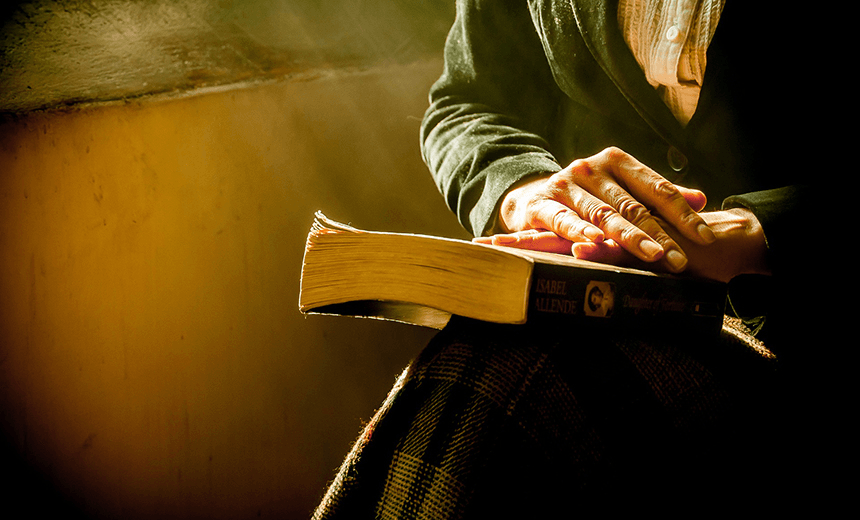

‘The book is the catalyst, the key.’ Scarlett Cayford on the secret society of book clubs.

When I moved to London, I joined a book club. It was an easy decision to make – I wanted to meet new people, I’m terrible at most team sports, and I have a lot of opinions about the printed word. I was 25, just on that cusp of confessing to true adulthood, and situationally far from the kinds of scenarios in which friendships form easily (classrooms, lock-ins, cleaning down the bar at 3am). It’s not easy to make friends in London, where people have calendars stacked deep with dates, where the long-term residents have closely-guarded circles of cohorts, where you might live a 90-minute commute from the one soul you meet who seems to like you. I sound like I’m trying to be cute, but I was going on nights out with my boyfriend’s group of friends and bursting into tears at 1am because I was so jealous of how much they all liked each other.

I was lonely. I needed what the internet would call “a safe space” and what I would call “someone to fucking talk to”. I needed a book club.

Finding a club was easy – I Googled “London Book Club”, clicked on the first link, emailed the founder and showed up at a pub 10 minutes down the road from work, where seven women of varying ages were sat outside, discussing Flight Behaviour by Barbara Kingsolver. I pulled up a chair, told them my name and Twitter handle, slapped my copy of the book on the table. Twenty minutes later, we’d ascertained that I was the only person with anything positive to say about the book, imbibed the better part of six bottles of wine, and learned that one member of the book club had once had oral sex performed on her by a female rock star in the back of limousine. I left when the pub closed. I’ve gone back nearly every month for the last four years.

Lance Armstrong once wrote It’s Not About The Bike. Book clubs, I would argue (convolutedly, since my key source text here is a book) are not about books. The book is the catalyst, the key. The book is the reason to form the Facebook group. The book exists as a sensible excuse to sit around a large sticky table on a Tuesday night, knocking back pints, talking candidly with strangers. The book is the uniting factor in a room full of faces who might have bypassed each other on the street, once, but would never have spoken, were it not for a few shared opinions on the flaws of the protagonist and the overuse of rape as a plot device (we once read 11 books in a row that featured a rape until, desperate, we picked a Bill Bryson). The book is a symbol to unite around. The strangers are the real reason you’re there.

I’ve been in a few different book clubs, but the London one is the one that has stuck. I think there are a few key elements to this. The first is the formula: once a month, with the book decided upon by whoever was at the previous meeting. The second, the destination: a local pub, with a private room, and friendly staff to deliver cheesy chips and fish finger sandwiches upon request. The third is the utter devotion of the founder, who shows up without fail, talks incessantly, and is unfailingly generous with her time and commitment. Lots of people form book clubs on whims; a desire to connect, a motivation to read. I’m a member of Meet Up, an internet platform on which people conceive of and create a multitude of clubs devoted to books, or writing, or climbing, or dogs, or masturbating, or other things. Most of them falter after a few months, when the number of attendees drops, or the weather gets good, or bad, or life happens. Not mine. I’m lucky.

I don’t remember every book we’ve discussed, but every now and again there comes a book that sets a fire under us. Like The Power, Naomi Alderman’s electric dissection of what happens to all sectors of society when the balance of gender power flips. Intricately put together, with central characters that sing, it’s not exactly surprising that it was a novel that spoke to us – and to plenty of others, given that it went on to win the Bailey’s Prize. We gathered together over that book like members of a secret society drawn together by some sort of cataclysmic event; like keepers of a covenant made suddenly privy to life-changing information. We were just in a pub, sharing food, but as we spoke of Allie, Roxy, Tunde, Margot, it felt like we had discovered our own secret, powerful history. And yes, as we got drunker, and picked the bones of the meat clean, we spread our palms, felt for our own skeins, felt the lack. Alderman would have liked it, I think.

And then there have been the books that brought to light the rifts. You can’t bring 30 opinionated women together, present them with convoluted fictional tales, and expect them not to hold differing opinions on the subject matter. Jilly Cooper’s silly, sexy Riders for example, sorted the British from the not-so-British – those who found only fun in the polo-pegged romp, and those who could not read without shrinking from the ugliness in a sport that relies on hierarchy and heritage. In London, you can get by without letting it surface, most of the time, everyone brought to the same level by endless working hours, the fatigue of the tube, the fact that none of us can afford much of anything. After some discussion of the book, it became apparent that we were not all the same.

Or The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer. This novel depicts four lives revolving around each other, and one awful incident, through childhood and into adulthood – on the surface not much more than a drawn-out dissection of the lives of a group of friends – and provoked such diametrically-opposed opinions and aggressive discussion that, in the weeks to follow, blog posts were published on book club decorum. Appropriate, perhaps, given Wolitzer’s commitment to the theme of entertainment in tragedy; a bit of a case of life imitating art as book discussion devolved into personal attacks, all of us assuming our own stereotypes: the victim, the bystander, the aggressor… Our incident wasn’t quite on the scale of The Interestings, but it was still a blow to the book club. One girl never came back.

I’m making it sound like our own sort of Secret History, but it’s not a secret society. You could come. You should come. My book club has an open door policy. There is a regular influx of the curious literate, sticking their head awkwardly through the door, pulling up a chair, unloading some opinions, problems, work beef and Tinder fails. Some of them stick, but most of them don’t, because people join book clubs for any number of reasons, and it’s hardly ever because they simply cannot go another moment without having a conversation about a mandated book.

There are patterns to their arrivals – February’s meeting, for example, is always flooded with new faces, brought to our circle by an earnest New Year’s resolution that they weren’t organised enough to follow up on in January, and will have forgotten come March. In 2015, so many people turned up to discuss The Rosie Project that we had to form concentric circles in order to all fit in a room. A book club within a book club within 20 damp one-timers, shouting to make themselves heard in the windowless pub. It wasn’t a success, but it didn’t matter – one or two meetings later it had dropped back to the quorum, not because we were unfriendly, but because most things don’t stick. You go to the gym four mornings a week for a month, and then you stop. You double-cleanse every night before bed, and then you don’t. You Skype your parents every month. You save £100 a month. You floss. You stop.

I’m glad when they stick, because London loses people all the time, especially when the median age of your book club sits around 30. People flee to purchase homes, or procreate. They relocate to Dubai with exciting jobs, or they do something as mundane as move house and find that commuting through London on a Tuesday evening isn’t something they’re prepared to do. An open door makes it as easy to leave as it does to arrive.

My mother’s book club has a very different format, and the door to it is largely closed. Inviting strangers to a pub on a busy street in London is very different to ushering them into your front room, and so her book club is full of friends who know each other well – not just their opinions on fantasy and fiction, but on funerals and family tensions. I’ve got four years under my belt at this book club, but that’s paltry compared to the relationships that these women share. More structured, too, is their book choice – instead of quickly downloading the Kindle version three days before the meeting and reading it over four slightly-extended lunch hours, they select the book they wish to read from a catalogue, and it is sent to them together with discussion questions, to be returned when the night is complete. About 10 years ago my mother decided she had too many possessions, and did her best to cease buying books – this format, then, sits nicely with that life. My life is the opposite, stuffed with proof copy paperbacks stacked on the floor, because I can’t free up a Sunday afternoon to get to Ikea and buy a bookshelf. Sometimes, I’d like to swap with her. Sometimes, I imagine she wishes the same.

They’re different, but the same: both made comfortingly regular by the formula, the location, the founder. In some ways, my pub-table book club is as old as the hills. Modern day book clubs have had a much more serious renovation. You don’t have to be the same sex, or age or gender; you don’t have to be in the same room, or the same country, or even speak the same language. The internet has become the world’s book club, with sites like GoodReads making a thousand opinions on your current volume available to you. The structure has changed, too – the leaders are shiny-haired YouTubers who look like human manifestations of My Little Pony, thrusting volumes of sex and disappointment and scandal on millions of eager teenagers who are (suddenly, delightfully) willing to admit that they read for pleasure. Zoella has a book club. Emma Watson has a book club. Reese Witherspoon. Sarah Jessica Parker. Florence Welch. And while I’m not dumb enough to dump on them – anything that encourages bonding over reading is fine by me – I do think that something is lost from the IRL meet-ups. Eye contact. Smells, sounds. Booze, yes, but also the distinct pleasure of watching someone’s throat redden as they discuss Jilly Cooper.

When I tell my boyfriend that I have book club that night, and that I won’t be home late, and that I won’t need dinner, he rolls his eyes. He knows far better than I that I will arrive home some time after 11 o’clock, demanding a wrap stuffed with as much cheese and sour cream as it can physically contain. I always start my book club nights the same way: grumpy, because it’s Tuesday, and I’ve just had to navigate Holborn in the rain. Then I order a large glass of viognier and a plate of cheesy chips, and the tension that’s been building around me since I first squeezed on the Northern Line at 8am that morning dissipates a bit. I’m always early, because I’m always early to everything, and so the conversation is largely gossip for the first 20 minutes – who’s been fired, who’s been to which party, who’s moving house. It’s at this point that I must give another book club recommendation: endeavour, whenever possible, to make sure your book club is made up of people who live more interesting lives than yours. Mine is stuffed to the gills with journalists and media types and I’ve heard tales you wouldn’t believe. It gets you under the skin of things. It gives the sensation of being in.

I don’t know many men who regularly participate in book clubs. There is only one regular male attendee at mine, a straight Englishman who works in the beauty industry and appears to enjoy his rare privilege. There used to be more: a tall man whom everyone tried to set up on dates; a political journalist who rarely gave anyone else the opportunity to express their opinion, a marathon runner who liked to cook. They have fallen away where others have stayed, and that’s a bit sad. Much more entertaining are the one-time males who stumble into the club, drawn in by the internet and the appeal of chatting about Australian mysteries in the shade of oak trees. Some seem to have a good time; others pretend to go to the bathroom, then fail to return (true story). We don’t miss them, but we’re glad they came.

I have no doubt there are men who like book clubs. Perhaps there are, in some parts of the world (probably London), male-only book clubs, populated by erudite specimens who wax lyrical about Camus over tumblers of whiskey, neat. Maybe those same book clubs are occasionally accidentally attended by hapless females who, after 15 minutes of discussion about the importance of the male narrative, fake menstruation and flee to the nearest door. I’ve just never heard tell of them, and so I have to assume, with no evidence to the contrary, that book clubs are largely a woman thing. That makes them an outlier, as far as I’m concerned. There are probably more male-focused football clubs and rugby clubs than there are female, but there are still plenty of the latter. There’s no reason in particular why books, and the reading of them, and the talking about them, should be a singularly ladylike activity. In fact, if we’ve learned anything from the thousands of oil paintings that depict barrel-stomached bearded men stood by a table, one fat finger marking a spot in a fat, red leather book, books are as much symbols of male intelligence and bravery as lions carved into the armrests of really big chairs. Additionally, most book clubs also include the consumption of large quantities of your chosen liquor – something large bonding bands of boys also tend to favour.

So I’d be stumped, if it weren’t for something I noted earlier: book clubs aren’t really about books.

They’re about bonding, and they’re about conversation, and they’re about sharing secrets. I can’t speak for all, of course, but the book clubs I‘ve attended usually end up involving about 30 minutes of intense book discussion (made shorter or longer in duration by how much disagreement there is. I urge you never to read a universally-beloved book, because you’ll run out of conversation points in 15 minutes or less: Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, I’m looking at you), and nigh on three hours on the subject of different sexual proclivities. Men talk over pints, but they don’t delve into things like women do. They don’t concede to intimacy immediately. Book clubs are the bathroom at the nightclub – the place where you can stare into the eyes of a complete stranger and tell her, unabashedly, that she has the best breasts (opinions about Eleanor Catton) that you have ever seen (heard).

It’s impossible for me to say that everyone can get as much from a book club as I have. If that were the case, we wouldn’t have had dozens and dozens of hopefuls turn up, sit for an hour, then walk away forever. It takes time to find your people, and life is busy: for some, it is not possible to commit to reading a book a month, or to turning up at the same time every four weeks. Things get in the way. That’s the thing about books though: they fit well in gaps. Slid into the smallest pocket of your handbag or coat, they fill 10 minutes on the tube, or 15 in the waiting room at the doctor, or hours at a time when you don’t have the mental space for things that are actually happening. That’s when Elizabeth Gilbert, Naomi Alderman, Neil Gaiman step in.

Book clubs can be like that, too: unassuming. That’s why I wish more people would stick with them. An hour a month. You don’t have to be athletic to attend a book club. You don’t have to be loud. Just pull up a chair, say your name. Sometimes I skip mine, but I always know I’ll go back. If I leave this city and make another my own, I’ll find it somewhere else. The sticky table, the glass of wine, the circle of faces, the book. It’s my safe space. It’s my favourite place.