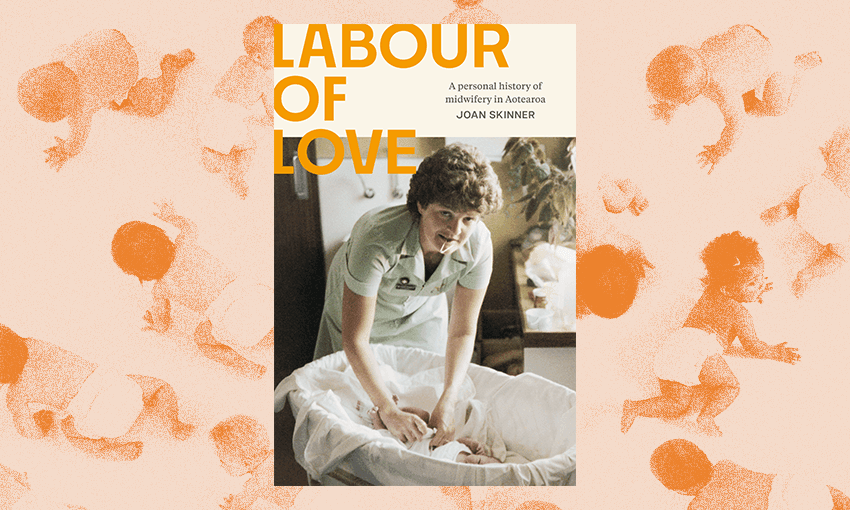

Joan Skinner’s first book, Labour of Love, is a chronicle of more than four decades of midwifery. She’s determined that the profession belongs just as much to the future as to the past and present.

The beginning of Labour of Love works perfectly. Joan Skinner, a midwife and academic who has made a late-in-life pivot to creative writing, describes the first birth she saw as a trainee midwife. The woman has little to no agency. The setting is a sterile hospital. Skinner, just returned from a year living in Tonga, is terrified.

Then she turns to the last birth she plans to be part of: her grandchild, her daughter having a gentle homebirth, lights low, birthing pool, intense and raw and human, members of the family present and involved.

In some ways, Labour of Love (great title) is an attempt to chart the path between the 1960s model of birth in New Zealand and the current model: still often in medical settings, but with partners and family members more involved. To do so, Skinner intersperses the broader narrative of midwifery in New Zealand with stories from her own experiences.

The daughter of an obstetrician, Skinner grew up in a Catholic family in Wellington with a father who was always, always being called away to attend other people’s births. A shadow hung over her childhood: her mother had carried 10 babies to term; five had died of a blood disorder now easily treatable. Wanting to do hands-on work, Skinner trained to become a midwife.

The book is split into roughly three parts. After describing her education, a model where doctors – not people giving birth or midwives – were the authority in the room, she enters work as a midwife as dedicated maternity hospitals close and births are made part of the main hospital system. While Skinner starts having her own babies, she begins to wonder how safety and risk are managed during births.

Through the 1970s and 80s, she becomes involved in the movement for home births to be seen as normal and natural, for models of power to shift. What is a safe birth? Hospitals and stirrups, forceps and high beds, heart monitors and ultrasounds: who do these make feel safe? Birth, as she points out, is a part of life that is about life, is normal and expected, so why is it so often treated in the same way as an illness?

These questions are profoundly relevant. After all, everyone has a direct experience of pregnancy and birth, even if many of us don’t remember it. They also lay the groundwork for the next section, where Skinner starts to contemplate bigger, structural questions. After being involved in separating midwifery and nursing as professions, from political and academic sides, Skinner’s focus shifts. She’s laid the groundwork well; the structure here is immaculate. Skinner brings the reader along with her as she questions the ways in which poverty and racism affect birth and how those factors might be applied to bigger picture work. These questions lead Skinner to start working internationally.

There’s an element of innocence to Skinner’s sidle to international contract work, going to Cambodia and Afghanistan to try to design posters and training programmes to help midwives learn. She’s deeply earnest about it, and by this point in the book, the reader sees why this work matters too. The situations are difficult, the problems are often political, not something that even the best workshops and evaluated outcomes can fix. But wherever Skinner goes there are people giving birth, and there are midwives, usually women, who want this experience to be safe and healthy.

Along the way she charts her personal life. The first chapter, about her early life in Wellington, opens a window on a period of time I didn’t know much about. A few key images were beautifully drawn: the emotion of arriving on a remote island in Tonga to live with a family there for a year; the feeling of peering out the window at people getting married in the Old St Paul’s church in Wellington. Then come her three children, her divorce from her first husband and marriage to her second – it’s interesting, in the way that a generous depiction of someone else’s family always feels interesting. In the final part of the book, Skinner transitions to the role of an academic and a grandmother. I found her description of accepting her ageing body after a stroke startling: “My body’s understanding of itself in space and time evaporated and I slid, fully conscious, to the ground.”

At times I really felt the absence of an index, or at least a “Further Reading” or references list at the end. Skinner’s writing is clear, accessible – she’s a former academic, practised in communicating big picture ideas to the public – but the deviations to her personal life sometimes worked to dilute this. I wanted to tell her that I wanted more of the movements of midwifery, that jumping into the personal wasn’t always needed. I could almost hear the voices of her editors, or International Institute of Modern Letters classmates, asking her to be more personal and revealing.

The focus on personal history (what does that mean, anyway?) also meant that there were some missed points. With Skinner’s global travels, I thought that it would have been worth spending some time, even just a few pages, on a more thorough history of midwifery, as a means to link the disparate practices that Skinner encounters, and understand how the medical model emerged by the time she was being trained in the 1970s. She refers to the meaning of midwife repeatedly – “with woman” which focuses on the person giving birth – but doesn’t dwell on the origins, or consider the kinds of working conditions that early European midwives might have encountered.

Nor does she spend much time talking about Māori midwives or pregnancy practices, or even refer to where an interested reader could learn more about this. Perhaps the personal angle was a way to focus this history of midwifery on the areas Skinner had experience of; as a reader with limited knowledge of this area, I would have liked more moments of acknowledging the gaps.

In Skinner’s overseas work, she repeatedly refers to fraught territory. “It’s complex,” she says. To have a life’s work in Aotearoa advocating for it to be easier to give birth safely at home, without medical intervention, then go to another country and ask for more medical interventions; glimpses of glistening plastic birthing beds in medical centres far from people’s homes. To realise that she can’t save an unconscious baby from a family where the woman is not free to go to a doctor, or that the charade of the North Korean government means there is no way to tell if midwife training is taking place at all.

I appreciate these complexities, especially since Skinner is dealing with the gnarly bureaucracy of acronymed UN organisations and their power and funding methods. However, while non-fiction can’t offer tidy resolutions to such complexities, I would have liked to have seen some of Skinner’s thinking through different models and solutions – after all, she’s hardly the first person to encounter spaces of inequality in healthcare. Paul Farmer’s work on global liberation and health would have been an obvious reference, for instance. That said, her compassion and curiosity about other people’s ways of doing things and her respect for the local healthcare practitioners is evident. I think her way of describing these situations would particularly open up readers who don’t have much cause to think about global healthcare in their lives.

Throughout Labour of Love, Skinner is open to change. She wants midwifery to change too, to incorporate mātauranga and more expansive ideas of gender to make giving birth safer and less medicalised. The book is just one person’s glimpse of the history of Aotearoa midwifery, and as Skinner indicates, the profession is facing difficult headwinds throughout the country. But people are going to keep giving birth, and the opportunity to think about the future is welcome.

Labour of Love by Joan Skinner (Massey University Press, $40) can be purchased from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.