki’s name on them, prompting her to apply for a judicial review.

The case was heard in the High Court by Justice Stephen Kós (now President of the Court of Appeal) on an urgent basis, with the election just weeks away. Tamaki was able to take the league to court because it’s an incorporated society. That means a court can review whether the committee was acting in accordance with the league’s constitution and with general principles for good decision-making.

What about those ten new branches, though?

Prior to June 2011, there were 347 delegates on the National Council. Ten new branches, all springing forth like Athena, fully-formed and ready for battle (or, at least, ready for voting), times ten votes amounted to 100 new votes for the election in August. Although the branches arguably complied with the league’s written constitution, this raised the question of whether they were legitimate, or formed solely to support Tamaki’s bid for the presidency. The judge identified many things about these new branches that gave him “considerable disquiet” about their legitimacy, including:

- they were all formed on the same day, in a single meeting, at the same place: the Auckland HQ of the Destiny Church – on the day of the Church’s annual conference;

- for most of the new members, there was no evidence that they had actually consented to membership;

- membership subscriptions for all the new members were paid to the league by a charitable trust associated with Destiny Church;

- “wholesale importation of people into Tāmaki Makaurau region branches who in fact live elsewhere” – disregard for the whenua is indeed puzzling in the context of a Māori organisation;

- the number of members in each branch fell exactly within the range that led to the maximum 10 votes; and

- the names of almost all members of several new branches happened to fall within certain letter ranges – G-Z in one case, and L-W in another.

The judge suggested that it would be “surprising” and a “statistical freak” if these last two points happened by chance. However, they are more easily explicable as the result of a deliberate dividing up of a list of names in alphabetical (not geographical) order so as to maximise votes.

Where the committee went too far

The court found that the committee had gone too far in removing Tamaki’s name from the ballot, and excluding the three existing branches from voting. The judge accepted that the league had a constitutional commitment to non-sectarianism however, that did not justify removing Tamaki’s name from the ballot simply because she had a strong association with a particular faith – her suitability for president was a question for the voting delegates. Similarly, although the judge thought that there was “strong evidence” of a connection between the three existing branches and Destiny Church, there was no basis for suspending voting for branches that had previously been treated as legitimate.

So, what happened next?

Given the concerns over the ten new branches, the High Court upheld their exclusion from voting. The League’s elections were held, and Tamaki was not elected president. Later, the league reviewed its constitution which, sadly, resulted in a new rift, this time over presidential terms. That saw them back in court last year.

The case was unique in that Justice Kós’s decision also relied on his finding that tikanga Māori (mana, manaaki and tautoko) was to be given as much respect as the league’s written constitution, raising interesting legal questions about unwritten constitutions.

Tamaki has, of course, been in the news recently as leader of the new Coalition New Zealand party. We could look back on the saga of her bid for the MWWL presidency and see a preparedness to bend, and perhaps break, the rules in pursuit of electoral success (in an interview with Paul Holmes after the court case she said she had no regrets). It remains to be seen how she will fare while seeking election as an MP.

This piece is adapted from an article originally published in the 2011 Otago Law Review.