It takes a village to raise a child. But when it comes to tikanga Māori in schools, a few Māori teachers and students are often expected to raise a village.

My experience of being Māori at school was impacted heavily by the death of our Māori teacher when I was in year 10. Before that, the Māori department was thriving. Our Te Reo teacher would have done anything to engage us. We were learning tikanga; things were getting done correctly. Māori wasn’t a mess-around free period. She never wanted us to be the token Māori kids. She wanted us to understand our culture that had been ripped from us. But that flipped on its head when she died.

Your emotion links back to what you believe in, and what you believe in is your tikanga, and your tikanga makes you who you are. We were proud to be Māori when Whaea was our teacher, but to have that stripped away from us, we not only lost our mum, we lost our identity.

After her tangi, no one came to the marae to check on us – not the senior leaders, not the school counsellor. I couldn’t grieve properly because I had to remain strong for my friends. Imagine that level of responsibility on a kid. It was traumatic. Your teacher is in a coffin, and the only support we got was “If you don’t wanna do your work you don’t have to.” I don’t remember teachers treating us tenderly. There was no empathy. And that’s why a lot of my peers were treated unfairly by teachers or seen as acting out, when really they were just grieving.

Before they found a Te Reo teacher, they gave us a reliever who couldn’t speak Te Reo. There was a massive decline in people who came to class. No one was engaging us. Then, when there was Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori, the senior leaders expected us to teach tikanga, to do the haka for them. They wanted to look progressive, but in their own back garden us Māori kids were failing the subject. It showed me that so many places, including schools, only want Māori tikanga when it’s convenient for them.

Every time they would ask me to teach the haka they would say it would be a good leadership experience and give me more opportunities, but I don’t remember those opportunities coming through. When Whaea would ask us to do it she knew there was something more behind it; she would compensate us kids for helping out. But she did it all herself. Most of us knew she didn’t have support, but she didn’t let that burden us. She would shoulder everything and make sure it didn’t come back on us.

After she died, the teacher aide and social studies teacher who were Māori were the only ones dealing with the maintenance of the marae. They did all this cooking for us. They were the only people holding it together. The people at the top were supposed to be supporting them. At the time my anger was directed at whichever teacher took charge of the whole department. They were the first line of defence so all my anger would go towards them.

There was a lot of pressure on the teachers who came after Whaea. They didn’t want another Māori kid to get fucked over. I should have been in the principal’s office, but they protected me. They took care of us in a way that I don’t think the senior staff would have.

The way our school was set up, the marae was across the road from the rest of the buildings. We were always separate and there was never a merging of the two.

To do that merge well, there isn’t one answer. First, you have to be aware and willing to make the effort. Schools simply don’t understand tikanga properly. Teachers actually need to be taught Māori history and tikanga. I would have liked for teachers to see from my perspective. I feel like that’s what the school missed. Colonial points of view were forced onto me and my Māori peers. I didn’t care about these old white men who did nothing for me but take my land. That’s where the questions arise – why weren’t we learning Māori history or Māori literature?

Ihumatao was never mentioned by Pākehā teachers at school. We were going there every day to protest, and the only time you’d talk about it is when some white teachers would start arguing with you about it. It was right in our backyard and we weren’t given the opportunity to understand and study it. In social studies, we did get to study Parihaka. But when I was doing the assessment, the evidence I gathered was kōrero because Māori ways of teaching are passed down through kōrero. My history teacher didn’t validate my evidence because it wasn’t a university cited reference. They questioned the validity, but I got that information from a direct descendant of Parihaka. How can you tell me that their word is not valid, but this British guy who wrote a formal essay about Parihaka is valid? It shows a difference in tikanga. My history teacher probably didn’t understand that.

Then, there’s just obvious racism. I didn’t realise how big it was in schools until I cast my mind back to all those years. I never raised it because I didn’t think about it. But I shouldn’t have had to because I was a kid. I was suppressed in my voice because they only ever wanted me when they needed me. Which makes me feel mana-munched. Which then made me think that this is okay. As much of an activist as I am, I can’t believe they managed to shut me up like that.

When I was in year 13 they finally hired two senior staff members who were Māori and Samoan. Until then it felt like everyone in power was white, even though 80% of the school was brown, so to see that change gave me hope. Seeing two brown faces in positions of power, who were empathetic because they were experiencing what we were experiencing, that finally gave us a voice. The new leaders understood us kids more. Once they came into power more cultural representation came out. Language weeks were emphasised because those two pushed for it. It gave power to the people.

As a youth worker for a Māori-run non-profit, I’ve learned that there is more than one way to teach a kid. Sitting at a desk, head in the books, looking at a laptop: there is more than just that method. Te Ao Māori is about relationships. That’s how we learn – when there’s focus on creating connections and giving opportunities to young people to express themselves. It is about having power with, not power over, which would be a beautiful thing to see between kaiako and rangatahi. Students don’t want to be looked down upon. I don’t want to sit at a desk while a teacher stands in front and dictates over me. I want a teacher who understands me. There should be mutual power. That way you are listening to the kid and what they want to do, while still teaching them what they need to know.

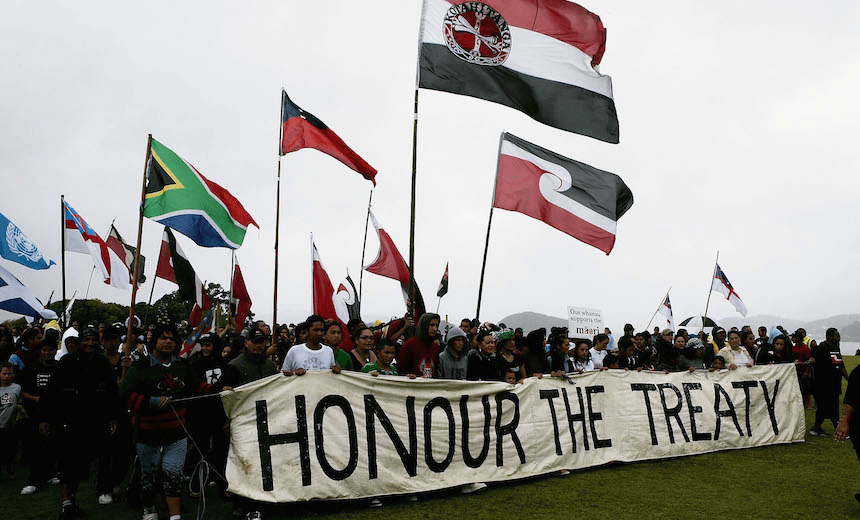

It’s not about becoming better just for Māori, it’s how we get better together as a society. It will take every culture in Aotearoa learning tikanga for things to be okay for us indigenous people. We aren’t forcing it down your throat; we just aren’t letting Pākehā shove colonial aspects down our throats any more. We’ve been forced to understand colonial tikanga. Now we are just trying to help you understand our culture. Everyone must buy into each other’s tikanga.