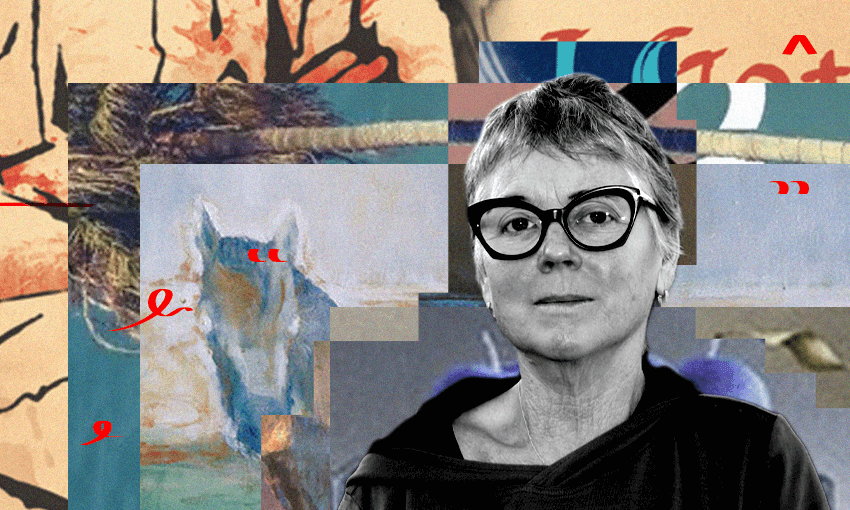

Welcome to The Spinoff Books Confessional, in which we get to know the reading habits of Aotearoa writers, and guests. This week: Laurence Fearnley, author of At the Grand Glacier Hotel.

The book I wish I’d written

Sue Wootton’s The Yield. When I read Sue’s poems, I am aware of their depth, that there is meaning to be gained, to fathom. A lot of this is down to craft. Every line, line break, word, syllable, punctuation mark is considered and, as a result, every poem works on an intellectual and primal level.

Everyone should read

Carl Nixon’s The Waters. I admire Carl’s ability to capture suburban Christchurch and South Brighton so perfectly. Every scene nails it in terms of the setting and the characters, as well as the time period. He’s a terrific writer – especially in terms of capturing the South Island.

The book I want to be buried with

I’d quite like a blank notebook and a stick of charcoal, to capture the peaceful blackness of my surroundings. Massey University’s Guide to New Zealand Soil Invertebrates (available online) would also be really interesting in that situation. I like the idea of natural burials, shallow graves, and becoming part of the earth. It would be nice to be surrounded by insects and tree roots, to feel their company in the dark.

The first book I remember reading by myself

Not the first book, but, rather, the first book I fell in love with. The Fiat Book of Birds 1 – Common Birds in New Zealand: Town, Pasture and Freshwater Birds by Janet Marshall (Paintings), F.C. Kinsky and C. J. R. Robertson. I had all three books in the series but I loved this book the most because it featured all the birds I might see in my local environment, many of them introduced. The book is small, spiral bound with a strange textured plastic cover that features a Welcome Swallow.

Dystopia or Utopia

Samuel Butler, Erewhon.

Fiction or nonfiction

The only books I don’t tend to read are graphic novels and comics. I seem to have a problem when words and pictures interact too closely. My brain doesn’t know whether to read or look. I can’t read when music is playing in the background, either. I recently finished Alison Ballance’s Takahē which describes the natural and cultural history of the bird. Alison undertakes years of research and yet is a storyteller at heart, and her books are lively as a result.

It’s a crime against language to

I always liked using “amongst”, for the sound and also because it seems like a slightly hesitant word compared to “among”. It’s softer: amongst the trees/ among the trees. “Amongst” is a word that cradles the reader.

The book that haunts me

A beautiful story by Lawrence Patchett called ‘The Road to Tokomairiro’ from his book I Got His Blood On Me. On the surface, Lawrence’s writing has a rugged, frontier, quality, but underneath, holding it all together, is a delicate web, almost fragile in its nature. So, you get these beautiful contrasts between the exterior and internal worlds, the natural environment and the souls who inhabit it. There is a rawness on the page that is underscored by rich emotional intelligence, which enables him to capture love and loss. A great story and a wonderful collection. Every time I travel through Milton and Lawrence I “see” this story. I really hope he writes and publishes another novel soon.

The book that made me cry

Nelson poet Rachel Bush’s Thought Horses is very moving. The collection was published shortly after her death in 2016. She has an incredible clarity when it comes to observation which somehow (magically) illuminates meandering thought. I don’t understand how she does it. Many writers would treat these two aspects as “opposites”, but they’re not. Brilliant.

Encounter with an author

Professor Emeritus of Geography and biogeographer Peter Holland (1939-2019) — author of Home in the Howling Wilderness: Settlers and the environment in southern New Zealand — was someone I got to know when I was doing research in the Hocken library. He used to sit at the table with an enormous, heavy, leather-bound ledger opened in front of him, combing through accounts and sales entries to add to his knowledge of settler-farmers. He’d look at when, where and how they spent their money: land, livestock, crops, sundries … meticulous research. I didn’t know him well but I loved talking to him; he was very sharp but funny, warm and modest. One conversation we had concerned scent, and he described his childhood in Waimate and his love of the smell of ryegrass, which he remembered from his time working in the paddocks near Hakataramea.

Greatest New Zealand book

David Eggleton says it best in ‘The Great New Zealand Novel’ from his Poet Laureate collection Respirator. He offers a postscript with ‘Old School Prize’ from the same collection. I first read David when I was just out of university, and ‘Futurist’ felt like the poem of my generation. It had a kind of explosive energy, it thrummed to the beat and everybody joined in on the chorus. Respirator keeps that energy going but there is a softer, wiser thread that comes to the surface. “…there are showers of clattering sequins…” from the poem ‘The Mackenzie Basin’. My “best book” of 2023.

Best place to read

Alone, in a parked car.

At the Grand Glacier Hotel ($37, Penguin NZ) is available to purchase from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.