Which books made the final 16? With commentary by books editor Claire Mabey.

From 175, to 43, to the final 16. Publishing is brutal. Awards are a necessary and propulsive part of the industry: recognising excellence and giving the market a boost. This is the stage of the awards cycle where I start to imagine the backroom argy-bargy: circles of judges sucking on cigars, slinging quips, slurping on whiskeys late into the night as they haggle and argue the merits and flaws of each title while clouds of acrid smoke fill a windowless room. Maybe someone starts muttering insults, maybe another storms off, leaving their counterparts glancing at their wristwatches before dropping their heads into their hands wondering how they’ll ever come to a consensus.

But they did. And as the sun rises so too does the results of their deliberations.

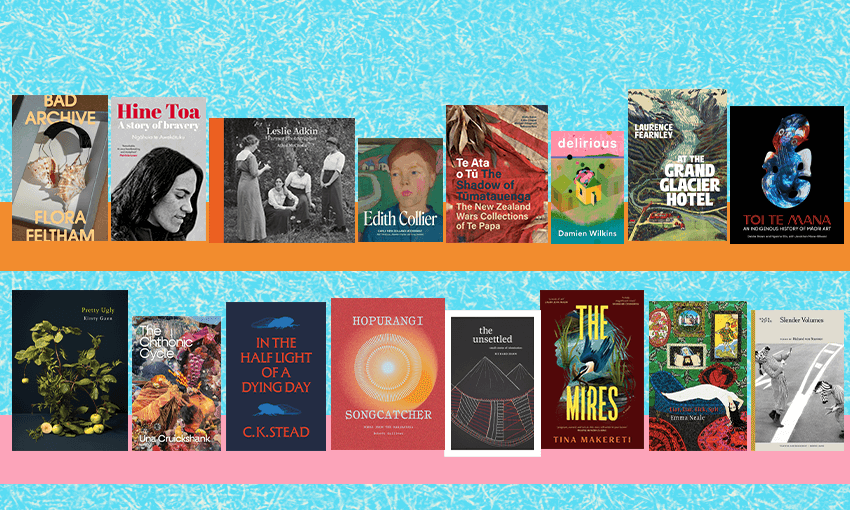

Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction ($65,000 prize)

At the Grand Glacier Hotel by Laurence Fearnley (Penguin, Penguin Random House)

Delirious by Damien Wilkins (Te Herenga Waka University Press)

Pretty Ugly by Kirsty Gunn (Otago University Press)

The Mires by Tina Makereti (Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Rangatahi-Matakore, Pākehā) (Ultimo Press)

Thoughts: This is not the shortlist I was expecting. But at the same time I’m neither surprised nor disappointed, much. I’m bummed that Ash by Louise Wallace didn’t make the cut. It’s a terrific, inventive, truthful, biting book: rare, short and refined. I’m also surprised that Amma by Saraid de Silva didn’t make it: widely championed, loved by readers, with rich, revelatory characters. De Silva can be consoled by the fact that Amma was just announced on the longlist for the Women’s Prize alongside Miranda July, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Elizabeth Strout and Kaliane Bradley among others – a major achievement.

What we have here are four senior and award-winning authors: Laurence Fearnley won the fiction prize in 2011 for The Hut Builder; Kirsty Gunn won the book of the year in 2013 for her novel The Big Music; Damien Wilkins won the fiction award for The Miserables in 1994; and Tina Makereti won the 2016 Commonwealth Writers Short Story Prize.

Laurence Fearnley is a reliably excellent novelist: she is a master at evoking the ways bodies and minds exist in specific environments. At the Grand Glacier Hotel is the third novel in her project of writing a novel for each of the five senses. This one, according to Fearnley, aligns with sound. However for me it wasn’t the noise of the novel (set in a remote hotel surrounded by bush) as much as the physicality of the main character who is recovering from major surgery to remove a cancer. The images that linger are of a woman learning to move a changed body in the world: from taking a bath, to encountering strangers, to bush bashing. In many ways it’s a quiet novel, unsettling even as it heals. The shortlising will, I hope, turn more people onto Fearnley’s work and her extensive backlist of novels set in the wilds of Aotearoa.

Delirious by Damien Wilkins is the one I’m picking for the win. Wilkins draws such detail, from the mundane to the extraordinary, from his characters that it’s hard to believe it’s fiction. That’s what you want in a novel: to be fully absorbed into another world and invested in the comedies and tragedies of other lives. Gabi Lardies and I discussed Delirious and both concluded it is superb.

Otago University Press’s decision to launch a series of short story collections has paid off with Kirsty Gunn’s Pretty Ugly. Gunn (who lives in Scotland and is a professor of creative writing in Dundee) is widely known for her heartbreaking short novel, Rain (1994); and The Big Music (2012). She is an award-winning short story writer and is known for a style that tests the reader, that is interested in the line between fictional and the real, and plays with ideas of artifice and arrangement. The short story is notoriously difficult to do well. Airini Beautrais won the fiction prize in 2021 for her collection Bug Week. Maybe we’ll see the form rise to the top once again.

Tina Makereti is a masterful writer. I’m always at ease in her prose and provoked by the ideas in her work. The Mires is a novel for our times: it’s about mindsets, how people are pitted against people thanks to how they are steered to think and why. Holding the fragile web of relationships is the land underneath, the waters, that in this time of climate crisis present a vast tension and a mighty force.

Four books by experienced, award-winning writers. International judge Georgina Godwin has been enlisted to offer an external eye and help our local judges pluck out a winner. Godwin is books editor for Monocle Radio and the host of the flagship literary show Meet the Writers, and current affairs programme The Globalist. She has previously judged the Bailie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction, The Caine Prize for African Writing and the British Book Awards.

Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry ($12,000 prize)

Hopurangi – Songcatcher: Poems from the Maramataka by Robert Sullivan (Ngāpuhi, Kāi Tahu) (Auckland University Press)

In the Half Light of a Dying Day by C.K. Stead (Auckland University Press)

Liar, Liar, Lick, Spit by Emma Neale (Otago University Press)

Slender Volumes by Richard von Sturmer (Spoor Books)

Thoughts: “True poets know that institutional gratification is ultimately meaningless, and true success can only be found in the withholding gaze of the distant and unforgiving moon,” said Hera Lindsay Bird, The Spinoff’s poetry editor, in her commentary on the longlist. Nevertheless we have four collections from four writers and three publishers (Auckland University Press continuing a long list of excellent poetry publishing) from which to pick one to crown as poetry ruler of the year.

I loved Slender Volumes by Richard von Sturmer, published by new indie press Spoor Books, who promise great things for our local scene. Emma Neale is a poet who can wield that kind of mind-bending magic that only the best poets seem to have access to. Stead of course is no stranger to winning awards: he’s won the poetry prize in its various iterations twice before, and scooped other awards alongside. Robert Sullivan is also celebrated poet with shortlistings and wins accompanying severals of his works.

Poetry is surely one of the most subjective forms to appraise. Convener of judges for the poetry prize, David Eggleton, intimated that it was a hell of a time choosing the final four: “We sought to argue, debate and rationalise — and eventually harmonise — our choices; pitting militant language poets against equally militant identity poets, spiritual poets, polemical poets, experimental poets and careful traditionalists in pursuit of acknowledging books of literary excellence at the highest level.”

The top four here are all winners to me but for the institutional crown I’ll stick my pin in Slender Volumes.

Bookhub Award for Illustrated Non-Fiction ($12,000 prize)

Edith Collier: Early New Zealand Modernist by Jill Trevelyan, Jennifer Taylor and Greg Donson (Massey University Press)

Leslie Adkin: Farmer Photographer by Athol McCredie (Te Papa Press)

Te Ata o Tū The Shadow of Tūmatauenga: The New Zealand Wars Collections of Te Papa by Matiu Baker (Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Te Āti Awa, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Whakaue), Katie Cooper, Michael Fitzgerald and Rebecca Rice (Te Papa Press)

Toi Te Mana: An Indigenous History of Māori Art by Deidre Brown (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu) and Ngarino Ellis (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Porou) with Jonathan Mane-Wheoki (Ngāpuhi, Te Aupōuri, Ngāti Kurī) (Auckland University Press)

Thoughts: First, a note on BookHub. It’s a website that pulls together indie bookshops from all over the country. You go there, you type in the book you’re after, you buy it from the shop that has it. BookHub means you get to interact with booksellers all over Aotearoa – I use it all the time and love how each bookshop has a different manner: some send notes of gratitude with your shopping, others send emails saying how excited they are for you to read what you’ve ordered, there can be postcards and lovely, scented wrapping.

Second, this list of finalists includes four senior curators at Te Papa as history and art dominates the shortlist: Athol McCredie (Leslie Adkin: Farmer Photographer); and Matiu Baker, Katie Cooper, Rebecca Rice and museum research associate Michael Fitgerald (Te Ata o Tū The Shadow of Tūmatauenga: The New Zealand Wars Collections of Te Papa). So sweet when your job includes book writing and publishing.

Jill Trevelyan won this prize in 2009 for her outstanding biography of Rita Angus. The book she’s back again for (with co-authors Jennifer Taylor and Greg Donson), Edith Collier: Early New Zealand Modernist, is a revelation: there are 150 colour reproductions of Collier’s paintings and multiple contributors responding to them. Collier was ahead of her time, a student of Frances Hodgkins, a painter from Whanganui finally finding acclaim through this publication and its accompanying exhibition at the newly reopened Sarjeant gallery. Big book, important book, has award-winning written all over it.

Academics and authors Deirdre Brown, Ngarino Ellis and the late Jonathan Mane-Wheoki wrote about how they approached the epic Toi Te Mana: An Indigenous History of Māori Art for The Spinoff last year. It’s a huge publication in both scale and significance, no doubt transforming future studies of art history in Aotearoa and the world. It’s the book to beat though I’ll always have a soft spot for Leslie Adkin: Farmer Photographer and its mesmerising, haunting black and whites.

General Non-Fiction Award ($12,000 prize)

Bad Archive by Flora Feltham (Te Herenga Waka University Press)*

Hine Toa: A Story of Bravery by Ngāhuia te Awekōtuku (Te Arawa, Tūhoe, Ngāpuhi, Waikato) (HarperCollins Publishers Aotearoa New Zealand)

The Chthonic Cycle by Una Cruickshank (Te Herenga Waka University Press)*

The Unsettled: Small Stories of Colonisation by Richard Shaw (Massey University Press)

Thoughts: Herewith are four books of creative non-fiction! There’s no muddling of genre here in this category where the highly academic can mingle with the determinedly personal. Authorial voice powers these four, brilliant books: from Ngāhuia te Awekōtuku’s powerhouse memoir, to unique debut essay collections from Flora Feltham and Una Cruickshank, to Richard Shaw‘s valuable work dispelling settler mythologies.

Genuinely no clue which book will win out. I’ve read them all and loved them all for very different reasons. Richard Shaw’s work, I think, is essential for Pākehā in such times as we are in (and I’ve seen first hand how important for Māori, too). Flora Feltham does that thing where the hard and the soft come together in one perfectly formed piece of observation and probing: the essays are affecting, curious, wide-ranging. Cruickshank has offered our bookshelves something entirely unique – a glittering necklace of gems to turn over one by one. But I think the award will go to te Awekōtuku’s autobiography (reviewed in rapturous terms on The Spinoff by Matariki Williams). Autobiography is hard to write well – to convey the origins and the underneath – and te Awekōtuku not only has the material to weave, but the style.

Kudos to the judges:

Thom Conroy (convenor); bookshop owner and reviewer Carole Beu; and author, educator and writing mentor Tania Roxborogh (Ngāti Porou) (Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction); poet, critic and writer David Eggleton (convenor); poet, novelist and short story writer Elizabeth Smither MNZM; and writer and editor Jordan Tricklebank (Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Mahuta) (Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry); former Alexander Turnbull chief librarian and author Chris Szekely (convenor); arts advocate Jessica Palalagi; and historian and social history curator Kirstie Ross (BookHub Award for Illustrated Non-Fiction); author, writer and facilitator Holly Walker (convenor); author, editor and historical researcher Ross Calman (Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāi Tahu); and communications professional, writer and editor Gilbert Wong (General Non-Fiction Award).

All of the above books can be ordered through Unity Books. The winners (including winners of the best first book awards) will be announced at a public event at Auckland Writers Festival on May 14.