All week this week we feature tangata whenua writings to mark Waitangi Day. Today: Vincent O’Malley reviews a new history of the battle of Gate Pā.

Head up Cameron Road, one of Tauranga’s main arterial routes, a few kilometres out of the city centre and you drive over one of New Zealand’s most important historical sites. The road, named after Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron, commander of British forces in New Zealand between 1861-65, was one of many built over former pā used during the New Zealand Wars. Ōrākau, Rangiriri and other important sites suffered similar indignities. Why remember, the attitude seemed to be, when Pākehā could instead obliterate any physical remnant of such places and just pretend history never happened here? It’s the Kiwi way apparently.

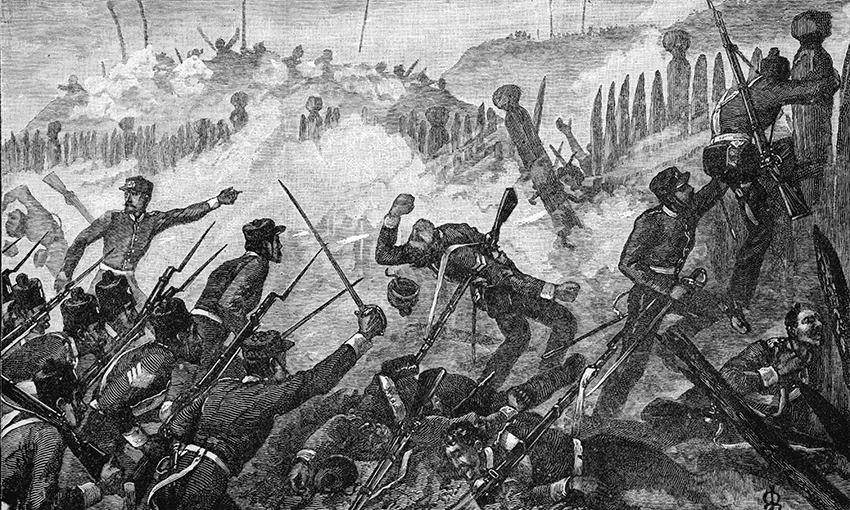

In the case of the Cameron Road site there was added incentive to forget. Despite being outnumbered seven to one and enduring perhaps the heaviest bombardment ever to take place on New Zealand soil, Māori inflicted a humiliating defeat on their British foes, led by Cameron, on this ground. The battle of Gate Pā/Pukehinahina on April 29, 1864, was described by one contemporary observer as the “most disgraceful episode in the history of the British army”.

At a loss as to how to explain such a stunning reversal, some figures blamed cowardice. Others pointed to grievances among the rank and file soldiers against their commanding officers. Anything but Māori military genius. Either way, a crushing British victory at Te Ranga, several kilometres further inland, seven weeks later helped to ease Pākehā pain, besides paving the way for sweeping land confiscations at Tauranga.

It’s a tragic story and one that most New Zealanders probably have little or no knowledge of, given how few people learn anything of our history at school. Buddy Mikaere, a former director of the Waitangi Tribunal and descendant of one of the Pukehinahina defenders, along with Pākehā military historian and New Zealand Army officer Cliff Simons, sets out to redress that in their new study. The curious question mark in the title is apparently intended to signal the authors’ belief that Gate Pā “was a classic Pyrrhic victory where the battle was won but the war was decisively lost”. James Belich would probably beg to differ on this point, but there is no real effort to engage with his arguments.

Victory at Gate Pa? is not the kind of work to get mired in historiographical debate. A relatively short work, it appears pitched more at school rooms than scholars of the New Zealand Wars. Nothing wrong with that and it mostly does the job. But it might have benefitted from closer attention to detail at times. A few random examples: Rangiaowhia was attacked on February 21, 1864, not the 17th; Matene Te Whiwhi did not travel to England with Tamihana Te Rauparaha; it’s the New Zealand Settlements Act, not the Native Settlements Act.

The authors are on firmer territory when they focus on the war at Tauranga. In January 1864 a British military expedition landed at Tauranga, taking possession of the Te Papa peninsula that had been home to a Church Missionary Society station since 1835. The expedition was intended to block a vital supply route that was being used to send additional fighters, food and weaponry to Waikato Māori confronted with the Crown’s invasion of their territory.

Tauranga iwi had strong connections with the Waikato tribes across the Kaimai Range and had gone to their assistance after British troops attacked Kīngitanga-controlled territory in July 1863, making common cause with Tainui in their efforts to defend their lives and lands. Governor George Grey and his advisers hoped to draw them away from the Waikato by landing a force at Tauranga. Even before any fighting there, Tauranga had already been identified as the likely location for one of a series of military posts stretching across the island to Kāwhia or Raglan, and ministers were known to covet the fertile lands around Tauranga harbour.

Many Tauranga Māori, not unreasonably, interpreted the arrival of troops in their midst as signalling imminent war and began building defensive pā in preparation. When nothing further happened, a formal challenge was issued, naming April 1 as the day of the fight. Along with the challenge was a remarkable letter setting out the laws that would be respected in any clash. Sent to the commanding officer of the British troops at the end of March, it declared that wounded soldiers would be spared so long as they made it clear they no longer wished to fight and that those who surrendered would also be saved. Civilians, including all Pākehā women and children, would not be harmed.

British officers did not know quite what to make of this document (which Mikaere and Simons suggest could be traced back to arguments advanced during the first Taranaki War of 1860-61) and ignored it altogether. But on April 16 1864, Tauranga Māori began constructing a new fortification on a ridge about five kilometres inland from the Te Papa station where the missionary estate ended and Māori land began. The troops called it “the gate pā” because of a gate that ran along the boundary. Māori knew the ridge as Pukehinahina.

Pene Taka Tuaia, a veteran of the 1845-46 Northern War, had seen at close range Kawiti’s remarkable pā at Ōhaeawai and Ruapekapeka. His Gate Pā design initially failed to impress British officers. Viewed from above ground and a distance, there appeared little to it. Cameron ordered the pā to be bombarded from first light on April 29. With little sign of activity from inside the pā, and convinced all inside might well be dead, by late afternoon he sent forth a storming party of 300 soldiers and sailors.

The British entered the pā with ease, encountering minimal resistance. Suddenly, a tremendous but invisible fire was let loose upon them. The Gate Pā defenders were firing from concealed positions beneath the feet of the storming party, inflicting significant casualties. Panicked survivors turned and attempted to flee but were soon mixed up with further reinforcements sent forward by Cameron. Matters quickly became chaotic. In all, over one-third of the storming party ended up as casualties, 31 killed (10 of them officers) and 80 wounded. Māori losses are harder to gauge but might have been between 19 and 32 killed and 25 wounded.

The authors reject the theory (advanced by Belich) that this was a deliberate and brilliantly executed trap, arguing that it was just the way the battle unfolded. But Hori Ngatai, one of the defenders, later recalled that they had been under orders from their leader, Rawiri Puhirake, to hold fire until the signal was given. Whatever the case, around 230 Māori fighters had crushed a British force numbering nearly 1700 in total.

During the evening the defenders slipped out of the pā, enabling the British to enter and inspect the site in closer detail. They soon realised that they had greatly underestimated the defences, built to withstand an enormous artillery assault and including intricate features such as zig-zagging trenches that would make it impossible for any intruder to fire along them. Gate Pā/Pukehinahina was another testament to Māori military engineering skills.

As the British entered the pā the following morning, some troops feared for those they had been forced to leave behind in the mayhem of the previous afternoon. None had been maltreated, however, and reports began to circulate of acts of kindness shown the men. At least one of the gravely wounded officers, Colonel Booth, had been given water as he lay dying inside one of the trenches. There are various stories as to who had been responsible for this deed, although the remarkable wahine toa Heni Te Kiri Karamu, the only woman in the pā at the time of fighting, later described doing so. There seems no reason to doubt her version of events.

The rules of war drafted by Henare Wiremu Taratoa, a young lay reader in the Anglican Church, had been scrupulously respected by the Pukehinahina defenders and that fact came to be widely celebrated and memorialised. Taratoa himself died at Te Ranga on June 21 1864, and was found with a copy of the rules on his body, along with the Biblical injunction from Romans 12:20: “If thine enemy hunger, feed him; if he thirst, give him drink.” Along with Rawiri Puhirake, he was one of as many as 200 Māori killed in the British attack.

An area of 290,000 acres was subsequently proclaimed as subject to the New Zealand Settlements Act. 50,000 acres was confiscated outright and a further 93,000 acres at Katikati and Te Puna became subject to a non-voluntary Crown “purchase”. Further warfare, known as the Tauranga Bush Campaign, and involving the scorched earth destruction of multiple Māori villages in the area, followed in 1867 when “unsurrendered” tribes sought to resist the survey of confiscated lands outside the area the government had agreed as the boundaries.

In a poignant chapter offering a personal perspective on the wars, Mikaere recalls how his own Ngāi Tamarāwaho hapū were confined to a couple of tiny reserves, and forced to squat on confiscated lands on the fringes of Tauranga city until its growth from the 1950s meant they were pushed off these places too. For the various Tauranga iwi (Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Ranginui, and Ngāti Pūkenga), war and confiscation were not just events from the past: they lived with the consequences every day. In many ways they still do.

Cliff Simons offers his own tale of how he came to embrace New Zealand Wars history, after learning nothing of these conflicts during his time at school. Ironically, it was only after joining the New Zealand Army, which decided in the 1980s that this history was sufficiently interesting and important to make a compulsory part of officer training, that he began to study them. Perhaps we should put the army in charge of our education system.

Mikaere and Simons were together heavily involved in organising the highly successful 150th anniversary commemorations of the battle of Gate Pā/Pukehinahina in 2014, which included redevelopment of the reserve that includes part of the battle site. Tauranga may not have (or, incredibly, even want) its own museum. But it does have this site of immense historical significance on its doorstep that is finally beginning to receive a measure of recognition and protection. One day perhaps all children at Tauranga might learn something of what took place at Gate Pā/Pukehinahina during their school years. If they do, this book will provide a useful teaching aid for a history Pākehā have shunned for much too long.

More from Waitangi Week:

The Queen is dead, or may as well be: Morgan Godfery on the case for a NZ republic

Victory at Gate Pa? by Buddy Mikaere and Cliff Simons (New Holland, $35) is available at Unity Books.