An essay by Patrick Evans to mark his new novel The Back of His Head, which imagines that “a complete and utter prick” has won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

‘No entry to all vehicles, writer at work’ – the sign in the Jerusalem street the writer known to the West as SY Agnon lived in. One immediately thinks of Frank Sargeson and his safe little Takapuna cul-de-sac, cruelly chosen as an exit from the new harbour bridge in the later 1950s: standing in his cottage five years ago I listened to everything rattle and clink as trucks roared past just outside, where the hedge once was, and close to where Frank, inurned, still is, under a locquat tree.

It’s the dream of each of us to live on Agnon’s street and our fate to live on Sargeson’s. We yearn, all of us who read and write, to live in a society that values literature as much as we do: as a crucial cultural activity that tells us we’re civilised human beings and that life is rich, purposeful and imbued with meaning. Everything that has ever had value for us, our very sense of who we are and what the world is, goes on living in words and sentences and books, before us, during us, after us. Literature is what got us here; we’ve been shot through with it.

When Agnon went on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1966 he became part of another process by which the significance of imaginative writing has been marked in Western societies. In many of the citations given each laureate, the Prize of Prizes shows off its roots in Western liberal humanism and particularly in our long-held belief in human perfectibility: ‘evidence of lofty idealism’ (Sully Proudhomme, first Laureate, 1901); ‘an idealistic philosophy of life’ (Rudolf Christoph Eucken, 1908); ‘lofty idealism, vivid imagination and spiritual perception’ (Selma Lagerlof, first woman laureate, in 1909); ‘lofty idealism … and … sympathy and love of truth’ (Romain Rolland, 1915); ‘profound human sympathy’ (Anatole France, 1921); ‘both idealism and humanity’ (G.B. Shaw, 1925); ‘humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought’ (Bertrand Russell, 1950); and so on, right through to Patrick Modiano, last year’s winner: his forté, apparently, is grasping ‘ungraspable human destinies’.

All of which seems to have left New Zealand rather out of the loop. Even Australia, land of dingo, koala and Tony Abbott, has its own literary Nobel Laureate in Patrick White (‘epic and psychological narrative,’ 1973). According to no less a critic than Simon During, White’s series of heroic lunges will mean less and less to Australians as time goes on; but significant enough they seemed to me when, a student in rumpty, unlettered old Christchurch in the 1960s, I discovered them for myself in the Christchurch Public Library. Riders in the Chariot (1961), his sixth novel, had me caught in its first few pages, with their mannered, self-consciously-heightened description of Miss Hare, orphaned spinster oddball living in the remains of Xanadu, her family home, on the fringes (of course) of society and soon to be joined by other Significant Outsiders: Mordecai Himmelfarb, refugee (of course) from Hiter’s Europe, Alf Dubbo, Aboriginal waif and refugee from a pederastic (of course) clergyman, Ruth Godbold, humble (of course) washerwoman, housekeeper and reproach to us all. I turned the pages, open-mouthed: was I about to be vouchsafed the Meaning of life so early in my own?

It is Dubbo’s paintings – earthy, instinctual, primal, unfettered – ‘authentic’ – that capture the Ezekiel-lite riders of the title as they blaze across the sky, visible to this four alone as a mark of their status as an Elect up against a jolly, brainless Aussie Preterite who eventually crucify the Jew and burn his house down – in fact, one of these damned is actually called Mrs Jolley: ‘I like a fire,’ she tells her friend Mrs Flack as they watch the Jew’s timbers burn. So significant! – so full of compassion, of idealism, of the unquestioned values of T.S Eliot’s ‘thousand years of European continuity’: of Western liberal humanism, in short – values simply celebrated and reaffirmed. Of course that’s what we believe: which of us, after all, does not wish to be perfected, which of us does not want to move towards the light?

At the time I was devouring White like this all we had to match such vaulting ambition amongst our own fiction-writers here across the ditch, it seemed, was Maurice Shadbolt, a writer of considerable output and ambition but one somewhat underpowered, rather like those light three-wheeled breadvans the British used to build around a Raleigh motorcycle just after the Second World War. The title of Shadbolt’s first collection (The New Zealanders, 1959) bespoke his assumption that he was speaking for us all without even having to be asked. His novel Strangers and Journeys (1972) was probably his greatest attempt to write a work of some significance in what was seen at the time as a race to bring out The Great New Zealand Novel: but an attempt, in the end, was all it was.

He had great ideas for significant projects, someone once said: the pity was that he then went on to write them. Driven, remorselessly, by what Ian Wedde (in a scathing review) called ‘the will to write’, he had far less imaginative and expressive power than White, alas – and, in all truth, far less than Wedde himself (see, for example, Symmes Hole, 1988). Worse, Shadbolt had at times such a cloth ear that entire suits of clothing might have been made from it. Don’t mind the quality, feel the width. Writer at work.

*

Speaking of width, it’s time to ask who the Gnomes of Stockholm might have chosen had they been given a map that actually included New Zealand – who we think might have deserved to get that phone call the secretary to the Nobel committee makes a few hours before each Announcement, bringing joy to the laureate’s publisher and bank manager alike?

Well, Janet Frame, most obviously, since she was nominated a number of times, according to her Official Biographer. As I remember it the process began in the early 1980s, through PEN, and eventually, late in 2003, she was rumoured to be actually in the run-off for the award (though how did anyone know? – famously, the Prize is not shortlisted). This was a few months before she died; several times before that she’d been thought (those rumours again) to be ‘close’ and also to be appalled at the prospect of actually getting the Nobel. ‘Oh, Christ,’ was the (probably laundered) response of Doris Lessing when hovering reporters told her of her win in 2007, as she returned home from Waitrose’s, her shopping bags crammed with bargains. All that unwanted attention – all those people, too, with their vile, vile bodies, their uninteresting interests, their frightful accents and loud voices, their shocking teeth. Actual people, the writer’s perennial nightmare: resolved most memorably by Edna St. Vincent Millay, who announced that she loved humanity but hated people. Writer at work.

Frame’s vision of the world was remorselessly bleak – truth-telling to a scrupulous, unbearable extreme. Perhaps this is where her work fell short when confronted by the Gnomes of Stockholm?

I always remember the class of students who turned to anti-depressants after I made them read her work: ‘We liked Janet till we read her,’ one of them said, helplessly, when I asked what the problem was. Did they mean the scene at the end of The Adaptable Man (1965) in which a chandelier, just lit, collapses onto diners at the table below, killing or maiming them all? Or the mortality-obsessed beetle in Scented Gardens for the Blind (1964), yakking on and on about death? The mental hospitals of Faces in the Water (1961)? The death camps at the end of Intensive Care (1971), perhaps? Or the surgically-mutilated one-eyed dog in Daughter Buffalo (1972), which watches its owners bonking?

I’ve often wondered – if she did indeed come close to landing The Big One in the second half of 2003 – what the Nobel committee members, reading her, made of our ‘modest island nation’ (Bill Manhire’s wry description of us). Would a win for her have been quite what Helen Clark had in mind back then for branding our country’s kiwi fruit exports?

The other writer whom the committee might have taken very, very seriously, it has become Abundantly Clear To Me (a Bill Rowling phrase, that, by the way, since we’re talking of kiwi fruit), is Allen Curnow. This thought is not original to me, and is shared by others who have long known his worth. His long life (1911-2001) had that sense of being a work of art, with a beginning, a middle and an end (see Yeats, ‘Under Ben Bulben’). It moves from the vatic utterances of a self-appointed poet laureate in what someone has called his ‘state poems’ of the war years (‘Not in Narrow Seas,’ ‘The Unhistoric Story,’ ‘Landfall in Unknown Seas’) through a long, consistent middle period to the triumph of An Incorrigible Music (1979), centred on the magnificent sequence ‘Moro Assassinato,’ in which the poet imagines himself into the kidnap and murder of the Italian politician by the Red Brigades, which he sees as a rhythmic echo of the Pazzi conspiracy in the same place 500 years before.

There’s a resignation to the world in the poetry of this sequence, an ablation of ego and that ‘will-to-write’ that eventually yields the serene, clear-headed poems of Curnow’s final collection, The Bells of Saint Babel’s (2001), which seem to have been cleansed to utter purity: so brief, so simple: in the best sense, his senilia. He also fufilled – more than fulfilled – the role of Magus that seems to be implicit to the award of the Nobel: this more by the example of his poetry than by his many pronouncements (particularly earlier in his career) about How Poetry Should Be Written.

He became someone whose voice you couldn’t get out of your ear: either you were doing it his way, or you were trying as hard as possible not to do it his way. Reading him, we are always aware of what he called his ‘second unlicked self,’ his country. He was not ‘just a poet’.

Which of our more recent writers might we think of as worthy of that phone call from Stockholm at some stage of their lives, in the parallel universe in which New Zealand is as significant to the world as we collectively imagine it to be? My candidate (and others’, too, by the way; I’m indebted to my colleague Paul Millar in my thinking here) is Patricia Grace.

*

Someone once told me of sitting in a room full of elderly Maori on a marae as Patricia read some of her earlier stories to them. They purred with self-recognition, I was told, and at some points laughed themselves silly, frequently in places a Pakeha mightn’t expect: and suddenly the English she was writing started to sound to me less like ‘English’ – denoting a language of a dominant discourse – and more like ‘english’, uncapitalised, the many versions of the language spoken beyond the sort of streets city councils might block off to protect a Writer at Work.

You might say that where other Maori were writing ‘out,’ for a Pakeha audience first and a Maori audience second (if at all, in some cases), Grace has been writing ‘in’, and, crucially, addressing the conundrum of how to create a literature about dominated lives from within her country’s dominant discourse. Her novels imagine Maori experiences into words – a mixed marriage in Mutuwhenua (1978), women singing their men off to war in Cousins (1992), the battle at Monte Cassino in Tu (2004), more – but it is in her many unassuming short stories that I think her real significance lies, not least in rendering some of the most convincing dialogue ever written by a New Zealander. In effect, she has invented a language, one accessible both to Maori and to Pakeha readers across the world.

Compare this with the language Patrick White invented to write in – vatic, hieratic, deeply rooted in the European imaginary, a priestlike anti-vernacular devised largely for other priests – Writer at Work – and as resistant to the reader, in its own way, as Janet Frame’s. Why, then, did people unquestioningly nominate Frame for the Nobel Prize – she who described herself, according to Michael King, as ‘New Zealand’s greatest unread writer’ – and not Patricia Grace?

Which of them has been communicating, over the years, beyond the closed street, and isn’t that what we think writers should be doing? Or is there something else I’m missing here, and, if so, would someone please say what it is?

*

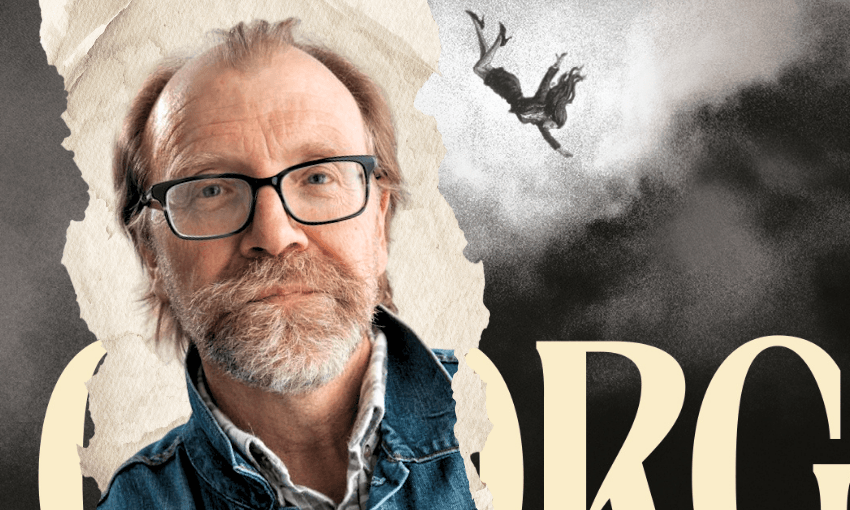

Lacking a local Nobel Laureate in Literature to talk about, I’ve gone ahead and invented one, in my new novel The Back of His Head (VUP, October 2015). This is Raymond Thomas Lawrence (1933-2007), author of Miss Furie’s Treasure Hunt (his first work, a perversion of the Hansel & Gretel myth, in which the children get eaten by whatever it is the witch turns into), Flatland (based on Lawrence’s experiences in the Algerian War of of Independence), The Outer Circle Transport Service (a Kiwi comes of age in Birmingham), Bisque (a young woman travels to Ibiza), and, most famously, Kerr, a version of his own solo trip across the Pacific in a home-made yacht and the novel that is widely agreed to be his finest work. He has ten novels in all and four collections of short stories; two further volumes were published posthumously by his estate.

Lawrence is of that second generation of New Zealand cultural nationalists Janet Frame and James K. Baxter – Shadbolt, too – were born into, the first tranche of our writers to have a sense of inheriting a significant local tradition at the end of the Second World War. Like many of that group he is insecure, sometimes rather self-conscious; at other times, though, he is fecklessly over-self-confident, stumping about where angels fear to tread.

Like some (though not all) of that second New Zealand generation he is, occasionally, a complete and utter prick, even (sometimes) sado-masochistic as well: he claims (apart from anything else) to have tortured and killed a young Berber in the Algerian desert and quite possibly done worse to him in his ongoing, Foucauldian quest for extreme experience.

After all, behind every successful novel, Lawrence claims – borrowing from Robbe-Grillet – lies a crime, something actual and unforgivable that somehow gives the work of art a kind of authenticity, of arising out of something Real (his mistress, who paints the painting of him that gives the novel its title, uses her own bodily excrements in the ‘hectic, potty’ later stages of her life when she edges into dementia and tries, tries, tries to cross that final barrier between Art and Life).

Over the years, a number of writers are known to have been ‘difficult’: White, notoriously, took his frustrations out on his life-partner, Manoly Lascaris; Malcolm Lowry was impossible when drunk and had to be dressed by his wife each morning-after-the-night-before (socks baffled him whether he was sober or drunk); Dickens has recently been revealed as a wife-beater (the composer William Walton, too); Hans Fallada shot a friend, Lawrence Durrell is said to have threatened his wife with a revolver; William Burroughs actually shot his, Louis Althusser strangled his, and so on: a friend of mine once watched one of our more famous writers belabouring his partner about the head with his hand luggage after they’d missed a flight at an airport. Anything to get through that writer’s block, I suppose.

It’s hard, though, to think of any of these as quite of the order of awfulness I’ve given my invented Dead White Male Author: he’s charming, certainly, but in the same way that Albert Speer reported Hitler to be charming. Most of the time he is contemptuous even of the welfare of the nephew he has adopted as his son, who narrates much of the novel and is the chief recipient of his uncle’s torments.

At one point Lawrence tries to write on the nephew’s adolescent neck with the tip of a knife: ‘You’ll never forget me,’ he promises the struggling, snivelling boy – who, in return, worships him – inevitably; Proust talks about this sort of thing – and is forever broken by him, something evident in the spinal scoliosis he develops as he gets older and which increasingly twists him about and bends him over even as he continues to defend the late writer as a genius and a great man. In a sad, provincial echo of Henry James he insists on calling his uncle ‘the Master’.

Why write all this, why bother with a man like this? – well, evviva il coltellino, as Italian audiences used to call out, apparently, whenever the famous castrati hit the high notes three hundred years ago – ‘Long live the little knife,’ in other words, the one that brought this magic about – aware as they were of the same irony in great artistic achievement that obsesses the Master – ‘the killing in it,’ as his nephew says. Art, in this novel, doesn’t come from Above; it comes from the gutters, the sewers, from the everyday places we prefer not to think of as we seek, desperately, to move towards the light. This is a writer who doesn’t need to be walled off from the noisy street: the noisy street needs to be walled off from him, so eager is he to remind us of the primeval ooze from which we all emerged.

How, then, did Raymond Thomas Lawrence become papabile, so to speak? – by putting all that dirty stuff behind him (‘maturing,’ it’s sometimes called) and writing a self-censoring suite of fictions in his middle years in which he does, indeed, and despite himself, turn the reader toward the light. ‘An extraordinary act of empathy,’ is one reviewer’s judgment of his turning-point novel, the Birmingham one, and the reviews get better and better as further novels appear. The Master himself becomes more and more cynical: ‘Drop in Dante and two fucking Shakespeare quotes and suddenly it’s great art,’ he tells his narrating nephew. ‘Suddenly they forget all the buggery and bestiality and cannibalism.’ Eventually, at some point in his journey the raft-tripping Kerr of Kerr realizes that Everything Is Connected – something like that – Australian readers should be thinking of Voss here, English readers of Pincher Martin, and everyone else of The Old Man and the Sea. As soon as Lawrence offers this glimpse into the Meaning of Life and the Perfectibility of the Imperfect, the prizes start to roll in.

Finally, for the Master, the call to Stockholm. ‘We knocked the bastard off,’ he informs his waiting friends after he puts the phone down (displacing, in that figment called the real world, poor Seamus Heaney, falsely rumoured actually to have received the same phone call in 1995, the year in question). ‘I’ve made it,’ Lawrence mutters to the narrating Peter as the celebrations run wild. ‘Now watch what I do. I’m going to fuck it all up.’ He goes back to his old ways, writing a late novel so appalling and unrelenting – at last he tells us what he actually did to the boy in the desert – so unliterary, so uncalled for – that readers and reviewers recoil alike and his reputation is in tatters (peeing on the stage during the opening of the creative writing school that bears his name doesn’t help, of course). Not long afterwards, he blows it up – the school, that is – in an act of penitence for having betrayed his earliest principles, for having been caught up and seduced by the prize-awarding system that dominates global publishing today: for descending to the writing of mere Literature, with all its feckless Hope and Meaning. Just as Major Kong goes down with the bomb at the end of Doctor Strangelove, the Master goes up with his at the end of The Back of His Head.

*

To me as its mere author, The Back of His Head reads like a parable of reading, a book that asks just how much and how little someone else’s writing can be expected to yield the reader. Can art ever go ‘beyond itself,’ or is it doomed always to be like the painting of the back of Raymond Lawrence’s head that names the novel, done by a woman who has spent her life trying to work out what makes him tick but has finally given up and gone round the back, so to speak?

I recall Billy Apple’s imperishable work ‘Used Bathroom Tissue After a Bowel Movement’, which utterly scandalised right-thinking Christchurch when exhibited there fifty years ago: it consisted of exactly what it says on the tin, no painting or drawing involved, just that most lumpen of realities itself: unredeemed, unredeemable poo, offset by a bonbon of twisted toilet paper artfully arranged. Offered in what just has to be called a po-faced manner, this work of art (well, the mounting was nice) represented the logical end-point of realism: ‘Is this what you meant, then?’ is the question it asks. But if the answer is ‘No,’ then we have to accept that art, from that point, progressively backs off and starts telling lies. It’s all that’s left for it to do.

The inevitable corollary, then: can art change anything (our greatest dream), can it make things happen out there in the world? Not according to Raymond Thomas Lawrence. For him, it has no real social function, after all, a belief that cuts against much that we assume prizes recognize and much that is implicit in the humanist’s belief in our perfectibility. ‘For his holding before our collective gaze the wretched of the earth,’ says his Nobel citation: for reminding us that the poor are always with us, I suppose, a fact that hasn’t actually changed since Matthew’s gospel told us of it early in the first millennium.

Actual Nobel citations given over the years, as we’ve seen, are no less idealistic, but are they anything more than expressions of hope that the rain might one day end and our washing be put out at last to dry? And if they’re not anything more than this, and if no other such prize is for anything better, why are these prizes still handed out? What are they rewarding; and what is it that they’re writing, those writers in their sealed-off streets real or figurative, if not Wilde’s ‘ugly things for the poor’ – things to be read by other residents in the same street to make them feel better about where they live?

‘No entry to all vehicles, writer at work.’

The Back of his Head by Patrick Evans (Victoria University Press, $30) is available at Unity Books.