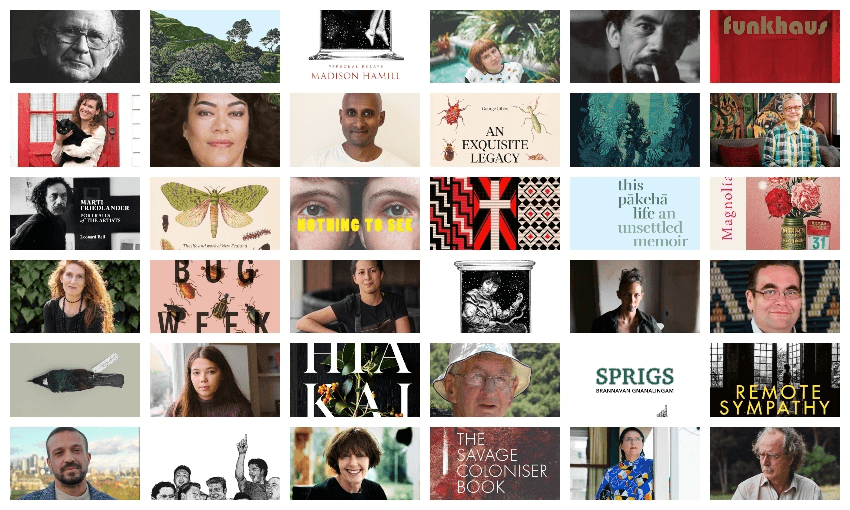

Mōrena! A minute ago the embargo lifted on the shortlist for the 2021 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. Quick stats: 179 entered; 40 made the longlist; 24 of those just bit the award dust. Here are the 16 that remain, followed by analysis from our books editor Catherine Woulfe.

JANN MEDLICOTT ACORN PRIZE FOR FICTION ($57,000 prize)

Bug Week & Other Stories by Airini Beautrais (Victoria University Press)

Nothing to See by Pip Adam (Victoria University Press)

Remote Sympathy by Catherine Chidgey (Victoria University Press)

Sprigs by Brannavan Gnanalingam (Lawrence & Gibson)

MARY AND PETER BIGGS AWARD FOR POETRY ($10,000 prize)

Funkhaus by Hinemoana Baker (Victoria University Press)

Magnolia 木蘭 by Nina Mingya Powles (Seraph Press)

National Anthem by Mohamed Hassan (Dead Bird Books)

The Savage Coloniser Book by Tusiata Avia (Victoria University Press)

BOOKSELLERS AOTEAROA NZ AWARD FOR ILLUSTRATED NON-FICTION ($10,000 prize)

An Exquisite Legacy: The Life and Work of New Zealand Naturalist GV Hudson by George Gibbs (Potton & Burton)

Hiakai: Modern Māori Cuisine by Monique Fiso (Godwit, Penguin Random House)

Marti Friedlander: Portraits of the Artists by Leonard Bell (Auckland University Press)

Nature – Stilled by Jane Ussher (Te Papa Press)

GENERAL NON-FICTION ($10,000 prize)

Specimen: Personal Essays by Madison Hamill (Victoria University Press)

Te Hāhi Mihinare |The Māori Anglican Church by Hirini Kaa (Bridget Williams Books)

The Dark is Light Enough: Ralph Hotere A Biographical Portrait by Vincent O’Sullivan (Penguin, Penguin Random House)

This Pākehā Life: An Unsettled Memoir by Alison Jones (Bridget Williams Books)

Our poetry editor Chris Tse is in raptures over that poetry shortlist – he’s written a separate piece, which we’ll publish later today – but a quick note from me too: this is the first time we’ve had a final lineup featuring exactly zero Pākehā poets.

Another hurrah, re fiction: this is the first time since 2014 that we’ve had a female-skewed final four.

It was a hell of a cull. Goodbye to my forever favourite, Meg Mason, and her novel Sorrow and Bliss – maybe it was a bit much to ask that a book set in the UK, by a New Zealander living across the ditch, would get a serious look-in. But it was glorious while it lasted.

Goodbye, too, to all five debuts on the fiction longlist. Rachel Kerr, Chloe Lane, Eamonn Marra, Amy McDaid, Sally Morgan: it was exhilarating to see newbies swarm the longlist and deflating to discover that they’d all been cut.

That leaves four grandmasters, among them two previous Acorn winners, to tussle over the $57,000 prize.

Catherine Chidgey won with The Wish Child in 2017; this year’s candidate Remote Sympathy is likewise set in Nazi Germany, and if you (like me) really don’t want to read a very long novel about the Holocaust, I urge you to reconsider. I steeled myself to read it recently and it is beautiful. It has a feeling of blooming, lush with nouns and ironies and sentences like these, in which the wife of a Buchenwald officer explores her new larder, marvelling: “My stomach rumbled, and I took an apple and bit into it: cold and sweet, with the faintest taste of earth in the skin … I touched the soft back of one of the birds, which set them all swinging, and for a moment I had the feeling that they were just waking up, that they would tilt their heads and open their wings and begin to fly around the cavernous space, looking for a way out.”

Pip Adam won with The New Animals in 2018; this year’s contender is Nothing to See, a book that’s not linked to The New Animals but is likewise stamped all over with PIP ADAM. Hard to pin down. Shifty, in a good way. Odd and otherworldly in parts, at other times precisely mundane. My favourite section is the bit where a clutch of destitute flatmates make a quiche for an Alcoholics Anonymous picnic. Lots of people were weirded out by The New Animals, especially that long surreal swim at the end; Nothing to See is less disorienting and, whatever “better” means, better. (Both, to be clear, are terrific. PIP ADAM.)

That same year, Pip’s year, Brannavan Gnanalingam made the shortlist with Sodden Downstream. I’m picking him for the win now with Sprigs. His novel has that rare magic: impetus. It’s about a first XV and a high school and a girl. It has a rape scene to break your heart, bundled up in a multitude of other scenes that will break it harder, and Gnanalingam, himself a survivor of sexual abuse, is absolutely scathing and funny and dark and right. Among his many perfect vignettes is one where a female teacher tells some male colleagues she has just been sexually harrassed by students. Instead of asking her about it, the men all chime in with their own petty, ridiculous stories of being shamed out by the kids. They’re so wrapped up in their own voices, their own egos, that they don’t notice she’s walked away.

I wish I had read this book when I was 16, and that the boys and the teachers had read it too.

But then there’s Bug Week. Airini Beautrais has pulled off the return of the short story – this is the first collection to make the finals since CK Stead in 2017 – and she’s done it with a book that coalesces around a brilliant, whirring female anger. “I felt compelled to write about the things I wrote about,” Beautrais wrote for us last year. “And that included rape and intimate partner violence. I felt that my place in the literary ecosystem was strongly affected by the fact that I was a woman – a woman in her 30s, a single mother in a small town, a survivor of abuse. I can’t separate my writing from my trauma and my anger. I’m a very angry person a lot of the time. There’s a big artistic risk in that, but I also think there’s massive, explosive artistic potential.”

Awful lot of trauma bundled up in those four finalists. The Holocaust, of course, in Remote Sympathy. All sorts, as experienced by women (even after death) in Bug Week. Rape and rape culture, and racism, in Sprigs. Nothing to See – it’s hard to nail down, of course (PIP ADAM) but let’s say addiction, inequality, isolation, big tech.

Congratulations Victoria University Press! On the maths alone this year is a triumph for VUP, which published three of the fiction finalists, two of the poets, and Madison Hamill’s stupendous book of essays.

Congratulations Madison Hamill! She’s 25 and a goddam genius (you can read one of the memoir-ish essays from her book here) who just casually saw off CK Stead and Brian Easton and Martin Edmond, and could well now win the general non-fiction category. But could the fact Shayne Carter won with memoir last year, and was also published by VUP, count against her? The general non-fiction category is in the impossible position of embracing all non-fiction books that don’t have pictures, which means the poor old judges are weighing big biographies like Vincent O’Sullivan on Ralph Hotere against essays like Hamill’s, against a history of the Māori Anglican Church, against Alison Jones’ thoughtful, textured memoir. Judges are meant to simply pick the best book, but there may be an undercurrent of wanting to pick something quite different from last year.

Onwards to the MitoQ Best First Book prizes, which dole out a very decent $2500 to debuts in each of the four categories.

Congratulations Monique Fiso! She’s all but guaranteed to pick up a MitoQ best first book prize given that her groundbreaking Hiakai is now the only first book left in its category. (Honourable mention to Sarah McIntyre, whose gorgeous debut Observations of a Rural Nurse is somehow missing from the shortlist. You can see images from her book here.) Fiso also has an extremely good shot at winning the overall prize for illustrated non-fiction – although awards stalwart Jane Ussher may stare her down with her mesmerising museum of a book, Nature — Stilled.

Congratulations to the poetry contenders, Jackson Nieuwland and Natalie Morrison, neither of whom made the shortlist, but no matter.

Congratulations to the general non-fiction contenders: Madison Hamill, genius, and Anglican minister and historian Hirini Kaa.

And congratulations and commiserations to those five wonderful debut novelists who stormed the longlist only to fall short. Best first book in this category is going to be an absolute bunfight. I suspect it will go to McDaid or Marra, but I hope it goes to Rachel Kerr for her quiet, sharp little novel about caring and compassion and the unseen work of women. Victory Park has a stunning cover, too. Maybe the best of the lot.

Winners will be announced at the Auckland Writers Festival on May 12 with much pomp and, hopefully, an in-real-life ceremony. You can buy all the books above at Unity Books Auckland and Unity Books Wellington.